Ten years ago today somewhere between 15 and 40 million people around the world participated in a global day of action against the Iraq War. February 15, 2003 was the largest coordinated protest in the history of humanity.

rabble.ca, as it happens, is the same age as the War on Terror, and from the first signs of the Iraq War more than a decade ago we’ve been sharing anti-war voices from across Canada and around the world. Today, we’re featuring an article by Toronto anti-war activist James Clark on the experience of Feb. 15 2003 in Canada.

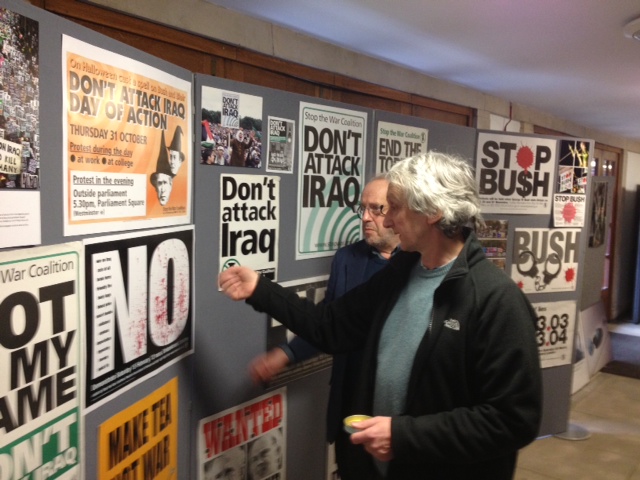

Last weekend, I attended and spoke at an international conference in London, hosted by the Stop the War Coalition UK, assessing the legacy of this unprecedented protest. Here, you can watch the remarks I shared with the conference’s closing session, along with other international guests. The Stop the War site has more video from the conference, as well as a collection of the most important articles assessing the protest anniversary.

Of course one lesson of Feb. 15 2003 is that there are limits to even the most superb displays of anti-war sentiment. The war went ahead despite unprecedented opposition. That shouldn’t be taken as a knock against anti-war organizers per se; it’s the fundamental problem of political power. Mass social movements can only do so much; the rest is a question of the balance of forces in society and its reflection in terms of who holds political power. This is the hardest challenge of all, not unique to the anti-war movement — how to remove and replace right-wing, warmongering governments.

The fact that the war happened despite the largest protests in history can lead to reductive, facile dismissals of the entire anti-war movement, or to radical analyses conducted in a holier/Marxier-than-thou way, diagnosing and/or condemning problems from an outsider perspective. This is symptomatic of a larger problem in the practise of a certain kind of ‘left’ politics where small, self-declared “parties” or tendencies hold themselves aloof from, or above, movements, approaching or joining them only on cynical or even predatory terms. At best, this kind of sectarianism contributes nothing to the vital project of countering pro-war media and politicians; at worst, groups carry out “smash and grab” style interventions, splitting coalitions while trying to recruit young activists into their puritanical parallel political universes. (Pardon this aside: we endured some rather surreal variations on this destructive sectarian behaviour in Vancouver’s anti-war movement.)

In Canada, the movement succeeded in adding to the massive pressure coming from within the Quebec wing of the then-governing Liberal Party, and this contributed to Jean Chretien’s decision not to join the invasion of Iraq. Chretien, however, found more subtle ways for Canada to help the U.S.-led war effort, and added additional troops to the occupation of Afghanistan.

It took a long time, and a lot of hard work, in the years that followed 2003 to turn the tide against Canada’s continuing role in NATO’s occupation of Afghanistan. And while the anti-war movement has “succeeded” in the sense of having public opinion generally on its side, it’s been hard to mobilize numbers in the streets anywhere comparable to 2003 for Afghanistan, let alone for Haiti, Libya, Mali etc.

So, as the war machine rolls on, there is an urgent need for a more visible anti-war movement to take on Stephen Harper’s foreign policy.

Worldwide, neoliberal austerity measures and the emergency of climate change both deserve to be met with coordinated protest on the same scale as February 15, 2003. The anti-war movement has a role to play here, both through the example of its past mobilizations and in terms of joining forces with existing networks.

The issues are related. The trillions currently squandered on war and militarism need to be urgently redirected to meet human needs and to confront the climate emergency. Past generations called for the turning of swords into ploughshares; today, we must turn fighter jets and drones and all the money consumed in producing these ever more sophisticated killing machines into green jobs and into alternative, non fossil fuel energy sources.

Here’s hoping that, ten years from now, Feb. 15 2003 no longer stands as the largest day of protest in human history.