Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

The Trudeau government has introduced legislation to set up a parliamentary committee, with members from both the House and the Senate, to oversee the activities of the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and the many other federal departments and agencies that deal with security and intelligence.

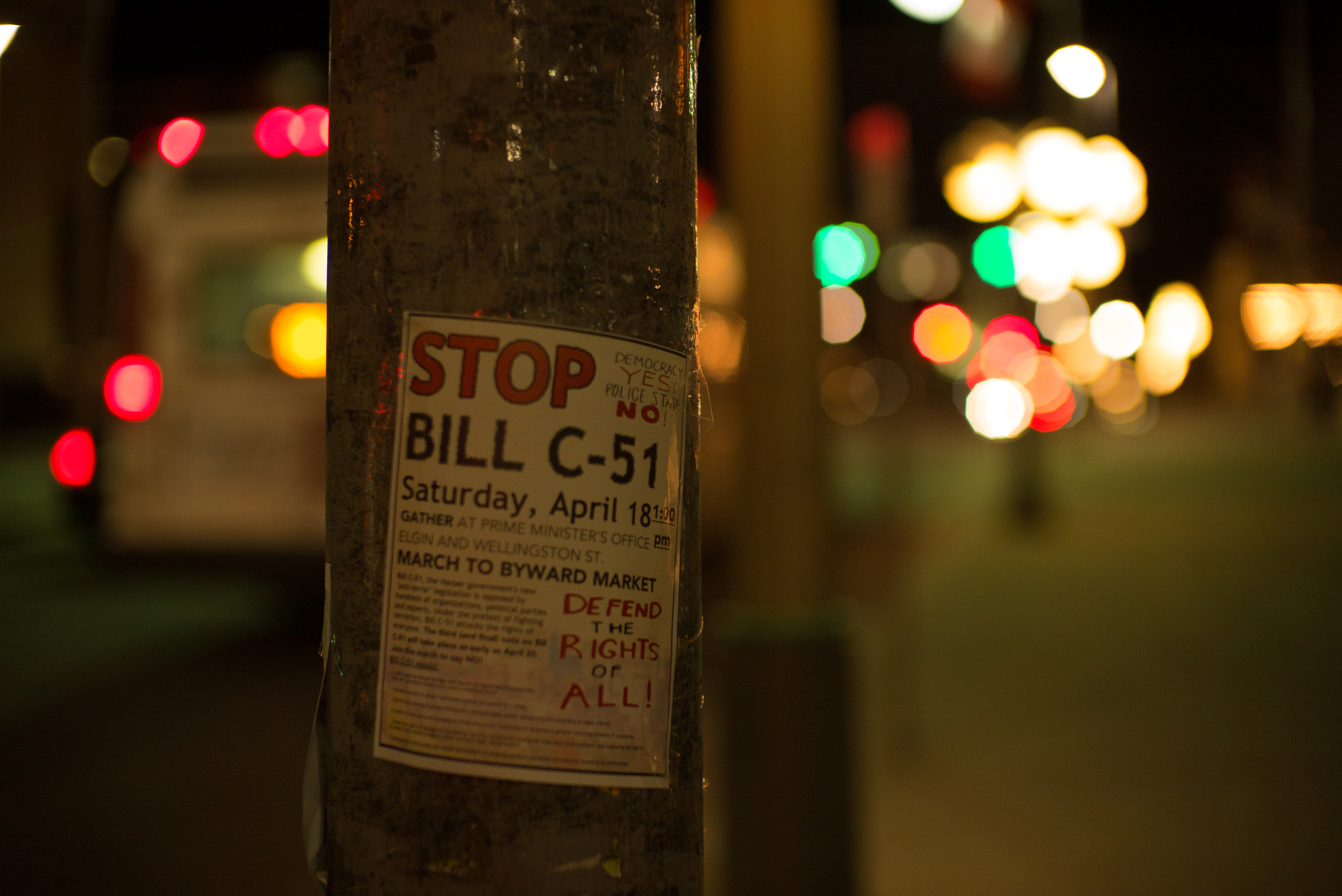

The Liberal government touts this new committee as partial fulfillment of its promise to modify the Harper government’s anti-terror legislation (Bill C-51, now the law of the land) — legislation for which the Liberals voted in favour.

