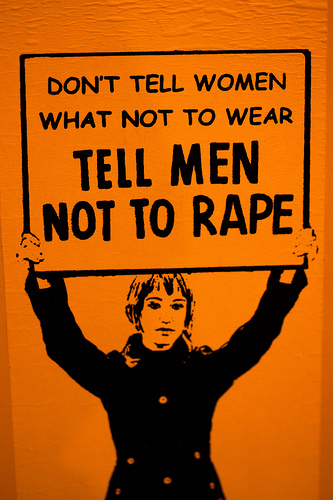

Yesterday morning, I read and was infuriated by Emily Yoffe’s Slate article, “College Women: Stop Getting Drunk”. Just once, I’d love it if anyone — especially (radically!) a woman — actually wrote an article that tells men not to be rapists, instead of suggesting that “putting all the responsibility of preventing sexual assault on the victims” is somehow a feminist point of view. So, for fun, I rewrote her article. Most of the words below are her own. I changed only references to gender. Everywhere that Ms. Yoffe said something about giving “warnings to women about their behavior,” I changed it to a warning for men. I bolded the changes I made, to make it easier for you to see them.

That’s all I did, the rest (including all links to other articles and studies) is still in her own words. Just imagine a world in which articles like this actually got written.

College Men: Stop Raping Women

It IS sexual assault. And yet we’re reluctant to tell men to stop doing it.

In one awful high-profile case after another — the U.S. Naval Academy; Steubenville, Ohio; now the allegations in Maryville, Mo. — we read about a young man, sometimes only a boy, who goes to a party and ends up raping a girl. As soon as the school year begins, so do reports of female students sexually assaulted by their male classmates. A common denominator in these cases is alcohol, often copious amounts, enough to render the young man incapable of distinguishing right from wrong. But a misplaced fear of blaming the perpetrators has made it somehow unacceptable to warn inexperienced young men that when they get wasted, they are putting themselves at risk of becoming rapists….

Let’s be totally clear: Perpetrators are the ones responsible for committing their crimes, and they should be brought to justice. But we are failing to let men know that when they drink to excess, they can end up becoming these very perpetrators. Young men are getting a distorted message that having sex with any woman they want — regardless of whether the woman consents — is their right. The real message should be that when you drink so much that you lose the ability to be responsible for actions, you drastically increase the chances that you will become a sexual predator and a threat to women around you. That’s not villainizing all men; that’s trying to prevent them from becoming rapists.

Experts I spoke to who wanted young men to get this information said they were aware of how loaded it has always been to give warnings to men about their behavior. “I’m always feeling defensive that my main advice is: ‘Don’t rape. Don’t make yourself vulnerable to the point of losing your cognitive faculties so that you think it’s ok to rape,'” says Anne Coughlin, a professor at the University of Virginia School of Law, who has written on rape and teaches feminist jurisprudence. She adds that by not telling them the truth — that they are responsible for their own actions — she worries that we are “infantilizing men.”

The “Campus Sexual Assault Study” of 2007, undertaken for the Department of Justice, found that the popular belief that many young rape victims have been slipped “date rape” drugs is false. “Most sexual assaults occur after voluntary consumption of alcohol by the victim and assailant,” the report states. But the researchers noted that this crucial point is not being articulated to young and naïve men: “Despite the link between substance abuse and sexual assault it appears that few sexual assault and/or risk reduction programs address the relationship between substance use and sexual assault.” The report added, somewhat plaintively, “Students may also be unaware of the image of predatoriness projected by a visibly intoxicated individual.”

“I’m saying that men are responsible for sexually victimizing women,” says Christopher Krebs, one of the authors of that study and others on campus sexual assault. “When your judgment is compromised, your risk of becoming a rapist is elevated.”

The culture of binge drinking — whose pinnacle is the college campus — does not just harm men. Surveys find that more than 40 percent of college students binge drink, defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention as consuming five or more drinks for a man and four or more for a woman in about two hours. Of those drinkers, many end their sessions on gurneys: The National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism estimates that about 600,000 students a year are injured due to their drinking, and about 700,000 are assaulted by a classmate in a drunken encounter. Some end up on slabs: About 1,800 students a year die as a consequence of alcohol intake….

As a parent with a son heading off to college next year, I’ve noted with dismay that in some college guidebooks almost as much space is devoted to alcohol as academics. School spirit is one thing, but according to The Insider’s Guide to the Colleges, when the University of Florida plays Florida State University, “Die-hard gator fans start drinking at 8 am. No joke.” I guess I’m supposed to be reassured to read that at the University of Idaho, “Not everyone is an alcoholic.”

