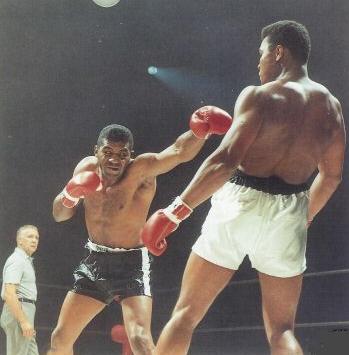

“Come on, American! Come on, white American!” Muhammad Ali was taunting Floyd Patterson, faking punches, dancing around the ring, fighting in what A.J. Liebling once described as his “skittering style, like a pebble scaled over water.” It was November 22, 1965 and Ali was getting back at Patterson, an African-American, for the things Patterson had been saying about him. And he was doing so in spectacular fashion. “Like a little boy pulling off the wings of a butterfly piecemeal,” wrote Robert Lipsyte in the New York Times the next day, “Cassius Clay [as Ali was still being called by many members of the press] mocked and humiliated and punished Floyd Patterson for almost 12 rounds.”

Patterson was no real match for the blindingly quick and prodigiously skilled Ali, but Ali eschewed knocking him out, choosing, instead, to carry Patterson and make him pay for the personal slights. “His intention was humiliation, athletic, psychological, political, and religious,” wrote David Remnick in King of the World: Muhammad Ali and the Rise of an American Hero. “In the clinches he called him Uncle Tom… white man’s nigger.”

When the ref finally stopped the bruising beating in the twelfth round, Ali, retaining his title as Heavyweight Champion, left the ring amidst the crowd’s booming boos. They were astonished by what appeared to be little more than a display of needless cruelty directed at Patterson, a sensitive boxer nicknamed the Gentle Gladiator.

One book about Patterson’s life, by Alan H. Levy, was entitled Floyd Patterson: A Boxer and a Gentleman. Writing for the now-defunct magazine, Nugget, a rival of Playboy magazine, the esteemed novelist and essayist, James Baldwin, estimated that “Patterson, tough and proud and beautiful, is also terribly vulnerable, and looks it.” As an Olympian staying in host country Finland, Patterson was so disturbed by the sight of poor and hungry Finns that “[h]e began helping himself to extra food, which he’d pass on to Finns he’d meet on the street.” He wouldn’t train at the same gym as one boxer because the opportunity to see his opponent train “would give him an unfair advantage in the fight.” Helped by New York Post columnist, Milton Gross, Patterson wrote a deeply introspective and searching autobiography, Victory over Myself, in which he discussed his painful childhood, his shyness, and his insecurities. His confessional and his tendency to dig too deeply and too openly into his own psyche inspired some reporters to call him Freud Patterson. He was considered weak — at least for a boxer. “Compassion is a defect in a fighter,” Jimmy Cannon, the celebrated sports columnist, once wrote about him.

This is the character one begins to see at the centre of W.K. Stratton’s new book, Floyd Patterson: The Fighting Life of Boxing’s Invisible Champion. “Floyd avoided stare-downs with his adversaries,” Stratton writes. “In fact, he could not even bring himself to look them in the eye in the moments leading up to the first round.” So susceptible to shame and embarrassment, he took to wearing disguises — a fake beard, a hat, shades — after losses (after his first defeat to Sonny Liston, he flew to Madrid and, to throw people off even further, he faked a limp). The sports columnist, Jim Murray, called him an “essentially sad and gentle human being.” Speaking to Gay Talese for an Esquire profile about himelf, entitled “The Loser” (a title chosen by the editors, to the disapproval of Talese), Patterson revealed something few boxers would ever admit — if they even felt this way at all. “I have figured out that part of the reason I do the things I do,” Patterson said, “and cannot seem to conquer that one word — myself — is because… is because… I am a coward.” When he was set to fight Eddie Machen, who was diagnosed as having acute schizophrenia and was committed to an institution after he threatened suicide, Arthur Daley of the New York Times called the two “a pair of emotionally entangled men with enough psychoses and neuroses to have fascinated Freud.”

