Karl Nerenberg is your reporter on the Hill. Please consider supporting his work with a monthly donation Support Karl on Patreon today for as little as $1 per month!

When a major party candidate for the U.S. presidency says he will not necessarily respect the result of the election there is a great hue and cry throughout the land, and quite legitimately so.

And what happens when a Canadian Prime Minister strongly hints he might walk away from one his most emphatic and unequivocal election promises?

Well, there has been some clicking of tongues, and a few expressions of somewhat-more-than-mild disappointment.

But should there not be a greater degree of concern, if not something approaching outrage?

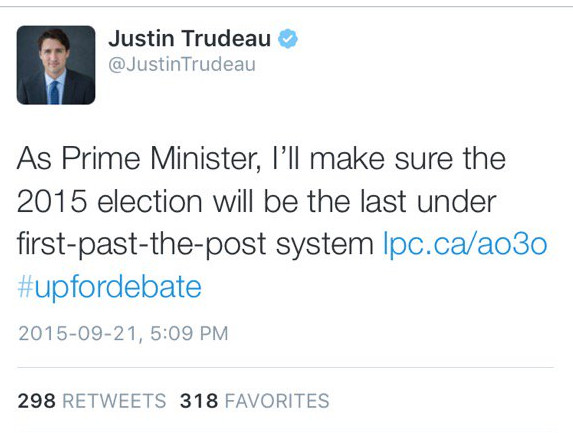

For Liberal leader Justin Trudeau, the promise that the 2015 election would be the last one conducted under the current first-past-the-post system was not merely one among many casually offered campaign pledges.

It was one of his principal means of re-asserting himself and his party when they had slipped to third place in the opinion polls.

Electoral reform was part of a ‘fair and open government’ package

This reporter was a few metres from the Liberal leader when he made the electoral reform pledge, last May, in almost strident and ringing tones.

Trudeau was not committing to study, consider, or consult about electoral reform. He was absolutely promising that, if elected, he would do it, and do it without delay.

Electoral reform was the centrepiece of the Liberals’ “Fair and Open Government” package of democratic reforms.

Trudeau unveiled that package not on Parliament Hill, but a block away, at a highly partisan, campaign-style event in the Chateau Laurier.

At that event, the Liberal leader placed himself in the middle of the room, which was arranged bear-pit style.

In the inner circle were journalists, most of whom had to stand. There was no moderator. Journalists had to shout their questions, scrum style.

In the outer circle were cheering Liberal partisans, bussed in for the occasion.

This was quite consciously designed to be the beginning of the Liberals’ comeback. Having led public opinion surveys for more than a year, Trudeau and his party found themselves quite suddenly in third place, behind both the Conservatives and the NDP.

The Rachel Notley win in Alberta had given Tom Mulcair’s party at least a feeling of momentum. And the Liberals’ both-sides-of-the-fence position on the anti-terror bill, C-51, seemed to have turned off a lot of their erstwhile supporters.

Showcasing democratic reform was supposed to play to Justin Trudeau’s strength as a voice for fresh, innovative and new ideas. It was designed to provide a contrast with an official opposition NDP that Liberal strategists calculated (correctly, it turned out) might have grown too cautious and risk averse.

In case anyone might miss the point, the Liberals plastered their fair and open government document with one key slogan: “Real Change”.

A cornucopia of promises

Aside from reforming the voting system, some of the other promises Trudeau made that day in May were:

- To strengthen parliamentary committees by not allowing parliamentary secretaries (ministers’ understudies) to be members of them;

- To have more free votes in parliament;

- To institute a new, non-partisan system for selecting senators;

- To assure the independence of the Parliamentary Budget Officer, and other watchdogs, such as the Information and Privacy Commissioners;

- To end the abuse of massive omnibus bills;

- To appoint a commissioner to provide oversight on government advertising;

- To limit political party election spending between election campaign periods;

- To create an independent body to organize election period leaders’ debates;

- To restore the long-form census, to respect science, and to instill a culture of data-driven decision making in government;

- To overhaul Canada Revenue Agency practices so that they are more taxpayer friendly;

- To have an equal number of men and women in the cabinet; and

- To restore home delivery of mail.

There is much more. You can read it all here.

Readers will note, at a glance, that the Trudeau government has fully fulfilled some of these promises.

It is 2016 and there is gender parity in the cabinet.

The Prime Minister has also put in place his new senatorial appointment system. The result has been a number of solid appointments of the sort Stephen Harper rarely made, such as that of Justice Murray Sinclair and former Ontario NDP cabinet minister Frances Lankin.

We have had free votes in the House this past year, notably on assisted dying, but it is difficult to say, at this point, whether or not we are seeing more than in the past.

The long-form census has been restored, although we’re not too sure what will happen with home delivery of mail.

New leadership at the National Research Council gives a strong indication of greater respect for non-partisan, open-ended and disinterested scientific research. And public servants report a heady new feeling from a government that is actually interested in their data and evidence-based advice.

When it comes to parliamentary committees, on the other hand, the jury is still out.

There is some disturbing evidence that in its management of committees the Trudeau Liberals have slipped into some of the bad habits of their predecessors.

On Thursday, the Conservative critic for Defence, James Bezan, issued a news release in which he complained about the way the House of Commons Standing Committee on National Defence has been functioning:

“Over the past several months,” Bezan wrote, “The chair has failed to respect individual committee members, parliamentary secretaries have interfered with committee business and the chair has not upheld his neutrality. I believe these actions are disrespectful and are impacting the committee’s productivity….The Liberal government previously indicated that committees would function independently from ministers and their parliamentary secretaries. Unfortunately, the parliamentary secretaries for National Defence…and [for] Public Services and Procurement continue to actively participate in committee business.”

While it may be a bit rich coming from a veteran of a government that was notoriously disrespectful of parliament and the role of MPs, if there is truth to Bezan’s complaints it is a discomfiting sign.

Slipping into arrogance can corrode the public’s good will

There is an enormous tendency for any majority government to slip into habits of arrogance; to act as though it does not have a temporary and contingent mandate from the people, but what ancient Chinese emperors called the mandate of heaven.

To give the Liberals the benefit of the doubt, reforming House committees may be, of necessity, something of a work in process. The aggrieved testimony of one disgruntled opposition MP does not necessarily mean the government has completely abandoned its reform pledges on that score.

But as for the electoral reform promise — well, that was the big one. It occupied centre stage last spring. The Liberal leader, now Prime Minister, took clear and very personal ownership of that pledge.

That leader should be very wary of cavalierly abandoning that key promise, now that he has his majority.

He and many in his party might be tempted to reason that the Canadian people are not particularly seized with the arcane issue of how we elect our parliament right now.

The government faces bigger and more pressing challenges, they could tell themselves, notably on the economy and such major policy fronts as immigration.

That could be a fatal error.

Whatever the level of voters’ knowledge of the details of an election promise, they tend to look askance at politicians who make firm commitments only to so easily abandon them.

The Trudeau Liberals are high in public esteem now, a year into their mandate. If, however, they start to gain a reputation for being disingenuous about their commitments, that could have a corrosive effect on that public esteem.

Karl Nerenberg is your reporter on the Hill. Please consider supporting his work with a monthly donation Support Karl on Patreon today for as little as $1 per month!