The committee’s members, and its Chair, will be selected by the Cabinet, not by all Members of Parliament collectively. One of Prime Minister Trudeau’s key democratic reform promises during the last election campaign was that all House committee chairs would be elected by all MPs, by secret ballot. That promise will not apply to this new oversight committee, it seems.

Only the beginning of a series of changes to the anti-terror legislation?

“This [committee] will … fulfill a very important campaign promise,” says Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale, “The purpose is twofold, to make sure our security and intelligence agencies are being effective in keeping Canadians safe and simultaneously in lockstep with that to make sure they are safeguarding the values of Canadians, the rights and freedoms of Canadians and the open, democratic character of our country.”

Given what some commentators have deemed is the new security-focused temper of our times, one might assume the government would be content to launch the promised oversight committee, which is to be chaired by veteran Ottawa MP David McGuinty, and leave it at that.

Goodale promises, however, that the government is not through with the package of anti-terror laws that was passed on Stephen Harper’s watch, a package the Liberals consider to be flawed in many fundamental respects.

The minister has launched national consultations that could lead to more, and more far-reaching, changes to the anti-terror legislation.

This consultative exercise, the minster says, “will probably be the most extensive the government of the country has ever seen. We will start with the specific items that were in our platform about corrections that needed to be made in relation to C51, the things that C51 got so terribly wrong, definition of terrorist propaganda for example, making sure the Charter is paramount, correcting some things on the appeal process with respect to the no fly list. That’s the beginning position. That will be forthcoming in legislation later ….”

Lest some of us forget all that is problematic about the anti-terror legislation the Harper government foisted on Canadians about a year ago, here is a refresher.

CSIS with new intrusive powers might more than “Jihadists” in its sights

When we talk of terrorists we often think we are talking only about “violent Jihadists.” The anti-terror legislation makes no reference, however, to such putative enemies of Canada. It merely talks in entirely undefined ways about “terrorism.”

In the federal government’s 2014 Public Report on the Terrorist Threat to Canada, there is a long list of “terrorist entities listed by Canada,” which does, indeed, include many that are notionally Islamist.

But there are many others, as well.

Among those others are: the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam in Sri Lanka, the World Tamil Movement in North America, the Kurdistan Workers Party in Turkey, the Basque Euskadi Ta Askatasuna in Spain and France, and the International Sikh Youth Federation in India and elsewhere.

Think of the implications of listing the two Tamil organizations, to cite just that example

Could CSIS’s new powers encourage its agents to spy on, sabotage and disrupt Canadians who might seek to peacefully protest Sri Lankan government human rights abuses?

It might be natural for CSIS to see such peaceful protesters as fellow travellers of the listed terrorist entities, and thus legitimate targets. There are over 200,000 Canadians of Sri Lankan Tamil origin, many of whom have an intense interest in what happens in their homeland.

Further, the new CSIS powers will not limit the focus of the spy agency to foreign-based, notionally terrorist entities. In September 2014, a Carleton University instructor obtained a report produced by the RCMP’s “infrastructure intelligence team” which identified Canadian environmentalists as a potential threat. The report did not only talk about radical extremists on the fringe, who might resort to illegal actions. It focused on anyone who might somehow “interfere with” the ambitions of industry, especially the oil and gas industry, to carry on and expand operations, however harmful to the environment those operations might be.

Here are the report’s own words:

“It is highly probable that environmentalists will continue to mount direct actions targeting Canada’s energy sector, specifically the petroleum sub-sector and the fossil and nuclear fuelled electricity generating facilities, with the objectives of: influencing government energy policy, interfering within the energy regulatory process and forcing the energy industry to cease its operations that harm the environment.”

Note that all of the activities that the RCMP here states “threaten Canadian security” would fall into the category of the legal, peaceful and democratic exercise of free speech and right to protest.

The legislation gives CSIS the power to engage in dirty tricks

In the 1970s, the RCMP’s security service, which CSIS replaced more than 30 years ago, carried out a series of illegal sabotage and disruption operations in order to counter what it took to be the threat of “terrorist” Quebec separatists.

Security service agents broke into the offices of the left-of-centre Agence de Presse Libre du Québec, acquired dynamite and tried to make it look like it belonged to the Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ), entered homes without warrants hundreds of times, and stole the membership list of a legal political party (the Parti Québecois).

The anti-terrorist legislation gives the security service’s successor organization, CSIS, broad powers to commit the kind of sabotage and disruption operations the RCMP security used to undertake.

