To the uninitiated, the crisis in Israel-Palestine seems unbelievably complicated and impossibly difficult to solve. What’s required to understand it is a glance back at some history.

The conflict in Israel-Palestine has its roots in the scourge of anti-Semitism, or hatred of Jews. Anti-Semitism is hostility, prejudice, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such views is called an anti-Semite. Anti-Semitism is a form of racism. The use of the root word Semite in this expression gives the impression that anti-Semitism is directed against all Semitic people. But the compound word anti-Semite was popularized in Germany in the 19th century as a scientific-sounding term for Judenhass, or “Jew-hatred,” and that has been the dominant use of the term ever since.

There is a long tradition of Jew hatred, or anti-Semitism, in Western, Christian society. Christian rhetoric and antipathy towards Jews developed in the early years of Christianity and was reinforced by anti-Jewish measures over the ensuing centuries. Anti-Jewish actions taken by Christians included the expulsion of Jews from England by King Edward I in 1290 as well as their expulsion from Spain by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella in 1492.

Anti-Jewish laws were widespread throughout Christian society. It was not until the reign of Emperor Napoleon Bonaparte in France that laws were enacted emancipating France’s Jews and establishing them as equal citizens of France in the tradition of the French Revolution. In countries that Napoleon conquered during the Napoleonic Wars, he emancipated the Jews and introduced other ideas that arose from the French Revolution. In the process, Napoleon put an end to laws forcing Jews to live in ghettos and limiting Jews’ rights to own property, engage in religious worship, and earn their living in certain occupations.

Despite this progress, anti-Jewish prejudice and practices as well as periodic upsurges in anti-Jewish violence remained common in Europe. In Imperial Russia, the Czarist regime created The Pale of Settlement, a region in the western part of the Russian Empire in which Jews were confined to live. Jews were prohibited from living beyond the boundaries of the Pale. In addition, Jews were excluded from residing in a number of cities within the Pale.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries violent, bloody massacres of Jews living in the Russian Empire, known as pogroms, took place periodically. Other forms of prejudice and persecution against Jews were integral to Russian society.

Different responses to anti-Semitism

There were different responses to this and other forms of persecution within the Jewish communities of Europe. Some sought to build on the progress that had begun in France with the reign of Napoleon, when he ended discriminatory practices by the French government against Jews. Others came to believe that anti-Semitism could not be defeated or cured, and that the only way to avoid it was to establish a Jewish state that could provide a sanctuary for the world’s Jews. Prominent among the proponents of this idea was Theodor Herzl, a late 19th century Austro-Hungarian journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer, who is considered one of the fathers of Zionism. Herzl, an atheist and secularist, rejected the view that was then dominant among Jews, that their emancipation was possible in Europe. He insisted that the Jews must remove themselves from Europe.

Herzl and his followers held the First Zionist Congress in Basel, Switzerland in 1897, where he was elected president. In 1898 he began a series of diplomatic initiatives designed to build support for the creation of a Jewish country.

The bride is beautiful, but she is married to another man

According to a frequently repeated story, during the early years of the Zionist movement a number of European Jews were sent to Palestine to investigate its suitability as a location for a Jewish state. As the story goes, they reported back that “the bride is beautiful, but she is married to another man.” In other words, Palestine is a wonderful place, but it belongs to others.

The point of the story is that even in the early years of the Zionist movement, there was already recognition that it would be unjust and immoral for Jews to try to lay claim to Palestine. Despite this awareness, however, Zionists proceeded with their plans to build a Jewish state there.

How did Zionists deal with the problem posed by the fact that there was an Indigenous population living where they wanted to situate their state? From the beginning, with few exceptions, Zionists were of the view that the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine necessitated the displacement of the Indigenous population that was already living there. There were tactical differences among various parts of the organizations that dominated the Zionist movement as to how this goal was to be achieved. Some hoped to convince the Palestinians to leave willingly; others wanted to buy them out; still others believed in expelling them by force of arms. But all shared the view that the task of ridding the region of its Indigenous population was integral to the creation of a Jewish state.

Although there was general agreement among Zionists that this goal was not to be discussed publicly, David Ben Gurion and other prominent Zionist leaders understood that the compulsory transfer of the Palestinian inhabitants of the region was essential to creating a Jewish state there. The Twentieth Zionist Congress, which met in Zurich in 1937, went so far as to create a Transfer Committee of experts whose task was to look into the practical aspects of the matter.

