rabble.ca is a reader-supported site — we count on donations from people like you. Please join us as a paying member (click here) or send a one-off donation (click here) to help us continue our work.

This is the third in a four-part series for rabble.ca. To read the previous article, please click here.

By the time Donna Bertrand died from an overdose of anti-depressants, Dr. Alan Redekopp was prescribing her a daily dose of 1,440 mgs of OxyContin®.

That’s a heck of a lot of a potentially addictive narcotic for a 41-year-old with a sore back.

A Brockville, Ontario, coroner’s inquest — into Bertrand’s 2008 death and that of her friend, 19-year-old Dustin King — is revealing two linked stories.

One story details the tragic death of two people, but the underlying story is about people paying with their lives because of a fractured and ineffectual health-care “system.”

Bertrand, the mother of a 12-year-old boy, was a cocaine addict who got off that illegal drug and then became addicted to OxyContin. She was also being prescribed several other medications for depression and anxiety.

She overdosed in late 2008, just 11 days after King, a troubled teenager, died in her apartment hours after witnesses saw him drink alcohol and snort OxyContin.

King was never prescribed OxyContin; police photographs after his death show that empty pill bottles were scattered throughout the apartment.

“I think Dustin is a victim of an uninformed society surrounding this type of medication,” his mother, Brenda Toupin-Wiles, told the inquest.

The inquest has been told that these deaths took place in a context in which:

• Veterinary students receive five times more education about pain management than medical students;

• Testifying under oath at the inquest, Redekopp (apparently like many other physicians) acknowledged that he took important information about how to prescribe OxyContin from sales representatives for Purdue Pharma, the manufacturer of the drug;

• Media reports and phone calls from worried communities prompted action by the regulatory body for doctors. (Health Canada does not conduct systematic tracking of the impact of prescription drugs on Canadians after the drugs are on the market.)

• Pharmacists and doctors rarely talk to each other, even when problem prescriptions are spotted; Brockville pharmacist Rock Coulombe, who also testified, said relations with doctors are “often antagonistic”;

• Very little is known about the risk/benefit of taking prescription painkillers over long periods for chronic pain;

• The price tag for alternate ways to address chronic pain, such as physiotherapy and massage, can be prohibitive for lower-income Canadians who may, however, be able to get prescription painkillers at minimal cost through provincial plans;

• Access to specialized pain and addiction clinics is very limited.

Although the inquest is taking place in Ontario, almost all of these problems are Canada wide.

The problem of prescription drug addiction “is highly tied into the healthcare system,” said Beth Sproule, a pharmacist with the Centre for Addiction and Mental Health in Toronto and a researcher in the area.

Narcotics are needed to treat pain, so the challenge is to keep them available but prevent people from having problems with them, she told the inquest.

A portion of patients with no history of addiction run into trouble with these pharmaceuticals, yet very little research has been done on “the pathways to prescription addiction.”

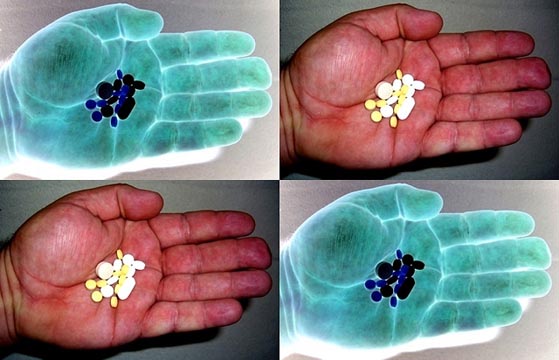

OxyContin is one of several prescription opioids, but because of its slow-release formulation — once ingested, the active ingredient oxycodone is released more gradually than by immediate release painkillers — it contains far more oxycodone than narcotics such as Percocet and Percodan.

Bertrand was prescribed OxyContin in both 40 and 80 mgs; in comparison, a Percocet® tablet contains only 5 mgs of oxycodone.

