In the discourse around Israel and Palestine, the words “Zionism” and “Zionists” are employed liberally. Recently, however, advocates for Israel have made these terms controversial, insisting that the mere use of them refers to Jews and is therefore tantamount to anti-Semitism.

Independent Jewish Voices Canada (IJV) rejects this characterization, and I would suggest that insisting that anti-Zionism=anti-Semitism is part of a campaign of pro-Israel “cancel culture” which, along with the definition of anti-Semitism promoted by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, is meant to silence criticism of that state, its policies and practices. In the fevered imagination of the cancelers, “Zionist” joins “Apartheid,” “ethnic cleansing” and “settler colonialism” as verboten language. Will every term used to discuss conflict in the Middle East soon be banned?

Here are several recent examples:

- At the behest of some pro-Israel organizations, Facebook has been considering a policy making the term “Zionist” fall within the rubric of hate speech. A petition against the proposal, organized by IJV and a coalition of dozens of groups, collected more than 54,000 signatures, including from artists like Michael Chabon, Peter Gabriel and Wallace Shawn.

- On Twitter, Harsha Walia, the former CEO of the BC Civil Liberties Association (BCCLA), used the term “Zionists” to describe some of the individuals who had been trolling her online. Responding on Twitter, Richard Marceau, the Vice President, External Affairs and General Counsel for the Centre for Israel and Jewish Affairs, condemned Walia’s remark as anti-Semitic.

- In a comment on the “Azarova Scandal” at the University of Toronto Law School (wherein pressure from pro-Israel organizations led the school to rescind an offer of employment to a candidate who had criticized Israeli policies), Professor Terezia Zoric, the president of the University of Toronto Faculty Association, declared that an “entitled powerful Zionist minority” was targeting the association. B’nai Brith Canada denounced Zoric’s words as anti-Semitic and demanded she resign her position and that the university dissociate itself from her remarks.

Those suggesting that mere use of the term “Zionist” is anti-Semitic argue, as David Matas of B’nai Brith Canada does:

“The bigoted often use double entendres, words that have both an innocent meaning and a coded meaning to their bigoted cohort…They use dog whistles, sounds with the intent that only their bigoted cohort will appreciate.”

What credence should we give to this argument? And, even if our credence is strained, does the claim perhaps deserve some benefit of the doubt?

The best place to start is to explore the plain rather than any imputed meaning of the term “Zionism.”

The Jewish Virtual Library is a project of The American-Israeli Cooperative Enterprise (AICE) “established in 1993 as a non-profit and nonpartisan organization to strengthen the U.S.-Israel relationship.” This should provide its bona fides as “the horse’s mouth” when it comes to the definition of the term Zionism. According to the JVL:

The term “Zionism” was coined in 1890 by Nathan Birnbaum.

Its general definition means the national movement for the return of the Jewish people to their homeland and the resumption of Jewish sovereignty in the Land of Israel.

Since the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, Zionism has come to include the movement for the development of the State of Israel and the protection of the Jewish nation in Israel through support for the Israel Defense Forces.

In other words, Zionism began as support for Jewish sovereignty in the so-called “Holy Land,” and since 1948 has evolved into support for Israel, its policies and practices.

Pro-Israel advocates believe that Zionism is synonymous with — indeed, the essence of — Jewish identity, but that is far from the truth.

Zionism is not primarily a religious, or in any way a Jew-defining, tenet. Rather, it is a political movement rooted in a political doctrine. Like all political doctrines, it has been subject to great debate and disagreement both within and beyond the Jewish people.

It must be emphasized that not all Jews are Zionists. And not all Zionists are Jews. Furthermore, the vast majority of Zionists in the world today are Christians!

