Every day conscientious consumers of news are bombarded with images of melting ice caps, islands of ocean plastic and species that are becoming increasingly endangered. We read data confirming that nations around the world are falling short of emissions targets set in the United Nations Paris Agreement and that we are consuming more natural resources than the world can produce.

It’s a bleak picture, one that’s all too real.

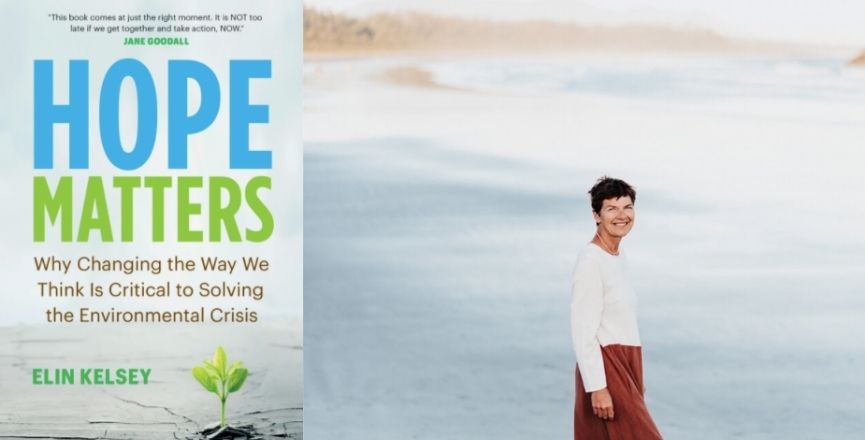

But zoom out and you’ll see hope abound, says Victoria-based author and environment expert Elin Kelsey in her new book Hope Matters: Why Changing the Way We Think is Critical to Solving the Environmental Crisis.

In Hope Matters, Kelsey argues that a hopeful approach to activism, rather than relying on pervasive doom-and-gloom environmental narratives, will help to push the movement for a greener world forward more than despair ever could.

“People are really hungry for hope,” Kelsey says in an interview with rabble. “I think hope is a collective action and it’s very important when we’re dealing with these bigger issues.”

Today, there are more square kilometres covered by designated marine protected areas than ever before, countries around the world are implementing bans on single-use plastics, and people are adopting plant-based diets and low-emission lifestyles at a rapid rate.

Meanwhile in nature, plants and animals are naturally repopulating in areas once barren, such as the thriving (yet radioactive) grey wolf population in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, an example Kelsey highlights in a chapter of the book called “Stories Change.” Ecologists estimate that the population in the CEZ is seven times higher than surrounding reserves.

Surveys continue to show that climate change ranks as the top issue for Canadians. Climate change awareness is at an all time high, a telling fact that Kelsey uses to argue that all it takes is a hopeful mindset to shift this momentum to greater positive action.

“Environmental situations are not all bad or all good; they demand nuanced understanding,” she writes in Hope Matters. A wider perspective and balance is required to get the full picture.

Kelsey first became interested in the idea of hope in the context of environmental activism while leading children’s workshops with the UN Environment Programme in 2008. She met kids aged 10 to 14 from 92 different countries who felt angry, hopeless and feared that they had no future.

All they had ever heard was catastrophic environmental messaging, while observing that many of the adults around them were unwilling to make changes to ensure long-term survival. They were left frozen with despair, believing that there is ultimately no solution.

This broke Kelsey’s heart. She worried that exposing children to predominantly negative environmental news would hurt both their mental health and the cause in the end.

This is what Yale climate change communications expert Anthony Leiserowitz calls a “hope gap” — people are very aware of the wide-reaching problem but they feel powerless because they aren’t exposed to solutions.

According to the American Psychological Association, climate change can bring on stress, depression and PTSD, while putting strain on interpersonal relationships and leading to a rise in aggression, violence and crime.

It is true that fear or anger can serve as motivating emotions. However, Kelsey argues that the negative impact on mental health can create barriers to solutions. These emotions may help to mobilize, but they can also snuff out momentum as activists succumb to burnout.

Simply put, fear alone doesn’t work.

“We have massive, terrifying, urgent environmental problems. But we also have powerful successes that we need to amplify above the din of hopelessness,” she writes in Hope Matters.

This doesn’t mean activists should hold a Pollyanna view of the world or be complacent. In fact, the opposite is true, Kelsey says. Being armed with recent, up-to-date facts and following up on solutions helps to “guard against cynicism.” It’s called “evidence-based hope.”

“When we can see evidence that our actions are shifting things, it’s very empowering and it’s much more likely to give us the resilience to stick with hard work — and we have a lot of hard work to do,” she told rabble.

The problem is, most news outlets and scientific studies exist to identify problems as they arise. This can be helpful to alert people to previously-unknown issues. But the 24-hour news cycle means that stories about solutions get left to the cutting room floor.

“We are inundated with more bad news about the world than at any other time in history,” Kelsey says. “We know that only hearing about what you’re doing wrong is very disengaging and it’s defeating.”

“We don’t want to be flogging people at the very time they care the most.”

Despite the overarching narrative of doom and gloom, Kelsey says the news is not all bad.

Like many other things in life, the state of the environment is not black and white, regardless of how often it may be portrayed that way. Kelsey suggests activists find comfort and hope in the grey zone in between.

“I think we need to get more comfortable with ambiguity,” she told rabble. “These things can be highly broken and these things are moving in a positive trajectory. Both of those things are true.”

“It behooves us to keep track of time and changes over time,” Kelsey says. “It both emboldens us and it helps us to put the pressure where we need to put the pressure, rather than generalized statements that something is broken.”

In a search for positive solutions and inspiration, Kelsey began to ask environmental scientists: “What makes you hopeful?”

It didn’t take long for experts to list victories large and small: from forests regenerating faster after an eruption at Mount St. Helens, the resurgence of great white sharks along the California coast, to bleached corals and other marine life in the Great Barrier Reef adapting to warmer waters in just a few years.

“We worry about complacency around hope but we should be worrying about apathy and disengagement around doom and gloom,” Kelsey told rabble.

For many scientists she spoke to, no one had ever asked them that question. And it was their hopeful answers that kept them motivated despite challenges.

“Hope is not complacent,” Kelsey writes in her new book. “It is a powerful political act.”

Lauren Scott is an arts and environment journalist based in Hamilton, Ontario.

Author image: Agathe Bernard