Capitalism has entered an ugly new era, one that may work well for the shareholders of the world, but not for the rest of us.

I couldn’t help but notice that, on the very same day Caterpillar shuttered the doors of its London, Ontario locomotive plant and headed to low-wage Indiana, the Wall Street Journal reported federal corporate tax receipts as a share of profits had dropped to their lowest level in at least 40 years in the U.S. Sadly, that’s not just an American story.

Lower taxes and lower wages: it’s a one-two punch that has been hard to duck in the post-crisis period, and not because business is on the ropes. Like Caterpillar, the American business sector as a whole has been booking record-breaking profits.

Stubbornly high unemployment, talk of austerity and huge household debt levels have got people worried, on both sides of the border, and some employers are using that fear to their advantage. Newly aggressive demands that workers give up income join the decades-old demands that governments give up revenue. The implicit deal is lower taxes create more investment and competitive cost structures create more demand. Both supposedly create more (good-paying) jobs. Lower taxes, check. Lower payroll costs, check. More good-paying jobs here at home: Insert sound of crickets chirping.

According to the Congressional Budget Office, the effective tax rate on the business sector in the U.S. — federal corporate tax receipts as a share of domestic profits — had fallen to 12.1 per cent by fiscal 2010-11. It had averaged 25.6 per cent between 1987 and 2008.

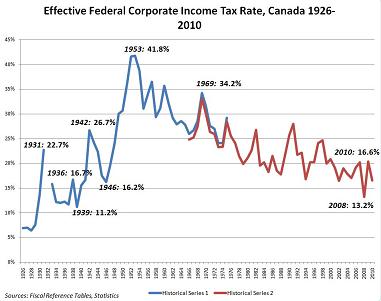

In Canada, too, federal taxes on profit have been falling for decades, dropping to 16.6 per cent by fiscal 2010-11 after briefly dipping to 13.2 per cent in 2008, a level not seen since the Great Depression. The long-term trajectory is headed towards effective corporate taxation rates of the Dirty Thirties as federal rates continue their steady downward march, through recession and recovery.

Source: Fiscal Reference Tables and Statistics Canada

Unlike the 1930s, corporate profits in Canada have rebounded since the 2008-9 crisis, nearing the previous high water mark ($204 billion in the third quarter of 2011 — hit by roller-coaster stock markets — up from $135.8 billion in the second quarter of 2009 but shy of the peak, $247 billion in 2008’s third quarter).

Back in the 1960s, a successful corporation could expect to turn over at least 25 cents on every dollar made to the federal government, to help build Canada. It didn’t seem to stop them from building business and profits too. In fact, the economy was on a growth spurt.

Despite growth today, there is no shortage of profitable firms telling workers they can keep their jobs only if they agree to get less. Yes, today growth is slower, and yes, more companies now compete on a global stage. But slow growth is exacerbated by a view — dominated by business interests, and shared by many bureaucrats and politicians — that lower taxes and lower wages are the best way forward. Call it sociopathic economics.

Boiled down, the Caterpillar story was about a company making a union an offer it had to refuse: cut wages in half, eliminate cost of living increases, eliminate defined benefit pensions and increase co-pays on benefits. It was all end game, no discussion. Production headed for Muncie, Indiana, where wages are $12.50 to $14.50 an hour, less than half the $35 skilled welders in Canada were making until December. The local daily in Muncie notes how tough it is to find and retain skilled workers at that pay, and the struggle faced by local businesses whose clientele is losing economic ground.

The Cat fight released fresh blood in the water for the sharks. But it’s just the latest, most egregious example in a string of stories that have emerged in the aftermath of the global economic meltdown.

In Quebec, Rio Tinto wants to increase the number of contractors in the workforce, from 10.7 per cent now to 27 per cent. They are paid at half the wages of unionized workforce. Company earnings over the last year, at $15.5 billion, beat records and market expectations.

In B.C., workers at Extra Foods are resisting Loblaw’s attempt to cut wages in half.

Loblaws, with almost $40 billion in annual business, announced a 19.8 per cent increase in quarterly profits in November.

In Fort Frances Ontario, workers with Resolute Forest Products (a.k.a. Abitibi Bowater) took a $10/hour pay cut, lost vacation pay, and now pay $180 a month for short-term disability pensions, totalling an 18 per cent pay cut last year. The company is not hurting. It’s buying another firm for $71.5 million.

