As the Canadian labour movement stumbles from defeat to defeat in this crisis period it is worth asking why this is the case. What accounts for the trade union movement’s inability to mount an effective political resistance to austerity? Is it the poor and unimaginative leadership? Maybe it is the ossified and inward-looking culture of trade unions? Is it the poor objective conditions of the crisis? Or perhaps it is the culture of docility and defeatism amongst rank and file members resulting from the regular drubbing the working class has taken over past two decades that explains the current state of labour?

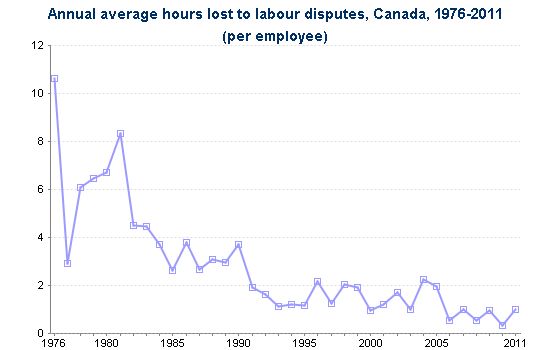

While all these explanations contain a kernel of truth, I think they miss a key element in explaining why the trade union movement has become a paper tiger. The objective conditions for the left and the labour movement in Canada are far from ideal. Over the last 30 years governments and employers have become increasingly emboldened in their anti-union tactics. The neoliberal assault on working people has seen the rollback of social benefits and the power of unions. The changing nature of work in Canada and the restructuring of the global economy has put labour on the back foot — one need only to look at the fall off in strike activity to confirm this. Add to this the depreciation of the U.S. labour movement and this goes a long way in explaining the weakness of the Canadian labour movement.

However, we should be very careful about subscribing to an explanation of labour’s current predicament as primarily a function of unfavourable objective conditions. This view can too often be used as an excuse by labour leaders and other leftists to make peace with the status quo through various forms of collaboration or resignation from struggle. Yet, we cannot just hunker down and simply weather the storm of the crisis waiting for things to magically get better. That is a fantasy.

The truth is that the explanation for labour’s weakness is much more complicated. Yes, labour leaders share some of the responsibility for labour’s recent defeats. Yes, the bureaucratic structures of unions have been more than problematic in stifling creative and strident rank and file activity. But simply locating the problem at the level of bureaucracy is in effect mirroring the explanation put forth by some of the most regressive labour leaders; it is the bad economy, it is external conditions. We should not expect structural reforms and rank and file radicalism to benevolently flow downwards. There is a real danger in having a persecuted mentality if we simple think that the problems facing trade unions are the result of corrupt labour leaders and bad economic conditions. Undoubtedly there is a lot of truth in that analysis, but it more often than not serves as a deflection

The problem with the objective conditions explanation is that it only goes so far. The labour movement in North America was in many ways facing a much worse set of problems in the early 1930s. Unionization rates were minuscule and unions were primarily organized along craft lines, making them fairly conservative. The Great Depression created seemingly impossible conditions for workers to organize and push for gains in their workplace. However, over time, workers did organize industries that were previously impervious to unions, such as auto, and small unit service industries with multiple employees, such as trucking.

This was made possible by the growth of active rank and file networks within workplaces. Successful and strategic organizing drives in key industries such as trucking, rubber, shipping and auto were built from the shop floor up. An active rank and file using creative tactics on the shop floor and in the broader community was what made working class gains possible. It was the rank and file pushing up against the existing labour movement that drove labour leaders and the union movement to adopt a more militant and effective stance.

The question we should be asking is what accounts for vibrant rank and file networks and movements? The conditions of struggle were certainly different in the 1930s than they are today (though not as much as we would like to think). For instance, the working class was less fragmented geographically within cities themselves. But explanations such as this miss the most important factor: the activity and orientation of the left.

Far-left militants, communists, trotskyists and fellow travellers, were the key driving force in building and sustaining rank and file organization that achieved substantial gains for the working class. This was not something that was unique to the old left of the 1930s and 1940s, but can also be seen in the rising workers militancy in the 1970s and early 1980s in Canada.

The far-left, for a variety of reasons has largely abandoned a practical orientation towards workers’ movements in Canada over the past twenty years. Largely this is a capacity question, membership in far-left organizations has dwindled and thus there is an organizational inability to carry out a concerted strategy within workers movements. Implicating oneself in workers’ movements is hard, unsexy work that requires time, resources, and patience. It is the type of work that only really produces results in the long-term and thus only groups with a long-term sense of struggle can engage in it.

The Canadian far-left since the mid-nineties has largely shifted away from organizing long-term strategic struggles. This shift, when coupled with the sustained attack on working people in the neoliberal era, has resulted in ossified unions, weak rank and file movements, concessionary contracts and emboldened state action in support of employers.

Of course, rank and file networks continue to exist and organize. For instance, in Nova Scotia the paramedics in the Local 727 of the International Union of Operating Engineers rejected three contract offers from their employer, EHS. Two of those were in defiance of their own union’s recommendation. This was done through a loose rank and file network that extends across the province. Rank and file paramedics, many of whom were shop stewards, also self-organized pickets across the province to protest the NDP’s stance and EHS’ inability to move at the bargaining table. While the paramedics have had their right to strike taken away, they continue to organize which may result in industrial action if they see no results through arbitration.

In Ontario, the Rank and file Education Workers of Toronto (REWT) were active in organizing the fightback against the Liberal government’s Bill 115. REWT and informal networks that have yet to be consciously-organized, were key in pushing the OSSTF to not just passively accept Bill 115. While REWT was Toronto-based it reflected broader sentiments that existed in the OSSTF outside Toronto. A number of OSSTF districts were critical of Ken Coran’s leadership during the Bill 115 fight, rejecting tentative contracts against Coran’s wishes and forcing the union to follow ETFO’s lead in escalating its tactics. OSSTF districts and members even organized to help humiliate Coran’s election bid as a Liberal in the London West provincial by-election. REWT is currently looking to expand its network across the province and link up with the networks of dissidents across the province and across union lines.

There is a role for the left to play in this current moment of rank and file reconstitution. Left wing organizations should be offering their energies, capacities and analysis while also humbly recognizing and understanding it is a learning process for the far left. This does not mean whole-hearted agreement with every step, but it does mean making engagement with rank and file movements a strategic priority. It also means we need to encourage, facilitate and organize rank and file activity where it does not exist.

It is important for left-wing activists to have a nuanced understanding of the problems facing the labour movement. It is not a matter of simply railing against labour leaders or writing off the union movement’s weakness as a product of the bad economic conditions. We must understand our own responsibilities. If we are serious about challenging capitalism and injustice in Canada and winning real gains for working people the left must organize itself in manner that can orient itself to building and enriching rank and file movements. This means we must build organizations capable of sustained political struggle that connects anti-capitalist and left militants within the workplace.

While this may seem like a herculean task, it only takes a few successful and well-organized rank and file movements to change the mood of large sections of the working class. Confidence is infectious.