But this gentle man would not pull punches when he set himself against Ali. The war of words between the two titans began in biting earnest more than a year before their battle in the ring. Patterson condemned Ali’s membership in the Nation of Islam, an organization that preached the superiority of Black Muslims and advocated the separation of the races. Patterson clarified his views at length in an essay entitled “I Want to Destroy Clay”, written with Milton Gross, for the October 19, 1964 issue of Sports Illustrated. Insisting on calling Ali by his old name, he wrote that “Clay is so young and has been so misled by the wrong people that he doesn’t appreciate how far we have come and how much harm he has done by joining the Black Muslims. He might as well have joined the Ku Klux Klan.” Patterson, in contrast, believed in the integration of blacks into what was then exclusively white society, and he supported the NAACP’s efforts to open American society up to the nation’s most marginalized community. He took the differences between them seriously enough that he believed beating Ali would be his “contribution to civil rights.”

“I say… that the image of a Black Muslim as the world heavyweight champion disgraces the sport and the nation,” he wrote in another essay for Sports Illustrated, published just six weeks before their fight. “Cassius Clay must be beaten and the Black Muslims’ scourge removed from boxing.” Even Martin Luther King Jr. took a side. “When Cassius Clay joined the Black Muslims,” he said, “he became a champion of racial segregation and that is what we are fighting against. I think perhaps Cassius should spend more time proving his boxing skill and do less talking.”

These comments incensed Ali. He called Patterson the “Black White Hope”. What drew Ali to the Nation of Islam was what he saw as its then-revolutionary insistence that black people were not inferior, that they deserved recognition, and that the promises of civil rights reform were fundamentally hollow when blacks were still looked upon as second-class citizens. Ali couldn’t accept Patterson’s response to what Remnick called the “accumulated slights of mid-century American apartheid.” “Patterson yearned to prove himself worthy of integration,” wrote Remnick. Describing the line of reasoning held by some, he added that: “[T]he white man, in Ali’s rhetoric, did not deserve integration after all he had done to blacks.” So Ali practiced outright defiance, opposing a society which often set itself as a moral judge against which blacks must always appeal. “I don’t have to be what you want me to be,” he once said. “I’m free to be what I want.” What “he didn’t have to be,” Robert Lipsyte clarified, was “Christian, a good solider of American democracy in the mold of Joe Louis, or the kind of athlete-prince white America wanted.”

In an interview for Playboy conducted by Alex Haley, author of Roots: The Saga of an American Family and co-author of The Autobiography of Malcolm X, Ali let loose. “It’s going to be the first time I ever trained to develop in myself a brutal killer instinct,” he said, talking about his upcoming fight with Patterson. “Fighting is just a sport, a game, to me. But Patterson I would want to beat to the floor for the way he rushed out of hiding after his last whipping, announcing that he wanted to fight me because no Muslim deserved to be champ. I never had no concern about his having the Catholic religion. But he was going to jump up to fight me to be the white man’s champion.”

Later, he said “I want to see him cut, bruised, his ribs caved in, and then knocked out.” And, his love of rhyme and doggerel showing: “I’m going to put him flat on his back/ So that he will start acting black.”

And there were many who wanted just that. Years earlier, leading up to Patterson’s fight against Sonny Liston, the poet LeRoi Jones (who would later change his name to Imamu Amiri Baraka) condemned what he took as Patterson’s need for acceptance and approval from whites and called him an “honorary” white man. Baraka saw Patterson as doing the work of the American establishment and as representing a certain tendency to shy away from trenchant critiques of America’s treatment of its citizens. “And each time Patterson fell,” Baraka once wrote, “a vision came to me of the whole colonial West crumbling in some sinister silence.”