Do not be deceived by the bland language of the legislation, to wit: If there are reasonable grounds to believe that a particular activity constitutes a threat to the security of Canada, CSIS may take measures, within or outside of Canada, to reduce the threat.

“May take [mostly unspecified] measures,” says the Bill, but there are precious few limits on those “measures.”

And the legislation specifically mentions a few of the things CSIS can do. For instance, CSIS agents may “enter any place or open or obtain access to any thing; search for… take extracts from and make copies of… information, record[s], document[s] or thing[s]; [and] install, maintain or remove any thing.”

The law only says that CSIS must have “reasonable grounds to believe” there is an undefined “threat to the security of Canada.” That could cover a lot of possibilities.

Many in the RCMP already appear to believe the mere act of questioning the role of the fossil fuel or nuclear industries constitutes a threat to Canadian security.

The legislation makes it a crime to express some vaguely defined views

The anti-terror legislation introduces the new and largely undefined crime of “communicating statements” that knowingly advocate or promote “the commission of terrorist offences in general.”

A person who commits this crime could be sentenced to up to five years in prison.

The “communication” the legislation makes illegal could be done through printed or broadcast material, or online.

The actual words of the legislation are: “Terrorist material or data that makes terrorist material available [emphasis added].”

“Data” that makes terrorist material “available.”

Those words open the door to massive snooping on social media posts, emails, blogs and other forms of online communication. And that snooping would happen not for the purpose of identifying actual terrorist acts-in-the-making. Its purpose would be to root out the mere expression of ideas that the authorities somehow decide amounts to “promoting the commission of terrorist offences.”

Take the case of environmental activists who vigorously argue that the exploitation of tar sands bitumen is, in a variety of ways, a blight on the environment. Could the police deem that by implicitly encouraging others to, in some way or other, sabotage tar sands operations, those activists might be “promoting terrorist acts?”

It is too early to say, but recent and not-so-recent history should make us worry.

Some authorities have tended to frame activism on the environment, First Nations rights, refugees and the poor as all being somehow suspect, at best, and often as inimical to the interests of the Canadian State.

Privacy Commissioner asked for changes, which the Conservatives ignored

During the House committee hearings on C-51 Canada’s Privacy Commissioner, Daniel Therrien, issued a devastating critique of the legislation.

At the time the Conservatives unveiled Bill C-51, cabinet ministers told Parliament that the government had “consulted” the Privacy Commissioner.

They did not say what the Commissioner’s view of the legislation was, but gave the impression he was onside. That was not quite the case.

“The scale of information sharing being proposed is unprecedented,” Therrien said, “the scope of the new powers conferred by the Act is excessive, particularly as these powers affect ordinary Canadians, and the safeguards protecting against unreasonable loss of privacy are seriously deficient.”

Therrien did not mince his words.

“While the potential to know virtually everything about everyone may well identify some new threats, the loss of privacy is clearly excessive,” he warned the government.

And then, to make sure nobody missed his point, Therrien added: “All Canadians would be caught in this web.”

Oddly, while in opposition, Liberal leader Justin Trudeau said one of the reasons for his party’s voting in favour of C-51 was its set of provisions for sharing information on Canadians throughout the government, provisions which Therrien so vehemently deplored.

Those information-sharing provisions can be found in Part One of the legislation and are grouped into a distinct piece of sub-legislation called the Security of Canada Information Sharing Act (SCISA).

SCISA makes it obligatory for all federal departments and agencies to share with CSIS, the RCMP, and all other federal entities that deal with security and intelligence, the reams of hitherto confidential information they possess on nearly all Canadians.

Swept up in this provision are: your tax information, your travel data, data on your importations of goods, and virtually any other data any department of government might have about you.

As Therrien put it, the SCISA “would authorize virtually systematic sharing of information, for broad purposes not all clearly related to national security…”

The Commissioner pointed out that, in addition to the investigation and disruption of “known threats,” information will be shared for the purpose of identifying and preventing activities that are “not yet identified.”

Therrien underlined how any Canadian could be the subject of these new information-sharing provisions.

“We accept that the detection and prevention of national security threats are legitimate state objectives,” he said, but then added that “information-sharing would not be limited to known terrorism suspects; it would include information on everyone, including law-abiding Canadians.”

When the time comes to contemplate further changes to the anti-terror legislation, the Liberals might want to carefully reconsider their support of the information-sharing provisions they once believed to be salutary.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.