Over three days last week in Vancouver, lawyers for the Hupacasath First Nation and Department of Foreign Affairs and International Trade argued before a federal court judge on whether the government has a duty to consult First Nations before ratifying international treaties such as the Foreign Investment Protection and Promotion Agreement (FIPA) with China. The landmark case exposes the extra-legal rights (to profit) that foreign companies have under Canadian investment treaties, and how those rights could undermine First Nations governance and Indigenous rights guaranteed in the Constitution.

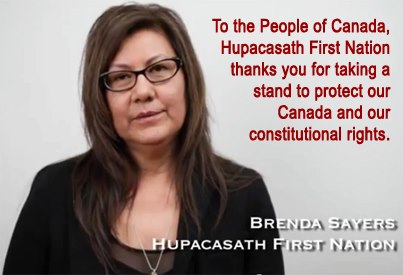

Hundreds of people rallied in support of the Hupacasath outside the courtroom and in solidarity actions across the country. Lawyers for the small Vancouver Island First Nation expect the judge to rule on the case before September and hope the federal government will refrain from ratifying the FIPA before then.

Mark Underhill represented the Hupacasath in federal court. This week he summarized the case for groups that have supported the Hupacasath over the past seven months, and he shared the memorandum of fact and law presented to the court. Underhill says the argument is split into two parts: a treaty argument (the duty to consult) and an argument related to a change in the governance landscape, or the balance in the federal-First Nation negotiating relationship, that FIPA and treaties like it bring about.

I pull some of those arguments out here and will talk about the government’s counter-arguments in another post.

Underhill makes it clear to the judge that no consultations were held with First Nations in respect of the FIPA. “Indeed,” says the memorandum, “no assessment was made by Canada as to (a) potential adverse impacts of the FIPPA on Aboriginal Rights and Title, (b) the implications of Chinese investment in land or resources which might be subject to Aboriginal Rights and Title or (c) how First Nations governance might be affected by the FIPPA.”

(The Hupacasath court documents refer to the FIPPA but I prefer to use FIPA. The extra “P”– the word “promotion” — is a Harper government fantasy, added recently for propaganda purposes, since there is little evidence these treaties actually promote investment in either direction. They are strictly about protecting investors not just from abuse by the state but also from public policies that would limit profits.)

The government had the opportunity to address the oversight in response to letters requesting consultation from the Hupacasath First Nation (October 26, 2012), the Union of B.C. Indian Chiefs (October 30), the Serpentine River First Nation (October 31), the Chiefs of Ontario (November 5), the Tsawwassen First Nation (November 29), the Special Chiefs Assembly of the Assembly of First Nations (early December), and the Dene Tha’ First Nation (March 13). But “no substantive response” to these letters ever came, says the memorandum.

This last correspondence from the Dene Tha’ explains the problem of not consulting with respect to the management of resources on First Nations territory. According to the memorandum:

There is significant oil and gas development, including shale gas development (“fracking”), in the Traditional Territory of the Dene Tha’. The Dene Tha’ are concerned about the impact of this activity on the land, water and resources which they rely upon in the exercise of their aboriginal and treaty rights. Some of this activity is being carried out by Nexen, which, as above, has recently been taken over by the Chinese state owned company CNOOC. Chief Ahnassay expressed his concern to the Ministers that FIPPA would make it more difficult to create protected spaces in the Dene Tha’s Traditional Territory.

This is important because of the number of claims brought internationally by investors under FIPA-like treaties that relate to resources. The memorandum points out examples of investor-state disputes against:

a) Moratoriums on gas or mining activities and the corresponding non-approval or freezing of Permits;

b. Refusals of a proposed project such as a quarry or power project following an environmental assessment, public opposition, or the election of a new government;

c. Local opposition to a major project such as a pipeline or waste disposal site;

d. Local opposition, including by indigenous peoples, to resource exploration/exploitation Activities;

e. New laws or regulations on the content of gasoline, exports of hazardous wastes, pesticide use, or anti-tobacco measures;

f. New mining remediation requirements to protect environmental or Native sites;

g. Implementation or revision of rules on power generation, such as under the Ontario Green Energy Act;

h. Hunting and fishing restrictions such as the re-issuance of Caribou tags (apparently as a conservation measure);

i. Reversal of a privatization decision;

j. Expropriation of properties, and

k. New taxes or royalties, such as in the resource sector.

In almost all of these cases, the investor claims that its “right” to make a profit from its investment has been expropriated, directly or indirectly, by a government decision, policy or law. While the FIPA leaves some space for governments to treat aboriginal peoples or firms more preferably than Chinese investors or firms, there is no exception from the sections of the FIPA on expropriation or on so-called minimum standards of treatment.

So the Hupacasath legal case argues:

It is clear that measures taken to preserve land and resources subject to Aboriginal Rights and Title may constitute direct or indirect expropriation, since they may have a significant impact on the value of an investment. Moratoriums on development, restrictions on harvesting or extraction rights, and conditions placed on permits, for example, may lead to a substantial impact on investors. Under the FIPPA, such measures must be accompanied by full compensation, or not enacted at all. Again, this is a significant constriction in the means available to government to protect resources and lands which are the subject of Rights and Title and to settle aboriginal claims.

Not only does the FIPA affect governance by and related to first nations, it will affect the treaty negotiating process itself (the second part of the case). Once ratified, says the memorandum:

Canada’s obligations under the FIPPA will constrain the scope of governmental authority which the HFN will be able to negotiate in any agreement. Because of Canada’s agreement to be bound by the FIPPA, the HFN may be prevented from negotiating any agreement or treaty which protects their rights to exercise their authority in the best interests of the Hupacasath people, including to conserve, manage and protect lands, resources and habitats and to engage in other governance activities, in accordance with traditional Hupacasath laws, customs and practices. The honour of the Crown requires the government to consult with aboriginal peoples prior to assuming obligations which have the effect of limiting the scope of governmental powers which can be negotiated in a treaty.”

I’ve cut out huge parts of the picture here, a lot of it from the jurisprudence backing up the duty to consult not only where Indigenous communities will be directly impacted by a project, law or decision but also, as Underhill argues, “when a government decision has no immediate or direct impact on an asserted aboriginal or treaty right, if that decision may lead to a change in the scope of the Crown’s future discretion to deal with lands and resources subject to Aboriginal Rights and Title claims.”

The Hupacasath have asked the court for:

1. a declaration that Canada is required to engage in a process of consultation and accommodation with First Nations, including the applicant, prior to taking steps which will bind Canada under the FIPPA,

2. an order restraining the Minister of Foreign Affairs or any other official or representative of the Government of Canada from sending a letter to the People’s Republic of China stating that Canada has completed the internal legal procedures for the entry into force of the FIPPA, until the appropriate consultation and accommodation has been carried out; and

3. an interlocutory injunction restraining the Minister of Foreign Affairs or any other official or representative of the Government of Canada from sending a letter to the People’s Republic of China stating that Canada has completed the internal legal procedures for the entry into force of the FIPPA, until this application has been heard and determined by the Court.