Capitalism’s been giving itself some extremely bad press lately. Finance capital’s approval ratings (if any were taken on a regular basis) have to be at as low a level as at any other time in the last hundred years.

Even the mainstream business press seems at a loss to justify the new mantra of austerity in any way that makes sense. The ‘shock doctrine’ as applied to the current historical moment has meant yet another tired strategy of attacking the welfare state and privatizing everything, while unemployment skyrockets and life becomes more tenuous for everyone, even in the richer northern states (everyone but the 1 per cent, of course).

The solutions proferred by status quo neoliberal thinking are obviously not up to the task of fixing a badly broken economic system. What can we do about this? How did we get here?

Ironically, during the years of the Keynesian consensus of high public investment and a ‘tripartite compromise’ between business, labour and the state, neoliberal thinkers like Milton Friedman and Friedrich Hayek were still viewed as absurd preachers of an economic ideology made irrelevant by the failures of laissez-faire imperialisms of the pre- and interwar periods in the first half of the twentieth century.

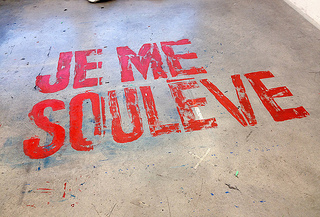

The power of revolutionary ideas

Of course, it’s worth asking why Canada (and much of the richer, northern world) enjoyed the ‘tripartite compromise’ with relatively high standards of living. In reality, the power of revolutionary ideas shifted the postwar consensus and created space for Keynesian ideas.

The enduring irony of the current phase of capitalist crisis is that reformist tinkering at the edges of crises is actually naive, and deep-seated change is practical. As an old Irish adage puts it: everything in moderation, including moderation. To proffer more radical ideas, however, you need two things: i) active, organized revolutionaries, and ii) opportune historical conditions.

Put in Canadian historical terms, the precursors to Tommy Douglas were reds (please google the following names) like Ginger Goodwin, Annie Buller, and others pushing the envelope in (among other things) the Winnipeg General Strike (1919), the Bienfait Saskatchewan miners strike (1931), the On to Ottawa Trek (1935), and the early union organizing drives in the 1940s and 1950s. All of these things raised the expectations for better public policy (health care, unemployment insurance, pensions), but it was radicals who got the ball rolling (while social democrats, by in large, got the credit, though Douglas is a unique person in the social democratic camp).

Things went decidedly sour as the ‘tripartite compromise’ took root in the 40s and 50s with the anti-communist witch-hunt and Stalinist direction of the socialist left, but this record doesn’t discount the momentum revolutionary ideas created. This period of fratricide did, however, have the Canadian consequence of pitting the commies against the CCF (with bad behaviour on both sides), and turned many against the notion of socialism in general, an antipathy which is still arguably with us.

In 2012, we find ourselves not at the opposite side of the scale relative to the time of Keynesian consensus but somewhere closer toward it. The social democratic vision that Canada realized with the creation of a strong, publicly funded and universally accessible health system, along with other forms of social security in public pensions and attempts to create an accessible postsecondary education system, were all innovations of a more confident time, one not yet buoyed and buffeted by multiple oil shocks and financial crises that were to pit corporations and notably the finance sector against the state and its social democratic tilt.

Neoliberalism takes its toll

Banks were largely successful at coaxing (or buying) governments throughout the 80s and 90s to let the logic of ‘deregulation’ and ‘liberalization’ take hold, despite multiple and deepening financial crises. As banks were allowed to hold less and less reserves to set against their lending and investment activities, more and more arcane forms of speculation de-linked from the productive economic sphere began to take root, leading to complex and unstable schemes like fixing international rates (e.g., LIBOR), currency speculation, derivatives and securitized mortgages, credit default swaps and vulture funds (all enormously profitable for banks, hedges, and investment firms, their owners and investors).

Another profitable result (for banks and other holders of government debt) of moves to loosen restrictions on banks has been the movement to so-called ‘quantitative easing’, a nice little racket whereby governments buy back their debt from private holders. In the current dysfunctional capitalist toolkit for managing the chaos resulting from finance capital’s increasingly arcane methods of enriching its protagonists, buying back debt from capitalists remains one of the only tools of monetary policy left to governments, with interest rates at near-zero or zero levels.

Of course this narrow range of government action with respect to monetary policy is exactly the kind of limited scope that the neoliberals, ridiculed and ostracized in an earlier age, want when it comes to government action in a capitalist system. The challenge of the current moment is to broaden our scope and increase our range of action in coming to grips with capitalism’s age of permanent crisis.

Finance capital, as always, operates in its own interest, or principally, in the interest of those who profit from a system of near-zero accountability. Our challenge is to imagine a financial system that works to benefit people and planet first, rather than the 1 per cent first model we have in clumsy and destructive operation now. As such, even moving to increase regulatory restrictions on banks, whether in terms of requiring they hold more reserves or not, for instance, is merely one reformist step into reclaiming ground lost to the neoliberals during their long predominance in economic policy and ideology since the late 1970s and their first political prophets (Thatcher and Reagan, notably).

Getting out of capitalist crisis

More than chipping at the edges of finance capital, we need to keep up the pressure as social movements and citizens on left political parties — and everywhere that we can — to advocate for alternatives that move away from 1 per cent solutions.

We have let the juggernaut of finance capital dictate terms through pliant governments for too long already, and have forgotten the positive example set after World War Two, when it was far more obvious that letting the 1 per cent steer our economies would comprise a road to ruin that was to be avoided at all costs. We have let our hard-won historical lessons slip away in the last forty years, and now we are paying the price for becoming comfortable and allowing the 1 per cent to shape policy and construct a world that has seen its own ranks grow their wealth precipitously, while the rest of us lose more control over our economic destinies.

Measures like a financial transactions tax (the ‘Robin Hood Tax’), now gaining support in a Euro zone racked by capitalist financial crisis, are long overdue and would only chip at the edges of a solution, by raising substantial funds that could be used to bail out private finance capital’s mistakes.

Taking lessons from midcentury pioneers, the world needs a return to ‘planned economies’ that could steer us away from increasing inequality and ecological catastophe. What if we required preferential lending and investment in people and planet – in productive green economies and communities, instead of tolerating a global financial system dominated by speculation, hedging and ‘vulture economics’?

What if we required production and investment to serve communities and people, rather than letting finance capital continue disastrous dependency economics through debt in the global South? Such alternatives represent the difference between attempts to harness finance capital through fairer and stricter tax regimes, and collective planning to steer investment to serve the common good.

This sounds revolutionary, and that’s because it is. But whether you apply the term revolution to it or not, economic planning made sense then, and it does now. Surely the world has seen enough of ‘laissez faire’ solutions when it comes to leaving the finance sector alone to wreak havoc on economies. Bringing these arguments to bear in societies pervaded by Friedmanite discourses is a distinct challenge, but one which needs to be met if we’re to work our way out of capitalism’s permanent crisis.

Adam Davidson-Harden and Joel D. Harden are dads fomenting revolution while co-raising young kids. They are devotees of bottom-up politics, and envision a world where the price of oil matters less than our unrealized dreams.