In his autobiography, Malcolm X also heaped scorn on Patterson. “Nothing in all the furor which followed was more ridiculous than Floyd Patterson announcing that as a Catholic, he wanted to fight Cassius Clay — to save the heavyweight crown from being held by a Black Muslim,” he wrote. “It was such a sad case of a brainwashed black Christian ready to do battle for the white man — who wants no part of him.”

In his admittedly well-researched book, Stratton, however, articulates a near-complete ignorance of this debate within the black community. He reveals an unnerving tendency to depict those who are simply more cynical about mainstream American society than Patterson as being radicals, and as being vaguely sinister and dangerous. To Stratton, they are “radicalized young African Americans,” while the writer Eldridge Cleaver’s views are quickly framed for the readers by Stratton’s description of him as a “black radical”. In an astonishing passage, Stratton betrays a Manichean, black and white, understanding of the strains of thought produced by black intellectuals. “He [Patterson] was a staunch anti-Communist, supported the war in Vietnam, believed in Martin Luther King Jr.’s nonviolent approach to social change,” writes Stratton, “while younger, more revolutionary blacks thought that the time to pick up the gun had arrived. As a result, many politicized young black Americans joined Muhammad Ali in attacking Floyd as an Uncle Tom.” One gathers from this, it almost goes without saying, that if you do not share Patterson’s views, you must be in the process of firing an automatic weapon.

Stratton writes very little about Patterson’s support for the war in Vietnam. He mentions, in passing, that Patterson maintained this support even after many liberals had taken to condemning the war. He does not mention that Martin Luther King Jr. had come to criticize it, inspiring him to call the United States “the greatest purveyor of violence in the world.” Nor the fact that King was inspired to do so after Ali refused to be drafted into the war in 1967 and after he began to see how much Ali lost (the heavyweight title, and his license to fight — a revocation which would last three years during his prime) by doing so. Ali and Patterson’s differences over Vietnam tellingly reflect their differences about race.

“I feel that if a man lives in a country and enjoys the fruits of the country,” Stratton quotes Patterson as once saying, “he should be willing to fight for it. Clay should serve his country. If not, he should go to jail or be driven out of the country.” This was the seemingly patriotic stance; a stance which accepted American society as it is; a stance Ali could not help but reject. Ali’s “courageous defiance of American power,” as the philosopher Bertrand Russell put it in a letter to Ali, was diametrically opposed to Patterson’s acquiescence. Patterson was either unaware of the fact that the Vietnam war was unjust and brutal and little more than an exercise in neo-imperialism, disproportionately employing, and killing, African American soldiers; or he was precisely the sort of figure Ali and others described: passive and accommodating, the good citizen, the unchallenging citizen. Stratton does not explore these themes deeply enough in his disappointing book about Patterson. What is supposed to be an analysis of one boxer’s remarkable life turns out to be only an extensive catalogue of events (for how can one possibly understand a man if he does not also understand those whose views differed from his?).

Our attempt to understand Patterson’s approach to these issues is better served indirectly. The Olympic Project for Human Rights (OPHR), which organized black athletes, was in the middle of calling for a boycott of the 1968 Mexico City Olympics if certain conditions were not met. These included the resignation of an International Olympic Committee chairperson who had made comments considered racist; the exclusion of South Africa and Rhodesia from the games because of their apartheid system; and Ali’s reinstatement as heavyweight champion “as a symbolic gesture to our gratitude for the stand he took.” When two African Americans named Tommie Smith and John Carlos won medals for the 200-meter race, their particular symbolic gesture embedded itself in the world’s memory. Atop the podium, the Star Spangled Banner playing, they raised their firsts, wearing black gloves (representing black pride and power) in support of the OPHR. A few days later, George Foreman, who Ali would defeat in 1974’s “Rumble in the Jungle”, won the gold medal and, in what was certainly an effort to denigrate the runners and what they stood for, waved an American flag and shouted “United States Power”. Ali watched this on television and it’s quite possible it brought to his mind memories of Floyd Patterson.