“High-risk alcohol use is the one thing connected to all, and I mean all, the negative impacts in higher education,” says Peter Lake, director of the Center for Excellence in Higher Education Law and Policy at Stetson University College of Law and author ofThe Rights and Responsibilities of the Modern University. He cites the problems of early student attrition and perpetually disappointing graduation rates.

I’ve told my son that it’s his responsibility to take steps to ensure he does not become a sexual abuser. (“I hear you! Stop!”) The biological reality is that women do not metabolize alcohol the same way as men, and that means drink for drink women will get drunker faster. I tell him I know alcohol will be widely available (even though it’s illegal for most college students) but that he’ll have a good chance of knowing what’s going on around him if he limits himself to no more than two drinks, sipped slowly — no shots! — and stays away from notorious punch bowls. If male college students start moderating their drinking as a way of looking out for their female counterparts — and looking out for your own self-interest should be a primary human principle — I hope their restraint reduces the likelihood that they will victimize women.

If I had a daughter, I would tell her that it’s in her self-interest not to be the drunken sorority girl who finds herself accusing a classmate of raping her. Because this University of Richmond student is an example of what would probably happen. He was acquitted in one of the extremely rare cases in which a campus rape accusation led to a criminal trial.

The federal government has taken steps to acknowledge the campus sexual assault problem by using the pressure of Title IX, which prevents sex discrimination in education, and should require schools to improve programs to educate students about not perpetrating sexual assaults and to deal more effectively with it. (Occidental College students filed a Title IX complaint against the school after administrators allowed a serial rapist to continue his studies.) Educating students about rape, teaching them that by definition a man who does not ask for or get consent from a woman is a rapist, is crucial. Also important are bystander programs that instruct students in how to intervene to prevent sexual assault on or by drunk classmates and about the need to get dangerously intoxicated ones medical treatment.

But nothing is going to be as effective at preventing alcohol-facilitated assaults as a reduction in alcohol consumption, or perhaps a radical strategy to educate men about not preying on vulnerable or intoxicated women, and not allowing themselves to become rapists. The 2009 campus sexual assault study, co-authored by Krebs, found campus alcohol education programs “seldom emphasize the important link” between men’s voluntary alcohol and drug use “and becoming a perpetrator of sexual assault.” It goes on to say students must get the explicit message that limiting alcohol intake and avoiding drugs “are important sexual assault prevention strategies.” I think it would be beneficial for younger students to hear accounts of alcohol-facilitated sexual assault from male juniors and seniors who’ve perpetrated it.

Of course, perpetrators should be caught and punished. But unfortunately when you are dealing with intoxication and sex, there are the built-in barriers for women to report sexual assaults (which are rarely prosecuted anyway) — including shame, guilt, and a well-founded fear of not being believed, because our society still blames victims and puts the onus on them to “prove” that they have been assaulted, in spite of the fact that intoxication (both voluntary and involuntary) can result in incomplete memories and differing interpretations of intent and consent. To establish if a driver is too drunk to be behind the wheel, all it takes is a quick test to see if his or her blood alcohol exceeds the legal limit. There isn’t such clarity when it comes to alcohol and sex. According to “Prosecuting Alcohol-Facilitated Sexual Assault,” a study by the National District Attorneys Association: “Generally, there is not a bright-line test for showing that the victim was too intoxicated to consent, thereby distinguishing sexual assault from drunken sex.” Bringing these cases is, the study notes, “an extreme challenge.” Besides, college student victims rarely turn to law enforcement or even campus authorities, as the students responsible for sexual assault rarely face punishment, while their victims’ lives are turned upside down.

Some think changing the campus drinking culture requires lowering the drinking age from 21 years.The Amethyst Initiative, started by chancellors and presidents of universities and colleges, and the group Choose Responsibility both make the case that since most college drinking is illegal, that gives it the allure of the forbidden, encourages excess, and increases danger because students are reluctant to turn to the authorities when drinking gets out of hand. But changing the drinking age is a policy that’s gotten little traction.

Others think that changing campus rape culture requires less focus on how the victims behave and what their drinking habits are, and more focus on perpetrators’ behaviour. Educating men about the dangers of becoming sexual abusers — with or without the aid of alcohol or drugs — and giving them the tools to ensure they do not become rapists, might just be the key.