Global mining giant Vale saw its revenues double to $46.5 billion in 2010 from the previous year while withstanding a 14-month strike in Ontario and an 18-month strike in Voisey’s Bay, Labrador. Vale sought, and got, concessions that brought Canadian operations more in line with the rest of its production network, which is mostly in developing nations.

From casino workers in Atlantic City, to electricians in England and meatpackers in New Zealand, hugely profitable firms are telling workers they can’t keep what they’ve got.

These stories display, at their core, a shockingly naked desire to reduce the incomes and bargaining power of workers. It’s not because there is no money.

To these blatant ways of redistributing income, from poor to rich, add other, more subtle strategies.

Domestic and foreign firms are “insourcing” low-wage workers, through temporary foreign work permits for low- and higher-skilled jobs. Others are creating two- and three-tier workforces, the better to reduce payroll costs and divide workers’ interests. It’s putting downward pressure on the wages and incomes of the associated supply chains and local economies.

The costs of production in some job-starved U.S. markets are closing in on the costs of producing in emerging markets, once transportation and productivity concerns are factored in. Low-wage havens can be found, and created, at home.

These trends are not just happening in the U.S.

Ontario’s Society of Energy Professionals stood their ground against Hydro One for a 105-day strike in 2005 to prevent two-tiering of the workforce, hoping to protect the next generation of hires, mostly young women and racial minorities. They won then, but two-tiering has become staple fare at the collective bargaining table in the last couple of years, a routine demand of employers in both the public and private sectors.

The use of temporary foreign workers has also exploded since the recession began, strictly a matter of federal public policy. Different compensation for people doing the same job is increasing in unionized settings and non-unionized settings alike, partly due to the accelerating use of contractors and temporary workers. The result: Newcomers and youth are pitted against workers with more seniority and job permanence, and everyone’s attention is distracted from the employer’s ability to pay.

The wage floor is sagging, pulling the prospects for everyone but the elite downwards. A recent study by the Metcalf Foundation showed that the proportion of working poor in Toronto soared by 42 per cent from 2000 to 2005, while the economy was still growing. Of the working poor, 73 per cent were not born in Canada.

Where is the middle class supposed to come from for our children and the immigrants, the people on whom we will rely and who will create the new Canada?

True, this is not the first time employers have told workers to suck it up. After the free-trade deals of the 1980s and 1990s, companies simply moved operations to lower-wage climes, shedding hundreds of thousands of good-paying Canadian jobs in the process. Back in the 1930s, when such options were not so readily available, bosses fought unions mightily, but to stave off paying more, not ram through cuts.

You have to go all the way back to the robber barons of the 1880s and 1890s to see growing, successful companies — like the railroads and coal mines — boost profits further by extracting wage concessions from existing workers.

Today, a growing number of employers in advanced economies are demanding terms of employment that roll the clock back decades. Keeping your job means accepting wages and working conditions that narrow the margin between workers here and in emerging markets.

If memory serves, globalization was sold as an opportunity to export the First World economy and conditions, not import a Third World standard for workers.

Some, not all, corporations view both governments and unions as pesky impediments to making money. These corporations don’t talk. Or give. But they’ll take. And there is no end to what they’ll take. It’s a real concern if their numbers keep growing.

Democracies and collective bargaining provide ways to air multiple views and find a working balance between interests. Without processes of talking, giving and taking, the bullies prevail. Of late, there has been a rise in the number of bullies, and a celebration of corporate strength … as if that is all that matters to an economy or a society.

The snatch-and-grab ethos that has emerged in the wake of the global economic crisis may fatten an individual corporation’s bottom line; but if too many companies play this game, everyone but the giants lose.

As these big corporate players drive down their costs and rack up ever-higher profits, they build up their war chests to buy up the competition. That turns workers, suppliers and governments alike into price-takers, and has us all scrambling to attract capital and jobs with, you guessed it, lower taxes and lower wages.

It’s like a bad joke: the more successful the business sector is at driving down its costs, the harder it gets for families and communities to go about their business.

The chart above shows the scorecard of success on the tax front. Rapidly escalating income inequality will track the legacy of the new war on labour, making past trends look like a walk in the park.

This is not the type of capitalism anybody should be rooting for, in the search for enduring recovery, growth and prosperity.

This article was first posted on Behind the Numbers.