Of all the stars set to descend on Vancouver for the Times Of India Film Awards (TOIFA) on April 4-6, 2013, the arrival of none is anticipated more eagerly than that of Shah Rukh Khan, the reigning superstar of Indian cinema.

As many media scholars have argued, popular Indian cinema — also known as Bollywood — has historically been critical to the making of a national identity, language and culture in postcolonial India. As such, this cinema has played a powerful role in developing notions of national (capitalist) interests and in reproducing the social relations of gender, caste, class and religion (in largely patriotic, if not outright jingoistic, manner). Certainly a number of distinguished directors and stars have sought to develop a cinema of social responsibility; far too often, however, their vision of a democratic and just society has remained marginal, unable to shift popular culture too far from centre left, and even then only periodically.

The severe limitations of nationalist aspirations became evident in the rise of separatist, left, feminist, anti-caste and other social movements in independent India, as well as with the subsequent neo-liberalization of the economy in the closing decades of the 20th century. Moreover, the implosion of the Nehruvian state enabled extremist Hindutva forces to make major advances into the centre of national political life.

With these seismic shifts, Bollywood has become increasingly draped in the hues of an unbridled consumerism and an aggressively Hinduized religio-cultural politics. This is the context in which Shah Rukh Khan has made a name for himself as a Bollywood actor.

Cast early in a psychological thriller as a deranged psychopath who stalks the heroine he loves (Darr), Khan made enough of a mark in the role for leading film directors and mainstream audiences to pay attention to him. A meteoric rise to fame in the film industry followed (he had previously worked in television) and Khan quickly became a household name in India and across Asia (including its various diasporas), as well as in the Middle East and Africa. His popularity continued to grow as his roles shifted to cater to the increasingly urbane, transnational and cosmopolitan South Asian audiences in the West; the enhanced social status and increased political clout of these communities made them an important constituency in the rapidly globalizing order of the 1990s.

Khan’s success was initially based on his casting in the role of the quintessential Bollywood romantic hero. Among his fans, he was loved by mothers as the exemplary son — and son-in-law — they wished for (Karan Arjun, Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge) and by younger women as the deeply sensual and sensitive lover they yearned for (Dilwale, Dil to Pagal Hai, Pardes, Paheli); he also became the beloved of children as the fun-loving father with a boundless zest for life (Kuch Kuch).

If those were the only roles Khan had stuck with in his career, he could have comfortably continued in the trend set by previous Bollywood male superstars and done little more than provide a new model for the heroic trans/national masculinity demanded by the changing socio-economic landscape of India within the context of larger global transformations. But Khan soon began taking on riskier roles, all of which have helped turn him into an institution unto himself.

I started paying attention to Khan when I saw him in Dil Se, directed by Mani Ratnam. The film took the figure of the female suicide bomber and turned her into a heroic symbol of the oppressed minorities fighting the terror waged on them by the Indian state. Khan starred as the erstwhile journalist — committed to the politics of democratic reform — who could offer no solution to the heroine to end the terror, except her death. But the hero’s choice to die with the (thwarted) suicide-bomber he loves — even as the movement to which she was committed remained undefeated by the state — spoke volumes about the film’s pessimistic assessment of the possibilities for transformation of the nation-state. Despite Khan’s superstar allure, Ratnam’s directorial genius, Gulzar’s unforgettable lyrics and A. R. Rahman’s superb music, the film was a flop in India when it was released to coincide with the 50th anniversary of the country’s Independence.

Dil Se’s critique of liberal democracy was probably too close for comfort for Indian audiences. After all, Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi had been killed by a woman suicide bomber in Sriperumbudur, Tamil Nadu in 1991, and his mother and previous Prime Minister, Indira Gandhi, had been assassinated in 1984 by her Sikh bodyguards after she ordered Operation Blue Star, the storming of the Golden Temple in Amritsar. Notwithstanding Dil Se’s failure in India, the film was a financial success abroad and became the first Bollywood film to make it into the list of the top ten films in the UK box office charts. Dil Se will go down in the annals of film history for its creative merging of the cinematic strategies of Indian commercial and art film.

After Dil Se, Khan took on more roles that challenged the macho ideal of the national Indian hero — the cowardly lover unable to match the strength of character of the woman he loved nor that of the woman who came to love him (Devdas); the bitter and adulterous husband who loses his career and is unable to accept the professional success of his wife (Kabhie Alvida Na Kehna); the captain of the Indian field hockey team who, as a Muslim, is accused of betraying his country when the team loses a crucial match to Pakistan (Chak De); as well as the hapless film extra who dreams of becoming a 1970s-style Bollywood hero and the nerdy secret service agent in Farah Khan’s two brilliant spoofs of the Bollywood genre (Om Shanti Om and Main Hoon Na).

As his screen roles became larger than life, so did Khan’s off-screen public persona. Often described as irresistibly charming, he has a disarmingly grounded quality about him. In an interview for the BBC, when Jonathan Ross asked the star whether he disguised himself to avoid attention when he visits London, Khan quipped “No … I have worked very hard to be recognized …”

As other Bollywood male stars in their late fifties and sixties happily prance on screen with scantily clad twenty-something actresses and dancers, Khan publicly discusses his reluctance to accept romantic roles and his discomfort at having to shoot love scenes with his younger women co-stars. In a recent interview for his latest film (Jab Tak Hai Jan), Khan was asked why he thought Yash Chopra, the director of the film who is since deceased, had waited for almost a decade before making this romantic film with the actor. Khan’s unabashed retort was that maybe Chopra had been waiting for Katrina Kaif and Anushka Sharma — the two female co-stars of the film — to graduate from kindergarten. His self-deprecating answer drew attention to the age gap between himself and his co-stars, an issue that not many Bollywood actors seem willing to discuss.

