January is often a time of reflection and goal-setting — and a good time to get in some extra reading as we tuck in on those colder days and nights.

We can all learn a lot from history, and how it impacts our present, from a good book. I suggest reading Frontline Farmers: How the National Farmers Union Resists Agribusiness and Creates our New Food Future, edited by Annette Desmarais.

Published by Fernwood, Frontline Farmers was launched in November 2019 in Winnipeg during the 50th anniversary convention of the National Farmers Union.

Depending on the reader’s knowledge of agrarian activism in Canada, Frontline Farmers is either an insightful reminder of various campaigns and struggles, or an excellent introduction to agrarian activist history. For all of us, it is a great primer regarding the ongoing issues in Canadian agriculture.

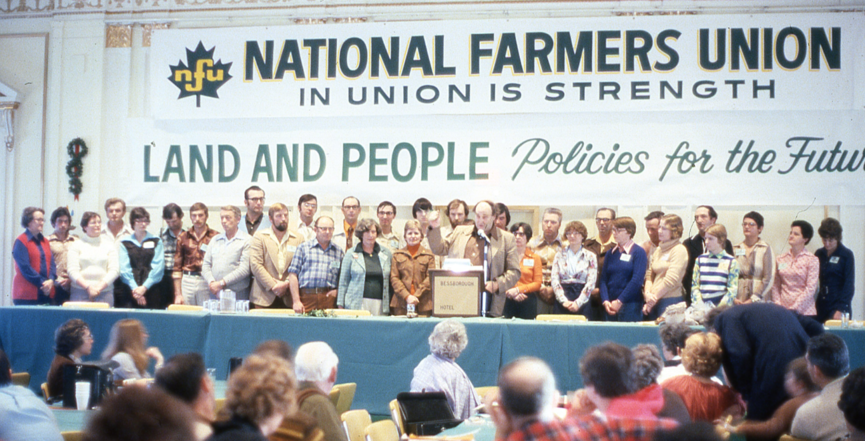

The NFU was founded in Winnipeg in July 1969 with more than 2,000 farmers gathered for its first convention. It comprised a merger of several provincial farm organizations from across Canada. By 1970, the NFU had a federal charter and it remains the only farm organization in Canada recognized by an act of Parliament. The word “union” is powerful and purposeful, since the NFU was created with the firm belief that farmers, like workers, deserve the right to bargain collectively.

Throughout the last 50 years, the NFU has led various campaigns pushing for those bargaining rights, along with the expansive issues of social justice and food sovereignty. The goal of collective bargaining for family farmers is still elusive, but the NFU’s campaigns to reinforce the importance of family farming and fair pricing have been key to public education about food issues. Frontline Farmers shows that the NFU has punched way above its weight over the last five decades. Despite having limited resources, and being dependent on volunteer effort and energy (with most members already having more than enough on-farm work to do), the NFU has acted strategically and helped us all understand the key role that family farmers play in each of our lives.

The book details many campaigns, although, as noted by Nettie Wiebe, a grain farmer and former president of the NFU, Frontline Farmers is not a “comprehensive” history of the NFU. The book does, however, help map some of the movement’s key struggles and explains how the NFU has forged coalitions around rural and urban issues. On its 40th anniversary in 2009, the NFU published an important document detailing tractor demonstrations, the fight to keep the Crows Nest Pass freight rate, challenging plant breeder’s rights, and many more. The pamphlet is worth reviewing alongside Frontline Farmers.

Frontline Farmers is based on inspiring interviews with dedicated NFU members and organizers. As Wiebe writes:

“The conversations, recollections and stories in this book offer a glimpse of the last 50 years of NFU activism, values, and analysis. They expose the ongoing dynamic relationship between food production, ecological sustainability and social well-being that is nurtured by progressive, organized farmers and citizens.”

Boycotting Kraft

The campaign to boycott Kraft is an important story, and it is great to see it chronicled in the book in such detail.

There are still people who do not buy Kraft products because of the NFU boycott, which began shortly after the union was founded. I am among those who still shun anything labelled Kraft, and have often wondered how much revenue that corporation has lost because of the NFU’s resistance to corporate control, and because of the principled stubbornness of its members and people like me.