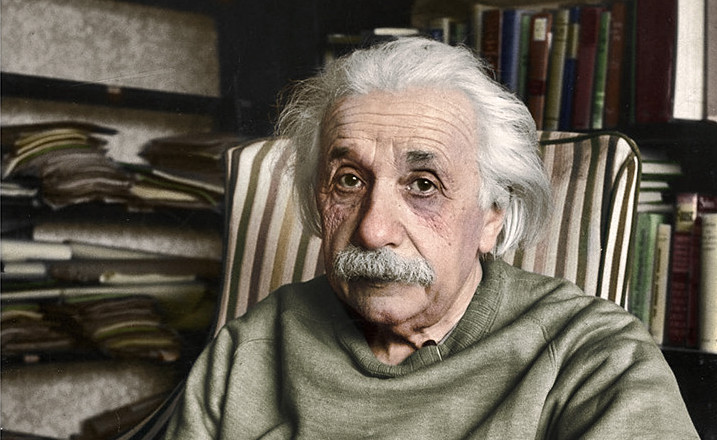

Contrary to the current Zionist narrative, adherence to Zionism was a minor ideological strain among the world’s Jews until the end of World War II, with the revelations of the Holocaust and the founding of the State of Israel. Even after World War II, some groups of religious Jews, Bundists, many communists and other subsets of the Jewish diaspora rejected political Zionism. Prominent Jewish intellectual icons, including Sigmund Freud, Albert Einstein and Hannah Arendt, all rejected political Zionism. Opposition to Zionism was widespread among Jews. Israeli historian Tom Segev, in his biography of Israel’s first Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion, explains that:

“According to Paula [Ben Gurion’s future wife], her [American Jewish] family opposed her marriage [in 1917] to Ben-Gurion because he was a Zionist.”

Intra-community differences on Zionism continue to exist. A 2018 survey of the Canadian Jewish population conducted by EKOS shows that Jewish attitudes toward Israel are not the monolith that institutional Jewish organizations depict. Jewish opinion is seriously split on many central questions related to Israel and Zionism. More than a third (37 per cent) of respondents have a negative opinion of the Israeli government; almost equal proportions oppose (45 per cent) and support (42 per cent) the U.S. decision to recognize Jerusalem as the capital of Israel; almost a third (30 per cent) think that the Palestinian call for a boycott of Israel is reasonable; 34 per cent oppose the Canadian Parliament’s condemnation of those who endorse a boycott of Israel; and 48 per cent agree that “accusations of anti-Semitism are often used to silence legitimate criticism of Israeli government policies.” These results indicate that between one-third and one-half of Canadian Jews are not intransigent in their support of Israel.

In a recent poll of U.S. Jews, one-third of those under 40 agreed with the term “apartheid” when used to describe the Israeli regime and its treatment of the Palestinians.

Disagreements about fundamental issues abound even within the Zionist movement, both historically and down to today. These disagreements manifest themselves in tendencies that range from “cultural Zionism” (whose adherents insist only that Jews maintain some, however tenuous, connection with the “Holy Land”), to mainstream Zionists (who support Jewish sovereignty in some part of that region) to so-called “Revisionist Zionists” (followers of Vladimir Jabotinsky) and Kahanists who support aggressive domination, expansion and the use of wanton cruelty toward the Palestinian population.

Another reason that Zionism is not synonymous with Jewishness is that the large majority of Zionists are not Jews, but evangelical Christians. Just in the U.S. and Canada, Christian Zionists number approximately 70 million. There are approximately 8 million Jews in the two countries.

It is a difficult fact for Zionists to reconcile with their beliefs, but many anti-Semites are great supporters of Israel. American white supremacist Richard Spencer, who has called himself “a white Zionist,” praises Israel’s ethnic exclusivity and harsh treatment of Muslims. As Jewish-American critic Peter Beinart reminds us:

“Some of the European leaders who traffic most blatantly in anti-Semitism — Hungary’s Viktor Orbán, Heinz-Christian Strache of Austria’s far-right Freedom party and Beatrix von Storch of the Alternative for Germany, which promotes nostalgia for the Third Reich — publicly champion Zionism too.”

In addition to the factual, historic or scholarly definition of “Zionist,” the term is used among critics of Israel as a convenient catchphrase, to refer to their ideological opponents. For example: “the Zionists are touting the IHRA definition of anti-Semitism.” Sometimes “Zionist” is used with disdain, as a pejorative, but most often its use constitutes an expression of antipathy to the Israeli regime and its avid supporters, not hatred of Jews. It is difficult for anyone in good conscience to interpret the references to “Zionists” made by Harsha Walia and Terezia Zoric as anything other than that. They did not mean that Jews are giving them grief, but rather avid supporters of Israel.

It would be impossible to deny that some anti-Semites, somewhere, use the term “Zionist” as a code word to refer to Jews in general. Many words and phrases have a double, even a triple, entendre. But to insist that such use is anything other than exceptional for the term “Zionist” smacks of paranoia, or conscious and strategic dissembling.

Larry Haiven is a founding member of Independent Jewish Voices Canada and Professor Emeritus at Saint Mary’s University in Halifax.

Image: Alfred Eisenstaedt/Life Magazine/Creative Commons