Witness Vincent Shaver, a former addict, told the inquest that he used to trade his entire monthly prescription of 120 Percocets for three OxyContin pills, which he would crush and snort.

Redekopp, who qualified as a pharmacist before becoming a family doctor, told the inquest he received visits, “perhaps every two months through the years,” from sales representatives for Purdue Pharma, the manufacturer of OxyContin. (The drug was approved for marketing in Canada in the mid 1990s.)

The sales reps told him that OxyContin “was a drug of low abuse potential,” Redekopp said, though he indicated that they also told him the drug “could be addictive.”

A maximum dose for prescribing OxyContin was never mentioned by the sales reps, he told the inquest.

“So you were never told what was a dangerous level of the drug?” Crown Attorney Curt Flanagan asked.

“No, there was no talk of that,” the doctor replied. “I was told many pain clinics use doses of 900 to 1000 mgs very effectively.”

By 2010, however, concern about opioid (and in particular OxyContin) misuse was impossible to ignore, and Canadian doctors were being told that 200 mgs a day of morphine (equal to about 120 to 133.6 mgs of oxycodone) for chronic non-cancer pain was a “watchful dose.”

To prescribe more “requires careful reassessment of the pain and of risk for misuse, and frequent monitoring with evidence of improved patient outcomes,” according to the April 2010 Canadian Guideline for Safe and Effective Use of Opioids for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain. (The guideline was funded by a collaboration of medical regulatory bodies across Canada; no pharmaceutical company money was involved.)

Redekopp, a solo practitioner with about 2,500 patients, accepted Bertrand as a patient on October 12, 2007 — less than 14 months before her death — and prescribed 120 mgs a day of OxyContin on that first visit. He told the inquest he continued to increase the daily dosage based solely on her self-reports of pain.

The College of Physicians and Surgeons of Ontario (CPSO) was prompted to take action two-and-a-half-years ago in response to media reports about opioid misuse in various communities, college registrar Dr. Rocco Gerace told the inquest.

“OxyContin was becoming increasingly a problem and the whole family of oxycodone drugs,” he said.

The CPSO was also getting urgent phone calls from communities around the province that were seeking help to deal with mounting problems with prescription drug addiction, diversion and misuse, CPSO research and evaluation manager Rhoda Reardon told the inquest.

“They were having problems and they knew that doctors were part of the problem … generally speaking, the one [drug] you heard about was OxyContin.”

In response, the college convened a range of stakeholders and last September published Avoiding Abuse, Achieving a Balance: Tackling the Opioid Public Health Crisis.

One of the report’s 31 recommendations was that there should be an “inter-professional model of care” for treating patients with chronic pain that includes nurses, pharmacists, physiotherapists, occupational therapists psychotherapists and counsellors.

“The totality of pain care should be funded by the government,” Gerace told the inquest.

When joint doctor/pharmacist workshops were held in eight Ontario communities, “the biggest surprise we had… was the lack of awareness of the importance of physicians and pharmacists talking to each other,” Reardon said.

The inquest was earlier told that, in general, doctors do not welcome questions from pharmacists. There is “a sense that physicians have all the information and must know what they are doing,” said Anne Resnick, director of professional practice programs for the Ontario College of Pharmacists.

Coulombe testified that because of “red flags” that Bertrand’s OxyContin was being abused or diverted — the number of times she claimed her pills had been lost or stolen — he told her in September 2008 that he would no longer fill her prescriptions.

Coulombe said he had previously expressed his concerns to Redekopp, and did inform him of this decision to terminate Bertrand. Redekopp continued to prescribe escalating doses of the narcotic.

Lawyers from the firm Borden Ladner Gervais are representing Purdue Pharma at the inquest, which continues this week.

Ann Silversides has a Canadian Institutes for Health journalism award to research issues related to prescription painkillers.

Thank you for choosing rabble.ca as an independent media source. We’re a reader-supported site — visited by over 315,000 unique visitors during the election campaign! But we need money to grow. Support us as a paying member (click here) or in making a one-off donation (click here).