This first section of Frontline Farmers looks at why and how the Kraft boycott began in the early 1970s. The boycott was a response to Kraft taking over smaller dairy manufacturers and production operations in Ontario, moves which concentrated Kraft’s control over the dairy industry and drove small producers out of business. While orderly marketing is rightly supported by the NFU, the Kraft boycott was a clear example of what happens when small farmers have little or no say in the pricing system, despite orderly marketing. The Kraft boycott was an active and national campaign for many years.

Frontline Farmers chronicles how the boycott strengthened coalitions with labour and non-farm consumer groups, and how the lessons learned from the boycott helped inform the NFU’s ongoing activism. This section of the book also mentions important initiatives such as the People’s Food Commission of the late 1970s, which culminated in the publication of The Land of Milk and Money and inspired the more recent People’s Food Policy Project, organized by Food Secure.

The book also mentions the White Crow Campaign, organized to fight against the dismantling of the Crows Nest Pass freight rates. The NFU fought to retain the Crows Nest Pass freight rates in a campaign that lasted 15 years.

Both of these grassroots initiatives led to growing awareness of policy work related to food production. More detail on these two initiatives would have been welcome, but I am happy that they were at least mentioned. The grassroots campaigns of the NFU are too numerous to all be included in a single tome.

Grassroots organizing

Frontline Farmers is based on interviews with those involved in NFU campaigns and initiatives. These campaigns range from the protection of seed rights, the Canadian Wheat Board, saving prison farms, protecting farm land in P.E.I., and the importance of international solidarity with small farmers by helping to create and support La Via Campesina.

The voices in the book also provide insight, analysis, and organizing techniques on issues related to bovine growth hormone, genetically modified wheat, and Monsanto’s grip on agriculture.

Chapter 4, “Protecting Seed,” provides further information on the “corporate seed-chemical value chain” and initiatives that defend farmers rights to save seed. Those interviewed in this chapter also explain the importance of biodiversity, the value of local control of seed by farmers, the campaigns undertaken to stop plant breeders’ rights legislation (beginning in the late 1970s) and the more recent ongoing actions to promote the NFU’s “Fundamental Principles of a Farmers Seed Act.”

Chapter 5 chronicles the story of the Canadian Wheat Board, and its importance for farmers, their income, and the national economy. As Steward Wells, former president of the NFU, explains in this chapter:

“You have to keep in mind that this legislation (re the CWB) created the largest transfer of wealth away from farmers over to the grain trade in the history of the country.”

The loss of the Canadian Wheat Board in 2012 under Stephen Harper’s federal Conservative government may well become known as one of the most corrupt political heists in this country’s history. With a single piece of legislation, the Harper government destroyed 70 years of CWB history — and along with it the protection that family farmers had come to almost take for granted in terms of collective marketing and price-pooling.

Onward

Later chapters bring an air of optimism to the farm movement, as they cover topics that include agrarian feminism in Chapter 9, and Indigenous-settler solidarity in Chapter 12. Chapter 10 describes the rise of a new generation of young agrarians struggling to make a living while standing tall on issues related to seed, climate change and international solidarity. Cammie Harbottle, an NFU member from Tatamagouche, Nova Scotia, explains in an interview in Chapter 10:

“I think the youth are brining new energy to the NFU. When all the farmers get older and there are no young people filling their shoes, no young people living on farms who want to take over, it is not very hopeful. I think it is inspiring to see young people who are involved in farm politics who want to make a difference, who want to make a livelihood from farming and who are dedicated to the issues and to the work that needs to get done to make that change possible.”

The younger generation — the new agrarians — provides us with a new opportunity. Best if we not miss it.

While the stories in Frontline Farmers are of struggle, and at times of battles lost, the re-telling of this history bears testimony to strength, commitment, resilience and the quest for justice. These NFU stories are inspiring, and need to be known, respected and remembered. They show that we need to continue forging alliances with progressive family farmers and support their efforts as best we can. The NFU helps to show us that the urban-rural divide does not have to exist.

As noted by Wiebe in the book’s first chapter: “Social activism demonstrates hope.”

That hope is why this book is such a good and important read.

Lois Ross is a communications specialist, writer and editor, living in Ottawa. Her column “At the farm gate” discusses issues that are key to food production here in Canada as well as internationally.