Twenty-six distinct photos in black and white. Scenes of a ravaged city and the human beings within struggling to exist, let alone to find hope for the future. Gravestones of rubble. Homes looted, trashed. Civilians defending their country. Children aged beyond their years by the horrors they’ve lived.

Hagop Vanesian, a 44-year-old Syrian-Armenian photographer from Syria’s largest city, Aleppo (Halab), was meticulous in his choice of photographs for the exhibition, “My Homeland,” which opened at the United Nations Headquarters on January 8 and closed January 16.

“I chose the photographs showing the destruction, and children. I have many photographs of children, maybe 25-30 per cent are of children, these little angels suffering. They are innocent, they don’t understand about politics, they suffer a lot.”

Vanesian, a silversmith by trade, started taking photos 12 years ago, and very early on started documenting his city, building by building.

“Before the war, I was doing documentary photography all over Aleppo. Everyday, I took my camera and photographed people, how they were living,” Vanesian said. “When the war started, I decided to document it. It was very hard at first. For the first couple of days, I couldn’t take a single photograph. This was my birthplace, where I grew up. I have memories there, but even my memories were destroyed, especially in Old Aleppo.”

Iman Tahan, from Aleppo, spoke of her feelings after seeing the photos. “These photos, I wish they weren’t real, I wish nothing like this had happened to my country. I remember every street in these photos. I feel so sad, a lot of memories there.”

One of the memories she spoke of was the murder of her father, in his home, by terrorists.

“We have a well in our house, and since there’s no water — because the ‘rebels’ broke the pipes — my father was giving water to neighbours. He was in his house when a sniper entered the garden and shot him, killed him. Those ‘rebels’ don’t represent the Syrian people. Syrian soldiers aren’t fighting against normal people, they’re fighting against people equipped with the most advanced weapons and trained just to come to Syria. They destroy our homes, churches, mosques. But what makes me happy, our people, because they love Syria so much, decided not to leave. Even my dad, he knew he lived in a very dangerous area, but he decided not to leave, and he paid for it with his life.”

Narrating to those around him, Vanesian explained the significance of and story behind each photo. Of one photo, a smiling woman holding a photo of a young man, he said: “When she saw me photographing, she started to cry. She said, ‘please, don’t photograph this, let us remember Aleppo as it was.’ Then she asked me to photograph she and her son. From her purse she took a photograph of her son, with a big, proud smile. Her son was martyred. Brave woman, Syrian woman.”

For Vanesian, the stories behind the photos need to be told. “Some photographers have come and taken photos, stayed one week, two weeks…They photographed the camps, photographed the war from the other side. Maybe they got more powerful photographs than me. But what I got, I got the stories of the people. Because I lived there, I suffered like them. As they were living, I was living. Without water, without electricity.”

Until about eight months ago, Vanesian was living the life of an average Syrian in Aleppo, except that he was also documenting it.

“One day, I was walking in the Old City, drinking sahlab (made of milk, with cinnamon),” he said. “After I finished, I threw my cup on the ground…there was no trash can. I saw a child, maybe four years old, pick up the cup and start licking the remainders of the sahlab. I couldn’t bring myself to photograph him. When I saw this child licking my cup, I thought, ‘where is the humanity?’ I can’t forget him.”

Pointing at his photographs, he noted two “residential graveyard” photos: one, a group of children and women sitting amongst the gravestones, and the second, a young girl standing near a tombstone.

“Residential areas in Aleppo, and children’s playgrounds, have turned into graveyards. The tombstones of these graves are made from stones from collapsed buildings. I asked the girl in the second photo, ‘What are you doing?’ It was a snowy day. She said she wanted to know where they were going to put the body of her aunt, she wanted to see the place.”

Regarding the photo of a sombre-faced boy, dressed in a suit jacket for ‘Eid holiday, he commented: “That boy, his father is kidnapped, his mother killed. He’s living with his aunt, near the front line of the fighting. Did you see his eyes? I didn’t find any children smiling. They’ve lost their smiles.”

Other photographs show the expected bullet-ridden walls and bullet-shredded metal doors, including one photo with two children, likewise sombre-faced, standing next to a warped metal door.

“If you look closely at the children’s eyes, you see the anger. They’re not smiling, they’re like adults. They grew up, they saw what adults see. They’re around 10 and 13 years old. Before, children in Syria were smiling, but these last few years, you don’t see that. They will need psychological treatment in the future. The psychological damage is worse than the physical damage.”

