October 27, 1962, is not a date that most people consider especially noteworthy. It certainly doesn’t rate with 9/11 or John F. Kennedy’s assassination, or the fall of the Berlin Wall. But it was by far the most dangerous day in human history — the day the world came perilously close to being devastated by a nuclear holocaust that could have killed as many as three billion people.

I vividly remember that fateful day, which occurred while I was still living in Newfoundland. Baxter Fudge and I were driving in his car to St. John’s to attend a meeting of New Democratic Party activists. I had been provincial leader of the party since its inception, and Bax was a Canadian Labour Congress representative who worked with me during elections and in building the fledging party’s membership.

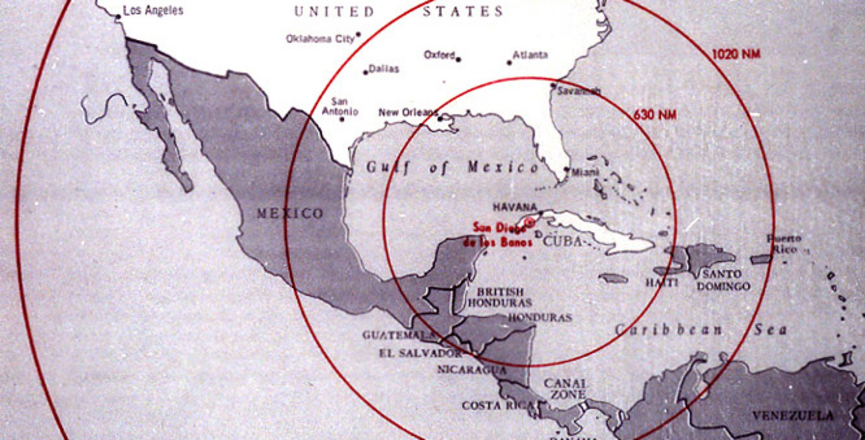

We listened intently to the car radio, which was broadcasting the latest developments in the “Cuban missile crisis.” This momentous clash between the United States and the Soviet Union had steadily been rising to an explosive level. It boiled over when President Kennedy belatedly discovered that Soviet President Nikita Khrushchev had secretly sent 40,000 troops and 100 nuclear war-heads to Cuba.

Khrushchev had been outraged a year earlier when the U.S. installed ballistic missiles in Turkey near the Russian border. He thought that putting missiles in Cuba near the U.S. would restore the balance of nuclear power. Instead it infuriated Kennedy and his political and military advisors. So much so that Kennedy retrieved from his safe the deployment orders to be activated by military forces in the event of an outbreak of war.

The likelihood of such a catastrophic nuclear fray terrified everybody, including Bax and me as we neared the Terra Nova provincial park.

“If the worst happens,” I mused, “what are the chances that Newfoundland will be among the targets of Russian missiles?”

“Not likely,” Bax said. “Most of them will be aimed at the Americans, maybe a couple at the big cities in Canada like Toronto and Montreal, but I can’t see them wasting any of their strikes on Newfoundland.”

“Probably not,” I agreed, “but let’s not forget that the Americans had seven air bases here during the Second World War, one of them, Fort Pepperell, right in the middle of St. John’s.”

We thought about that for a while, then decided it would be prudent to stop and bunk down in one of the park’s cabins overnight, a safe few hundred miles from the provincial capital. That may seem ridiculously precautious today, but remember that this was in the middle of the “Cold War when hostilities between Russia and the U.S. were at their peak.

We didn’t get much sleep in our bunks that night, but were overjoyed the next morning when we found no radioactive clouds drifting overhead on the westerly breeze.

We learned from our car radio that a last-minute accord had been reached, mainly on the agreement that Russia would remove its missiles and troops from Cuba, and the U.S. would remove its missiles from Turkey and refrain from invading Cuba.

A more detailed account of the Cuban missile crisis has just been published. After researching and writing this book, titled Gambling with Armageddon, author Martin J. Sherwin said, “I did not know until I researched this book how close to death we had come.”

He marveled, given the bellicose advice that Kennedy was getting from his advisors (apart from Adlai Stevenson), that any deal to avert war could have been reached. He cited many ways the outcome could have gone horridly wrong for billions of people, probably including, eventually, Bax and me.

Elizabeth Kolbert, who reviewed Sherwin’s book in the New Yorker, compared the pure luck and chance that saved the world from catastrophe on October 27, 1962, to the current situation in the United States.

She noted that Donald Trump has vowed not to renew the last remaining nuclear-arms treaty between America and Russia, which is soon set to expire. “The Trump Administration has already scuttled the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty — it withdrew from the accord last year — and its efforts on behalf of New start have been so halfhearted it seems likely to lapse, too.”

The journal Arms Control Today has noted that, were this to happen, there would “be no legally binding limits on the world’s two largest nuclear arsenals for the first time in nearly five decades.”

“In case you need another reason to lie awake at night, there’s that,” Kolbert added.

Another reason, as well, to pray that Trump is not re-elected in November.

Ed Finn grew up in Corner Brook, Newfoundland, where he worked as a printer’s apprentice, reporter, columnist and editor of that city’s daily newspaper, the Western Star. His career as a journalist included 14 years as a labour relations columnist for the Toronto Star. He was part of the world of politics between 1959 and 1962, serving as the first provincial leader of the NDP in Newfoundland. He worked closely with Tommy Douglas for some years and helped defend and promote medicare legislation in Saskatchewan.

Image: Wikimedia Commons