How Israel came to control all of Palestine

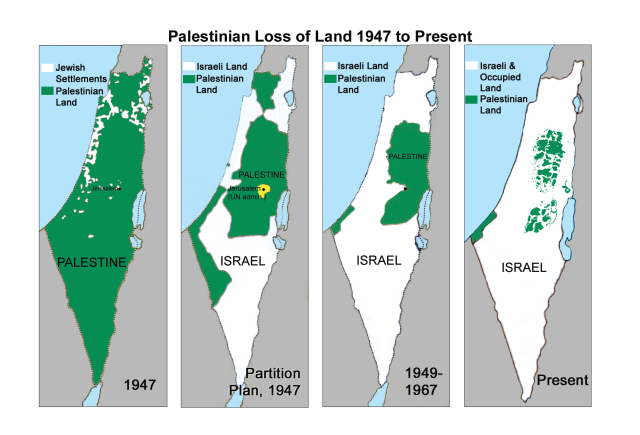

Zionist leaders never lost sight of their goal of annexing the entire region of Palestine. When the United Nations partitioned Palestine in 1947, dividing the territory into a Zionist enclave and a Palestinian one, 55% of the land was allotted to the Jews and 45 per cent to the Palestinians. Although Ben Gurion and his followers made the tactical decision to accept the UN proposal, by the time Israel’s ostensibly defensive war had ended in 1948, the portion of the territory of Palestine controlled by the new Jewish state had increased to 78 per cent.

This territorial status quo prevailed until June 1967, when Israel’s military occupied the West Bank and Gaza, leaving Israel in control of 100 per cent of Palestine. When that war was over, the Israeli cabinet agreed that there would be no return to the prewar borders.

Since that time, Israeli governments of all political stripes have increased the Jewish population of the occupied territories by encouraging the creation of settlements. Hundreds of thousands of Jewish settlers now live in the Occupied Palestinian Territories, using ever-increasing amounts of the area’s water. Not surprisingly, the brutality of the occupation and its attendant policies have generated significant Palestinian pushback, ultimately leading to a series of rebellions and other forms of resistance against the occupying forces. But rather than reconsider its occupation, which is deemed illegal by the United Nations and the International Court of Justice, the Israeli response has been to mount periodic military assaults against the civilian Palestinian population and to administer an increasingly repressive regime of military occupation on a permanent basis.

Contemporary analogies elsewhere in the world

If the Jews who came to Palestine had come as refugees willing to live in peace and harmony with their Palestinian neighbours, I think their position would have been understandable and defensible. In fact, I think that there is a possibility that they might have been welcomed on that basis. But it is difficult to imagine any population welcoming a population of settlers bent on displacing them from their homes.

By way of contemporary analogy, we have welcomed thousands of Syrian refugees fleeing the horrors of war in their country. But how would we react if these refugees began to insist upon their right to displace those of us already living here in the name of some kind of Syrian nationalism and embarked on the process of creating a Syrian state in Canada?

I’m sure that all this sounds very familiar to our Indigenous sisters and brothers. As the victims of ethnic cleansing, genocide and residential schools, they have no difficulty in understanding the difference between sharing their land with people interested in living with them as neighbours and being beset by those who see them as a problem that must be eliminated.

In Canada, we have taken some preliminary, if inadequate, steps in the direction of rectifying the crimes that we settlers have committed against our our Indigenous sisters and brothers. Clearly there is a huge amount still to be done. But the path to resolving the crisis is clear. The first step involves acknowledging what we settlers have done to the Indigenous peoples of Canada. The second step involves negotiating reparations and other policies designed to undo the damage that we have done them.

I would argue that the same approach should be followed to resolve the conflict in Israel-Palestine. First, there must be an acknowledgement of the crimes that have been committed against the Palestinian people. Then there must be an effort made to provide the Palestinian people with reparations and other means of addressing the damage that has been done to them.

The government of Israel isn’t interested in ending the crisis

Clearly, the government of Israel and those who support what it is doing to the Palestinians do not share this view. Rather than acknowledging the crimes that have been committed by Israel against the Palestinians, the government of Israel resists any and all attempts to rectify the situation.

It has even gone so far as to pass a piece of legislation called the Nakba Law. (Nakba is the Arabic term referring to the events of 1948, when hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were forcibly displaced from their homeland by the creation of the state of Israel.) The Nakba Law makes it illegal for anyone to reject Israel as a Jewish state or to mark Israel’s Independence Day as a day of mourning.

So what should we do in the face of Israeli intransigence? In my view and that of the organization I represent, Independent Jewish Voices Canada, we should follow the lead of Palestinian civil society, which issued a call in 2005 for the world to engage in Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions against Israel until Israel meets its obligation to recognize the Palestinian people’s inalienable right to self-determination and fully complies with the precepts of international law by:

1. Ending its occupation and colonization of all Arab lands and dismantling its Separation Wall

2. Recognizing the fundamental rights of the Arab-Palestinian citizens of Israel to full equality; and

3. Respecting, protecting and promoting the rights of Palestinian refugees to return to their homes and properties as stipulated in UN resolution 194.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.