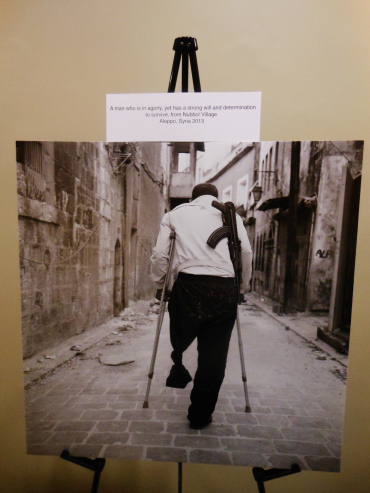

One particularly poignant photograph — a man with one leg missing, on crutches, gun slung over shoulder — shows the determination of the man, reflects the determination of Syria, to fight back and survive.

“He’s defending his neighbourhood in Aleppo, but actually he was displaced from Nubool, the village where he lost his leg during fighting. He is still fighting, even with one leg. He will fight to the end,” said Vanesian.

Two photos of homes looted and destroyed, one Christian, one Muslim, speak of Syria’s multi-religious fabric, that most Syrians I’ve spoken with maintain was never sectarian.

“I intentionally put these photos side-by-side. It’s not only Muslim houses that are looted, Christian homes are too. They don’t differentiate, doesn’t matter whose house, they’re going to loot it.”

Unsurprisingly, the anti-Syrian group, the so-called “National Syrian Coalition” issued a letter accusing the exhibition as being propaganda, and calling for the display to be shut down.

Syrians attending the exhibition felt otherwise.

Rana Nasrallah, a Syrian from the predominantly Druze city of Sweida, now living in New Jersey, was among Syrian expats attending the exhibition.

“Each picture talks, speaks of the different problems in Syria. These photos show the truth exactly as it is in Syria. I was in Syria a month and a half ago, I saw with my eyes. I had a good life there. I feel broken for what has happened to my country.”

Fadi, from Midan, what he describes as a mixed Armenian-Muslim area of Aleppo near the front line of the fighting, agreed that the exhibition was representative of the reality.

“One hundred percent, the photos tell the truth. I’m Muslim. We never had any sectarian problems. We lived together, doesn’t matter what you believe, who you pray to. Now…”

Al-Akhbar and al-Mayadeen correspondent Nizar Abboud attended, reporting on the exhibition but also pointing out the need for such an exhibition. “The world is hearing one point of view on Syria, and this is not by coincidence. I think this is premeditated. Also, there is self-censorship in the media, including my colleagues who work at the United Nations. They like to play the tunes those who pay them would like to hear. “

Earlier, in a private interview, the Syrian Ambassador to the UN, Dr. Bashar al-Ja’afari — who organized and attended the exhibition — told me: “For four years I have been trying very hard to do something inside the UN. Every time we attempted to do something, we were confronted by a huge amount of bureaucracy and excuses.” He, too, said the intent of the exhibition was not political. “It’s about Syria and the Syrian people. It’s about what happened in Aleppo, through undeniable photos. Any honest, objective Syrian who loves his homeland should have a great interest in showing what is going on in Syria. All Syrians should push for organizing more exhibitions, not only at the United Nations but all over the world.”

One of the accusations thrown at Vanesian is that he had photographed only from areas where the Syrian army was present.

“I photograph the front lines, so I need protection, like most photojournalists in areas of war. Transportation is no longer safe in Syria. Some of my friends and relatives have been kidnapped and we haven’t heard about them for over a year.”

That said, Vanesian took risks with many of his photos, including one shot from the side of the terrorists, unbeknownst to their snipers.

“Most front line lanes are covered with fabric, to block the view of snipers and prevent them from shooting the other side. When I took this photo, my back was to the snipers, but I was hiding behind a stone. The other side of the fabric is the safe area, but I came to this side to take the photo. If I had moved my head, I would have gotten shot. If you put your finger up, they’ll shoot right away.”

Vanesian maintains that his objective is solely humanitarian.

“I’m not doing this for political reasons, I just take the photos to let people see what is happening. With my photographs, I just want one thing: for people to remember there are people suffering in Syria. Just let them think, for a moment, about the suffering. I can’t bring back Aleppo as it was. I lost it, as I lost friends, relatives…I can’t bring my city back. The market in Aleppo was the longest enclosed market (in the world). It is burned completely. The destruction of Aleppo is a shame for humanity. The heritage has been destroyed; it belongs to all the world.

All those people in my photos, I didn’t just click the shutter, didn’t just take their photographs, I got their stories. I didn’t make money from their photos. I wanted to show these photos for humanitarian reasons, nothing else.”

Hagop Vanesian’s website is: http://www.hagopvanesian.com

All photos by Eva Bartlett