In part one, last week, I started this discussion by looking briefly at the state of social assistance in Ontario (which, in its obvious inadequacy, I take to be more or less representative of social assistance nationally) and the relationship between food and economic (in)security. Today I consider:

Why do low income families eat less healthy food?

It’s hard to say why exactly this negative relationship between income and food security obtains. (Though a social indicators of health framework is a good place to start.) Neither of the studies I mentioned in part one of this post established a causal relationship between income and nutrition, but there are a range of better and worse explanations. For example, and beyond the obvious point that low income families just don’t have enough money to buy enough good food, many low income families have insufficient facilities to store or preserve lower cost and healthier fresh foods; live in “food deserts,” where there are no real grocery stores; cannot take advantage of bulk savings at large, typically accessible-by-minivan-superstores; and are relatively less “food literate.”

Do poor people know less about food?

I want to spend the rest of this post discussing and unsettling the idea that low income people are relatively less “food literate.”

Food literacy “involves understanding: where food comes from; the impacts of food on health, the environment and the economy; and how to grow, prepare, and prefer healthy, safe and nutritious food.” Elsewhere, the focus is more on how we read and understand food labeling and respond to food advertising. (See more here, and here.)

On the one hand, increasing food literacy seems a wonderful idea. By better understanding the consequences of our actions in a broken food system we are in turn more able to bring about positive change. This worked for the anti-sweatshop movement, right? “There is much to gain by including more information about local food production and procurement in food literacy education, including helping to increase knowledge of local food systems, positively influencing the environmental impact of household food choices and raising awareness about the link between agriculture, food and wellness.”

Maybe even better, food literacy projects allow people–of whatever income–to do more with less. Indeed, a range of people involved in food security/justice/literacy projects emphasize the emancipating potential of teaching people how to turn raw ingredients into healthy meals. The world food superstar Jamie Oliver keeps food literacy at the centre of his advocacy work, and has argued that obesity crises across the so-called First World are “fuelled by lack of cooking skills.”

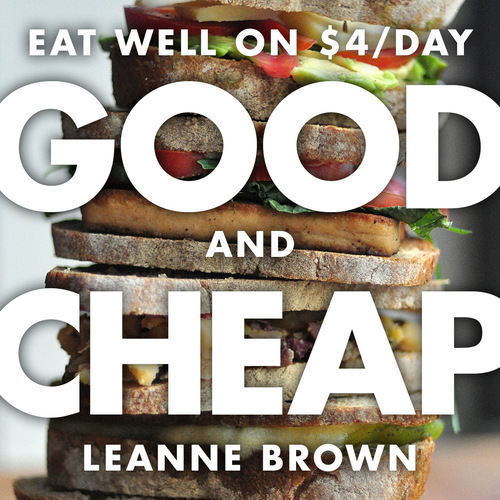

A similar impulse motivates projects like Leanne Brown’s beautiful Good and Cheap cookbook. Her book is full of healthy and delicious recipes that cost about $4 or less–originally it was called “a SNAP Cookbook,” so named because a person living on food stamps could theoretically afford to make her recipes. (SNAP, or the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, is what the US government calls food stamps.)

The cookbook is also free! (Or donate, and she’ll pay it forward.)

Brown’s cookbook is great, and Oliver is not wrong. When people know how to creatively prepare food from scratch, they can eat better food for less money, and should be healthier for it.

However, we should keep two distinct claims separate. Although it’s true that some low-income people have poor cooking skills — are relatively less food literate, let’s say — it is most definitely not true that all low-income people have poor cooking skills. This is true in the same way that some high income folks cook well and often and with other people, whereas other wealthy people don’t. You’re thinking: of course!

Whose fault?

By making food literacy — or lack thereof — the basic issue or explanation for food insecurity, we risk losing sight of larger structural issues while leaning towards a dangerous kind of victim-blaming. As another blogger put it:

It seems like some people are constantly wringing their hands about how poor people eat (to wit: badly.) And the most popularly proposed solution is to teach them (“them”) more about nutrition! Or educate them in general.

Because obviously they just don’t know what they’re doing. And that’s why they eat so badly, and hence, why their health tends to be poorer!

And eureka! — you have a tidy solution that not only absolves financial and economic guilt, but, as a bonus, allows richer, more-edumacated people to assume the role of benevolent experts.

This doesn’t have to be the case, and indeed some of the groups talking about food literacy (explicitly or not) are careful to ask why it appears that certain groups are consistently less food secure, and to make that question part of their food literacy curriculum.

I conclude this series next week by sharing what people living on a low income have said, when asked about food literacy approaches to “solving” food insecurity. (Hint: it might be all about the Benjamins.)

Image: Library of Congress, Mary Post Wolcott