Please support our coverage of democratic movements and become a supporter of rabble.ca.

In the final stretch of the campaign trail, Justin Trudeau — Canada’s next prime minister and leader of a majority government — vowed to end boil-water advisories on First Nations reserves within the next five years. A worthy goal, to be sure. But why stop there? In keeping with the spirit of hope and “real change” the soon-to-be prime minister evoked during his campaign, the incoming government should aim even higher and guarantee that every person in Canada has a right to a healthy environment, including the human right to water and sanitation.

Because here’s the truth about water protection in Canada: Although it is home to 20 per cent of the earth’s freshwater resources, Canada has consistently failed to introduce the necessary laws and policies required to ensure that every person in Canada can access safe, clean drinking water. Generally speaking, water availability is not the issue; political will is.

A legacy of underachievement

Government after government has passed the buck on drinking water protection. Today, that means Canada lacks a national water law and rigorous, enforceable water quality standards. Instead, it relies on an uneven patchwork of provincial water policies to protect drinking water. As a result, from coast to coast to coast, our drinking water is not equally protected. And while most major Canadian cities have relatively sophisticated water treatment facilities, many rural, low-income or First Nations communities lack such infrastructure and rely on untreated or minimally-treated water.

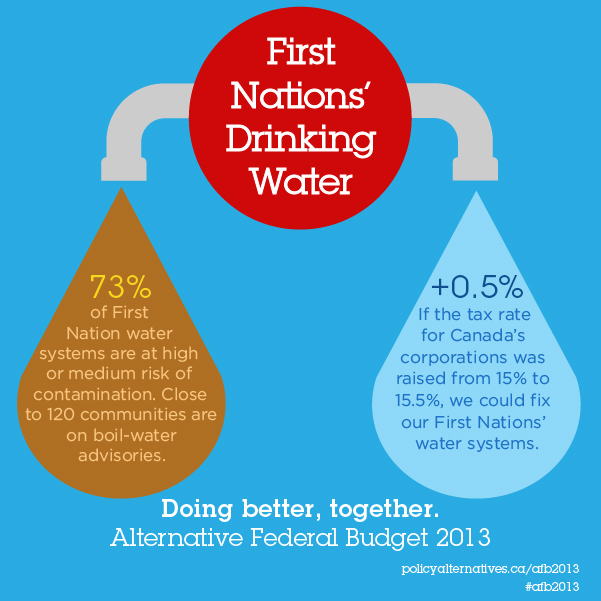

In the absence of national water standards backed by a national water law, a national water policy, adequate funding, and the political will to prioritize these issues, communities under federal jurisdiction, such as First Nations, have little means to secure access to clean drinking water. The Safe Drinking Water for First Nations Act sets high standards but without the adequate funding, leaves communities without the necessary tools to meet those standards. Despite repeated pledges from the federal government to ensure clean drinking water, there are routinely more than 100 water advisories in effect in First Nation communities, with some living under advisories for up to 20 years.

Based on Health Canada and the First Nations Health Authority’s latest figures, there are a total of 162 drinking water advisories in 118 First Nation communities. According to a 2009 study by the UN, First Nations homes are 90 times more likely to be without safe drinking water than other Canadian homes.

Unequal water access amounts to discrimination

Low-income, rural, or Indigenous communities are more likely to have unreliable access to safe, clean drinking water. This isn’t simply an inconvenience, it is discriminatory. The problem is one of chronic, systemic inequity that poses an unacceptable threat to human health and quality of life. Studies show that communities that lack access to safe, clean drinking water face significant health risks, including elevated rates of waterborne illnesses, pneumonia, influenza, whooping cough, and other infections.

Consider that:

- The Neskantaga First Nation has been under a 20-year boil-water advisory, the longest running drinking water advisory in Canada.

- In January 2015, Winnipeg was put under its first city-wide boil-water advisory, but for Shoal Lake 40, it was just business as usual. Although Shoal Lake is within the First Nations’ traditional territory, it has been cut off from the mainland by a channel built to protect Winnipeg’s drinking water source and has been under a boil-water advisory for more than 17 years.

- Residents of rural communities, such as Harrietsfield, N.S., continue to face threats to their drinking water. Groundwater contamination caused by factors including years of nearby industrial activity left Melissa King afraid to bathe her two-year old son at home. Earlier this year, she and her family made the difficult decision to declare bankruptcy and leave her home.

Water is life and a vital part of our day-to-day lives — we need it for drinking, sanitation and domestic uses. All communities need water for livelihoods and for social, economic, cultural and spiritual purposes. Even the federal government admits that every Canadian — no matter where they live or who they are — should have access to safe, clean drinking water.

In 2012, the Canadian government finally recognized the human right to water and sanitation; the problem is that it has yet to implement this right and honour that commitment. Meanwhile, its ongoing failure to introduce a national water law, fund improvements to water infrastructure in First Nations communities, or recognize environmental human rights continues to perpetuate injustices that disproportionately affect the most vulnerable communities in Canada.

A healthy environment and clean water go hand-in-hand

In addition to the lack of clean, safe drinking water, far too many communities in Canada also face threats to their right to live in a healthy environment. Without strong, enforceable laws and regulations, extreme energy projects like oil and gas pipelines, fracking, and tar sands development can put clean air, water and land — not to mention human health — at risk. Many of these projects happen on Indigenous territory without the free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous peoples.

Thousands are also exposed to harmful levels of air pollution every day. Dozens of toxic chemicals already banned in other countries can still be legally used within our borders. These injustices make a clear case that Canada needs to take bold action and recognize our human right to a healthy environment, including a right to water and sanitation.

A roadmap for improvement

The good news is that the incoming federal government has a golden opportunity to dramatically increase access to safe, clean drinking water and strengthen the recognition of environment rights in Canada, beginning with addressing the chronic water crises in Indigenous communities.

That’s why we, along with over 90 First Nations communities and allied organizations, sent an open letter to federal party leaders last week, calling on them to do three things:

- Invest $470 million annually for the next 10 years in First Nations water treatment and wastewater systems as called for by the government’s own National Assessment of First Nations Water and Wastewater Systems, Assembly of First Nations and the Alternative Federal Budget.

- Implement the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and in particular to recognize that free, prior and informed consent of Indigenous peoples is a prerequisite for any decisions or actions contemplated by Canada, provinces or territories that may affect their water rights.

- Realize the UN Human Rights Council resolution on the human right to safe drinking water and sanitation by developing comprehensive plans and strategies, assessing the implementation of the plans of action, ensuring affordable, sustainable services for everyone and creating accountability mechanisms and legal remedies.

Our new government has the chance to start its four-year term on a high note by being the government that takes long-overdue action to end the drinking water crisis in First Nations communities and guarantee every person’s right to a healthy environment, including the human right to water and sanitation. Let’s not let that opportunity pass us by.

Kaitlyn Mitchell is the national program director of Ecojustice, Canada’s only environmental law charity. Emma Lui is the national water campaigner for Council of Canadians, Canada’s leading social action organization.

Photo: World Bank Photo Collection/Flickr

Please support our coverage of democratic movements and become a supporter of rabble.ca.