Lake says that administrators often take an overly simplistic approach to curbing sexual assault by approaching it as primarily an issue of alcohol consumption on the part of female victims, as opposed to a learned behavioural issue on the part of male perpetrators. In the 1990s that meant crackdowns, which he says sent a lot of drinking off campus, probably elevating the risks. He says rape culture is so entrenched it requires a multifaceted approach that includes education, enforcement, and social engineering. And yet, administrators are focused mainly on the issue of alcohol use. For example, he says weekends often begin on Thursday because many colleges have few, if any, Friday classes. “In the alcohol wars, you can see where battlefields are and where booze has beaten the academy,” he says. “The academic program has receded, and they’ve given up on Friday.” He says a full day of classes should be scheduled on Friday, and it should be a standard day for tests and exams. He says since millennials (like young people forever) keep vampire hours, unless there are evening alternatives on campus, those purveying alcohol will win.

And who is it purveying alcohol? In some cases it’s a type of serial predator who encourages his victim to keep pouring the means of her incapacitation down her own throat. Researchers such as Abbey and David Lisak have explored how these men use alcohol, instead of violence, to commit their crimes. Lake observes that these offenders can be campus leaders, charming and well liked — something that comes in handy if they are accused of anything. “They work our mythology against us,” says Lake. “We would like to see our daughters hang out with nice boys in navy blue blazers – and for some inexplicable reason, we do not believe that those boys are capable of being rapists, but it’s hardly surprising that they are capable of it, since we don’t focus much of our time on trying to teach them not to rape.”

The three young women I spoke to who were victims of such men attended different colleges, but their stories are so distressingly similar that it sounds as if they were attacked by the same young man, who was probably never given any rape prevention education in an effort to ensure he did not become a rapist. In each case the woman lost track of how much she’d had to drink. Then a male classmate she knew took her by the hand and offered her an escort. Then she was raped by this “friend.” Only one, Laura Dunn, reported to authorities what happened, more than a year after the fact. In her case she was set upon by two classmates, and the university declined to take action against either one….

We should all lament the whole campus landscape of alcohol-soaked hookup sex and rape. Men are encouraged to “score”, which ignores all the risks for them to become sexual predators. Men become aggressive and disregard women’s inability to give consent. Then women get violated. Who does this culture benefit? Sexual predators.

I get what all the beer bongs, flip cup, power hours, even butt chugging is about. (OK, maybe not butt chugging.) It’s fun. In Getting Wasted: Why College Students Drink Too Much and Party So Hard, Ohio University sociologist Thomas Vander Ven got an inside look at what he calls “the shit show.” He writes, “To some university students, the decision to drink at college is a redundancy. To them, college means drinking.” Vander Ven documents the pleasure that group intoxication brings: the suppression of inhibitions and self-consciousness, the collective hilarity, the thrill of engaging in potentially perilous adventures, and the sense of camaraderie. Even nursing hangovers and regrets becomes a group endeavor, a mutual post-battle support group. Collective intoxication is intoxicating, one of the reasons that it’s been so difficult to reduce the amount of binge drinking on campuses. Of course, when talking about campus drinking, we often neglect to mention that we live in a society that only believes it is acceptable for men to have all that “fun”. For women, it is a dangerous game. After all, if they get drunk, they might get raped — and it is their responsibility to ensure that they are not victimized by dangerous assailants. Fortunately for (most) men, they don’t need to worry about those kinds of consequences.

I know many people will reflect on their own bacchanalian college experiences with nostalgia and say the excesses didn’t hurt them — because if they were hurt, it was by human assailants, not a pitcher of beer. So I will present myself as an example that it’s possible to get drunk without being raped. I enjoy drinking and have been incredibly lucky to have not been the victim of a sexual predator in my life. Many women are not that lucky, and we don’t tell them often enough that it’s not their fault for drinking — it’s the rapist’s fault for raping them. Still, as a young person, I did my share of fun, crazy, silly, stupid, and ill-advised things. But at least I always knew that my drinking was not responsible for the behaviour of another person who wished to do me harm.

Lake says that it is unrealistic to expect colleges will ever be great at catching and punishing sexual predators; that’s simply not their core mission. Colleges are supposed to be places where young people learn to be responsible for themselves. Lake says, “The biggest change in going to college is that you have to understand that becoming a rapist begins with you. For better or worse, fair or not, just or not, you are the one who decides to rape, even though if you do, sadly it is unlikely that appropriate consequences will fall on your head.” I’ll drink (as many drinks as I damn well please) to that.

Katarina Gligorijevic is a writer, producer and musician living in Toronto. You can buy her writing here or see her film production company, Ultra 8, here. Why don’t you follow her on Twitter while you’re at it too. A longer version of this article originally appeared on her blog. It is reprinted here with permission.

Image: flickr/tensory