Last month saw the release of two important artistic projects that visualize reproductive choice: the American movie Obvious Child, and the Canadian book One Kind Word.

Half of pregnancies are unplanned, and 40 per cent of these end in abortion. In the U.S. more than a million women have abortions each year, but this is not reflected in mainstream film. As writer/director Gillian Robespierre explained, “We did write this script in response to a slew of movies that came out about unplanned pregnancy that always resulted in childbirth. It was frustrating, and instead of waiting for that movie to be made we decided to make it ourselves. I didn’t want to show the same film where the woman is struggling with the decision — I’ve seen that film before — and it’s not that this didn’t happen with this character, but we didn’t want to show the same story.”

Obvious Child

In 2009 she teamed up with comedian Jenny Slate to make a short film that went viral online. They then got funding to make a feature-length film that premiered at Sundance and was released in theaters last month. Obvious Child (the title of a Paul Simon song used in the film) is a romantic comedy about a stand-up comic who breaks up with her partner, loses her job, then has an unplanned pregnancy — and choses abortion. It has been falsely characterized as an “abortion comedy,” but as Slate said in an interview on CBC, “It’s about this woman’s journey from being passive to active, and learning how to stand by her decisions and still be herself, which means still be funny. Now that she’s making a very adult decision, which is to have this safe procedure, can she still be irreverent and playful? Is her nature still hers when it’s paired with this choice?”

The film follows the conventional story arc of a romantic comedy, is very irreverent and playful when it comes to the main character, but is very normalizing when portraying abortion. The filmmakers consulted Planned Parenthood to provide an accurate portrayal of a clinic experience — from counseling, to the procedure and recovery room. It shows the ongoing fear of stigma and importance of support. Refreshingly, the film doesn’t give a second of screen time to the anti-choice, though it does reference financial barriers and government restrictions.

It speaks volumes of mainstream film that this is one of the few to pass the Bechdel test — two female characters with names, who talk to each, about something other than a man—and rarer still that it be a positive portrayal of one of the million American women each year who chooses abortion. As Slate explained, “In the United States, women’s rights are very much under attack, and it’s enraging to some people to see a woman just make that decision. It’s good to me that the film is ground-breaking in a way, and in another way I look forward to a day when this is just part of a story….I get sent a lot of scripts that I read, and a lot of them have astounding and frankly irritating things that the women are doing — like women being traditionally catty to each other, often written by men. That to me is more shocking than a woman choosing what to do with her body.”

This is just one story — of a 30-year old urban white woman choosing abortion—but it’s an invitation to share others. As Robespierre said in an interview on Democracy Now on the anniversary of Roe v Wade, “Women’s rights are under attack, and there are many states that have put new restrictions on women being able to have safe, positive procedures. I think it’s a really good time for people to tell their stories.”

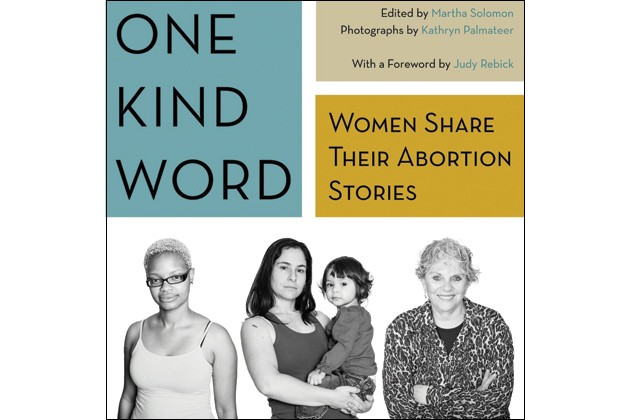

One Kind Word

While Robespierre and Slate were producing their short and feature-length films on abortion, Martha Solomon and Kathryn Palmateer — founders of arts4choice — were gathering stories and portraits of women across Canada who have had abortions. Seven years of work culminated in the launch last month of One Kind Word: Women Share Their Abortion Stories. The title is from the personal story of Lori, a clinic counselor who reflected on her own abortion in 1972: “the support I would have appreciated: one kind word from anyone.”

