Lovelace was hard to watch. It was hard to be reminded that there was a time when women couldn’t legally testify against their husbands. It was hard to watch a woman trying to escape from an abusive man, but have nowhere to go. It was hard to watch yet another woman’s trust and love for a man be repaid with hatred and violence. But it felt refreshing to see Hollywood deal with the sex industry in a way that didn’t make light of, glorify, or sexualize women’s experiences in it. John Stoltenberg wrote: “cinematic justice has never been so bittersweet.”

Deep Throat holds a significant place in pop culture, pinpointing the beginnings of porn culture. It was seen as fun, sexy entertainment then and is seen more as kitsch today — continuing to be, more often, the butt of a joke rather than a reminder of the brutal reality that is misogyny.

Today, the project of mainstreaming pornorgaphy that began back in the 70s is complete. Hipster culture loves vintage porn. We’ve brought it back via burlesque and pin-ups, as well as in fashion photography. Our larger cultural attitude towards porn is that it’s an ordinary part of life. Objectification is something fun we do at parties, porn is decorative — something we put up on walls or play in the background at parties. It’s something that brave, open-minded, sexually liberal women do. Feminism had something going there for a while in a solid critique of pornography during the 80s (galvanized, in part, by the publication of Linda’s memoir, Ordeal). But we lost the plot on that one, handing porn over to liberals, capitalists, and pop culture.

Feminism has come a long way and so has porn culture. No longer relegated to dark theatres, no longer a subculture or something that’s purely masturbatory — it’s a look.

We’ve all seen enough American Apparel ads to know that grainy, soft core porn style that’s supposed to remind us of the good old days before breast implants and hairless crotches, as though it’s more ethical to objectify women with real breasts. We don’t see it as sexism, we see it as a throwback. Or art. Or irony. Or something.

But hair or no hair, real or fake breasts, the only thing that’s really changed since the 70s, when Deep Throat came out, is that porn has successfully woven it’s way into our everyday lives. It’s our fashion, our entertainment, our celebrity culture, it’s in the bars and at the parties we go to. That the foundation for our current reality was built, in part, on the abuse and exploitation of this one woman, Linda Lovelace, is not insignificant.

Linda Lovelace was called the poster girl for the sexual revolution, if that tells you anything about the sexual revolution… Women really got screwed on that one (pun acknowledged). Informed of our liberation, we became free to become the public, rather than just private, sexual playthings of men. What was different now that we were “liberated” was that we had to like it. We had to be turned on by our own objectification and enjoy whatever male culture deemed sexy. Our own “liberation” was used against us, to shame us into subordination — albeit with smiles on our faces, moaning and groaning in feigned ecstasy.

Most media outlets covered the film with an appropriate level disgust for and critique of the reality of Deep Throat, the popularization of which turned out to be, essentially, a celebration of abuse and exploitation. “This is the Linda that the world didn’t see and who, even as her body became a public spectacle, nursed her wounds in private,” reads a review in The New York Times. How often do male fantasies come at the expense of women’s lives?

In The Week, Monika Bartyzel argues that Lovelace failed to capture the extent of the abuse inflicted on Linda, saying that the directors “frame Chuck and Linda as some pair of doomed, star-crossed lovers by ending on the note that Chuck died exactly three months after Linda on July 22, 2002.” Bartyzel points out that Chuck began abusing Linda and prostituting her even before they were married, though the film shows the abuse beginning on their wedding night when he rapes her. As grim and as upsetting as it was to watch the film, the reality was actually much worse.

Stoltenberg points this out as well, saying:

“The movie makers left out the worst of what was done to Linda, which was abominable and included forced bestiality. Had they not, I have no doubt, Lovelace would have been not only unreleasable but unwatchable.”

Even the most tepid version of reality is almost unbearable.

Gloria Steinem, who befriended and supported Linda when she came out about the abuse and wrote the article, “The Real Linda Lovelace,” for Ms. Magazine in 1980, said something similar after attending a screening of the film — that Linda’s life with Traynor and in porn was much more violent than Lovelace let on.

Yet liberals and even some feminists are unsatisfied with that truth. Desperately clinging to the “empowerment” narrative sold to them first by the porn-makers themselves, back in the 70s, and again by third wave feminism today, they continue the victim-blaming that began so many decades ago, questioning Linda’s credibility and asking why she returned to the industry years later. (Newsflash: she needed the money.) They say, over and over again, that Linda eventually rejected the anti-porn movement years later, as though that somehow compares to or negates the abuse and exploitation she experienced in the industry.

In a rather convoluted review at Art Forum, writer Sarah Nicole Prickett accuses the film of painting Linda as a victim (well, I’m afraid she was), calling it “pro-family, anti-porn-industry propaganda.” Angry at the lack of nuance and the perpetuation of simplistic tropes, Prickett sees the film as, “at surface, a morality play” which falls back on the “happy hooker/sad hooker dualism.”

Prickett’s main source of frustration seems to be that the filmmakers painted Linda as a “good girl.”

“In 1972, Linda found millions of Americans willing to think any woman would believe that her clitoris was in her throat, and in 1980 she entered a world ready to accept that a woman regretted, without complexity, every sex act she’d ever committed. But this year—what gives? Must a heroine still be proven innocent?”

A piece in The Atlantic reminds us that things are oh so different in today’s porn industry — full of fairy dust and ponies. Whatever you do, make Linda’s story the exception, not the rule, the writer warns us.

Somehow, no matter how many tales of abuse and exploitation we hear, no matter what we actually see in the world around us, we are loathe to point the finger at the perpetrator.

The liberals are angry, no doubt. But not at the gang rapes or the beatings inflicted. Rather they’re mad that Linda wasn’t the “sexual revolutionary” society wanted her to be. Mad that she wasn’t the “happy hooker” or the “carefree if drug-addicted superfreak” that would be so much more palatable (and more titillating) on screen.

We’ve learned to look for nuance at the expense of truth. Grey areas and character flaws don’t alter reality to the point where we can’t say that which is glaringly obvious. We remain so uncomfortable with the victimization of women that we look away — pointing towards Andrea Dworkin and vilifying Catharine MacKinnon, women who supported Linda and fought tirelessly against male violence. Whether or not Linda remained a staunch anti-porn campaigner for life doesn’t change her history in porn and her experiences at the hands of abusive men in her life.

Feminism is an easier target, to be sure. And perhaps if you silence the voices pointing out oppression, it will cease to be a reality for you. Of course the privilege of ignorance will never save those who bear the brunt of our collective fantasy.

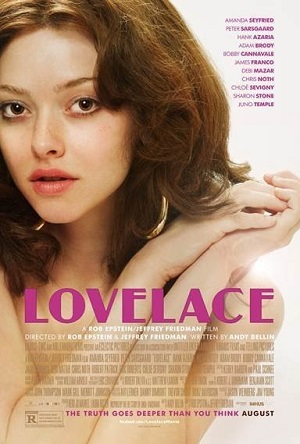

Image: Millennium films