There are, of course, a number of prominent Muslim actors and directors in the Indian film industry. And like Khan, some of them are in inter-religious marriages and relationships. Khan, however, remains an oddity in this world of celebrities where most Muslim actors and directors adhere to the strict dictates of a secularism that frowns upon public displays of Muslim — but not Hindu — religiosity. Khan’s mannerisms, language and speech articulate a deeply embedded Muslim etiquette (adab) and he is rarely hesitant in public to thank his God for the many blessings with which he feels he has been bestowed. In other words, Khan wears his religious identity on his sleeve.

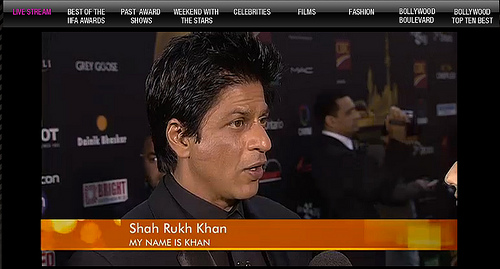

Indeed, as the post 9/11 public climate has become more hostile to Islam and geopolitics are being reshaped by a decidedly anti-Muslim bent, Khan has become more assertive of his identity as a believing Muslim. Three years ago he made and starred in My Name is Khan, a rebuke of the racial profiling of Muslims and South Asians, especially the men, as terrorists. Highlighting the racism and violence of the U.S. state, as well as that of ordinary Americans, the film’s ending was swept up in the Obamania that greeted the election of the first Black president of the U.S. Khan explains that he made My Name is Khan because he was “sick of being mistaken for a crazed terrorist who coincidentally carries the same last name as mine…” (Outlook Turning Points, Jan 2013). Predictably enough, Khan was detained by U.S. immigration upon his arrival in the U.S. to promote the film, and yet again in April 2012, when he was invited to present a lecture at Yale University.

My Name is Khan had some serious flaws, including most glaringly its caricatured representation of African-Americans and its neglect of the role of Islam in shaping the Black anti-slavery tradition as well as contemporary African-American politics. Indian films are littered with racial stereotypes of other Asians, Blacks and Africans, including some of Khan’s films (Rab Ne Bana De Jodi, Phir Bhi Dil Hai Hindustani). Even as he sought to contest stereotypes about Islam and Muslims, My Name is Khan reproduced racial stereotypes of African-Americans in deeply problematic ways. The film also depicted ‘extremist’ Muslims in an overly simplistic manner, squandering the opportunity for an informed engagement with the complexities of the politics of Islamists, including their resistance to U.S. domination of the Muslim world. But the film did reference Hurricane Katrina and the impact of its aftermath on impoverished African-American communities and it highlighted the uneven burden on these communities of the Iraq war. It also sought to articulate a political solidarity between diasporic Muslims, South Asians and African-Americans on the basis of race, a phenomenon almost unheard of in Bollywood.

Khan has not confined his attempts to confront Islamophobic depictions to his on-screen work. In a recent article, ‘Being a Khan’ (Outlook, January 2013), he voiced frustration at repeatedly having to account for acts of violence committed by Muslims: “Whenever there is an act of violence in the name of Islam, I am called upon to air my views on it and dispel the notion that by virtue of being a Muslim, I condone such senseless brutality.”

For some political leaders, Khan has become “a symbol of all that they think is wrong and unpatriotic about Muslims in India.” Ruefully, Khan defends himself against such charges of betrayal, noting, “There have been occasions when I have been accused of bearing allegiance to our neighboring nation rather than my own country — this even though I am an Indian whose father fought for the freedom of India.” Politicians who define him as a foreigner in India have led rallies calling for him to leave his country and return to what they call his “original homeland.” Khan also expressed his concern as a father to protect his children from anti-Muslim, racist and extremist bigotry in the article, and paying homage to his own father, explaining, “My first learning of Islam from him was to respect women and children and to uphold the dignity of every human being” (ibid).

The seductive power of Bollywood has increased immensely with the globalization of communication technologies, and Khan’s own fortunes are inseparable from this phenomenon. The Indian film industry now has stars aplenty, yet Khan’s fans are legion. The ones I have spoken to still love him for his sentimental depictions of the ideal son/lover/father, even though Khan himself challenges such conventional images in different arenas, both on-screen and off.

When he appeared at the Indian International Film Awards ceremony in Toronto last year, his fans rushed to the barricades to get closer to their hero. Visibly alarmed as he saw the police prepare to move in to control the crowd, Khan reached towards his fans in a bid to calm them. As Vancouver prepares to be taken over by TOIFA-mania this week, Shah Rukh Khan will undoubtedly be the centre of attention. But he is an actor who commands attention for much more than his on-screen romantic performances, and his star seems to only shine brighter.

Khan? Naam to suna hi hai.

Sunera Thobani is an Associate Professor at the University of British Columbia and an anti-war activist.