In Canada there is no abortion law, but there are still multiple barriers to reproductive justice. As Solomon and Palmateer write in the introduction: “The iniquities of abortion access mirror the greater inequities in our society. Colonialism and racism can severely affect women’s abortion access and experiences. Low-income women face greater barriers than do affluent women, and access is even more tenuous for homeless, refugee and undocumented women. In many parts of the country, there are simply no providers available; in others, such as Prince Edward Island, provincial health authorities have refused to honour women’s basic reproductive health care needs and do not fund abortion services. Women from P.E.I. who require an abortion must travel to another province and fund the costs of their abortion and travel expenses themselves. In New Brunswick, a woman must have the approval of two doctors before obtaining a provincially funded abortion. Sadly, the Fredericton Morgentaler clinic, the only other option for women seeking abortions in the maritimes, is scheduled to close in July 2014 after years of fighting the New Brunswick government, further limiting the already paltry options for east coast women. In no other area of health care would such an egregious disrespect for people’s basic health care needs be tolerated. Indeed, the problems with access in Canada point to a deep-seated misogyny within our country and our health care system.”

This extends into medical schools, which have insufficient discussion of abortion except for students who actively pursue abortion training. Marginalizing one of the most common medical procedures, which one third of women will chose at some point in their lives, contributes to the lack of abortion providers — a problem that Medical Students For Choice seeks to correct, as Jillian Bardsley explains in the book’s forward.

Women sharing their abortion stories was part of the last great wave of reproductive justice struggles, and part of the new movement. As Judy Rebick writes in the book’s foreword,

“As part of the movement then, we organized testimonials from women who had desperately sought abortion when it was illegal, or later when it was legalized under such restrictive circumstances that only a small percentage of women who needed abortions got them in safe and supportive conditions. But since the legalization of abortion, there has been too much silence. The anti-choice organizations, who now have a supportive federal government, have continued their vile propaganda, the purpose of which is, at least in part, to make women with an unwanted pregnancy feel guilt if they chose abortion. That’s why I think a book where women go public about their abortions is so important today.”

As Solomon and Palmateer summarize,

“In this book you will meet thirty-two Canadian women who have had abortions. They are courageous and brave; they are inspiring; they are our mothers, sisters, friends, lovers, neighbors, teachers, politicians, doctors, and grandmothers….Our participants come from a range of class backgrounds, ethnicities, abilities, and language groups. You will read stories from Latina women, French Canadians, and First Nations women, as well as women from Asian, Indo-Caribbean, and African Canadian communities. Our participants are young and old (and in-between), financially stable and just making ends meet, mothers and childless, in relationships and single, heterosexual and lesbian.”

These stories cover the history of abortion in Canada — from Linda who had a “terrifying experience” in 1968 when abortion was illegal, to Joyce whose experience with a Therapeutic Abortion Committee in 1988 shaped her life as a pro-choice activist, to Mika who had a clinic abortion four months before she participated in the book. The stories cover a variety of experiences in unplanned pregnancies, barriers to abortion, emotional reactions to the procedure, and level of support from family or friends. Regardless of their personal reactions to abortion — from grieving to ambivalence to empowerment — the women have a shared experience of facing barriers to choice and feeling the need to speak out. As Kaleigh says, about both her disability and her experience with abortion: “In having open conversations we actively annihilate shame.”

The format of written stories (30 in English, one in Spanish and one in French) combined with photos makes an instant human connection to the women and the importance of reproductive choice. As Sheila explains:

“Photos complementing our written stories, particularly a collection of women’s photos and stories like arts4choice is producing (rather than an individual story like mine), is even more dramatic in its effect because the visual dimension will help people see and process more comprehensively that we are everywhere, and we are various ages from different racial, class, and cultural backgrounds. Through the photos, they will see people who look like their friends, coworkers, sisters, etcetera. This association of familiarity will help them feel some empathy, or possibly even a little compassion.”

As Solomon and Palmateer conclude:

“It is time for women themselves to articulate what kind of abortion care this country requires. We need to ask ourselves: what is it about our experiences that we need to keep, and what do we need to change? We can only do that when we are open and vocal about our experiences, both positive and negative. In this way, we can expand our vision of what comprehensive, feminist, on-demand abortion care can and should look like in this country, and we can also work towards building a stronger, more inclusive, and more authentic conversation about reproductive justice in Canada.”

Obvious Child is in theatres now. One Kind Word was just launched in Toronto and will be launched in Halifax next week, with launch dates in Ottawa and Vancouver to be determined. You can get a copy from Another Story Bookshop in Toronto, or online from Three O’Clock Press or Amazon.