Royal Cinema, Thursday March 21, 2013

Everybody loves the big film festivals because they are perceived as a chance to feel like you are on the inside track for the next big flick. But big festivals are often just a venue for lending cred to films opening on commercial screens the following week. Rarely are you offered real access or insight into what it took to make a film work. But the 2013 Canadian Film Festival is as real as it gets. It’s a true opportunity to catch the next Cronenbergs when they are still crafting shorts on a shoestring. And if young filmmakers’ first festival screenings are your thing, the Student Short program was an edgy showcase of new Canadian film talent.

First on the program was Dedication, a documentary by Brian Gregory. It’s a snapshot of a young photographer trying to shoot his way out of Scarborough with a camera. Languidly shot in black and white, this short is a testament to the transformative possibility that art can be for working-class youth. The narration is direct and unsentimental. Coming from Scarborough myself, I can attest that Dedication, the film, felt viscerally real.

Bluebird is a visual poem by Ariane Lorrain about a modern hippie family who make an old school bus, the Bluebird of the title, their home. Shot in grainy black and white, it’s beautiful and disturbing in turns. The dreadlocked dad plays guitar and sings for the entertainment of his brood. The mother breastfeeds and takes hits off a joint. There is no narration but the story is familiar. This is a family who have opted to live outside of the mainstream in the tradition of Kesey and Kerouac. There is one daughter who seems to come alive when she is skating. Perhaps this is just a respite for her (and the viewer) from the claustrophobic confines of the bus. Perhaps it is just the most normal thing she gets to do. Skating seems so free and pure in contrast to the cramped, wood-heated bus. When she skates, she is the real bluebird.

Flood was the first fictional narrative of the program. Directed by Derek Branscombe, Flood walks the line between realism and horror. The film is a non-linear story about a Korean family wherein a housewife is driven mad by the confines of her own existence. As always with good horror, the devil is in the details. In this case it is a callous husband, a dripping tap, a broken china plate, and, outside her front door, a concrete barrier over which she can see glass towers in which she will never live. In the end, this woman’s madness is directed at her own children. The horror of the movie is powerful because of the familiarity of the story. It is story we periodically see on the news. Flood takes us into the nightmare behind the front door always featured in those news stories.

Zen by Arshad Khan, is a fully-fledged documentary that gently squeezes the heart of the viewer. Zen is a three-year-old boy with cerebral palsy. His father and mother are the picture of a modern Canadian family; he is of Indian Sikh extraction, she from a family of Pakistani Muslims. But her family has rejected her as a “cancer” for marrying outside her culture. Her pain is profound and palpable. This pain is the cradle of her resolve to never to reject her child. Into this young family enters Zen, who because of hypoxia experienced during a difficult birth, was born with cerebral palsy. This is the kind of thing that could easily fracture a family already enduring familial and cultural pressures. But this couple’s love for their boy is limitless. They disregard the advice of insensitive doctors and seek therapies to increase Zen’s quality of life. They educate themselves on nutrition, teach him how to eat rather than feed him through an abdominal tube, and travel to Chile for innovative therapies for their son at their own expense. The scene where Zen’s distress is visibly relieved by his mother playing the bossa nova song “Sway” played on an iPhone is some of the most moving footage I have seen in a documentary. Khan’s exteriors of the Mississauga winter panorama with its windswept emptiness, and cookie cutter subdivisions counterpoints perfectly to the warmth and love inside Zen’s home. And the love depicted was not filmic artifice. Zen and his parents were at the screening, and radiated the love that Khan captured in his film. Meeting them was the kind of privilege one only gets to experience at this kind of festival.

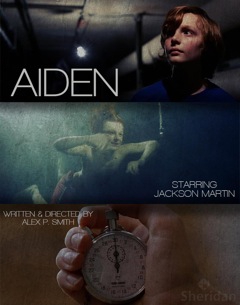

Aiden, directed by Alex P. Smith is the most accomplished narrative of this series. It’s the story of a young boy whose mother tries to allay his nightmares with some advice about facing fear. She tells him that if he spends a minute confronting each of them his nightmares will disappear. He is afraid of the dark and drowning, and she starts his fear list with these. When he returns from school to find that his mother has been killed, he adds death to the list. The rest of the film is the process of Aiden as he takes on his fear of the dark, of drowning, and of death itself. Aiden is an exceptional film on the part of both in its actors and director. The storytelling is concise and visual. It represents the best possibility of film.

If I was going to pick the next Cronenberg out of this crop of directors, Alex P. Smith is the guy.

Now I really can’t wait to catch Alex Boothby’s feature, Mr. Viral, this Saturday night.