The opening of Brandon Grossutti’s Pidgin restaurant across from Pigeon Park in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside has marked a stark difference in the way the local anti-gentrification movement has been represented and undermined in the media and public discourse. Up to this point, while overtly poor-bashing editorials and policies occasionally surfaced, the characterization of resistance to relentless development in the city has been acknowledgment with sympathy but restrained disagreement — perfectly exemplified by Mayor Gregor Robertson’s hand-wringing concern as he pursues policies of ruthless real estate expansion and the displacement of low-income people.

Not anymore. While Vancouver’s mainstream media outlets would consistently pepper their coverage of the Downtown Eastside with stigmatizing phrases like “Canada’s poorest postal code” or write with the tacit belief that only market solutions can “fix” the “beleaguered,” “notorious,” or “crime-stricken” neighbourhood, local press has given pidgin-holing a whole new meaning.

The Province declared that it was “sickened” by “the sense of entitlement displayed by Vancouver’s taxpayer-funded poverty industry.” In an incredible sleight-of-hand, people who have dedicated their lives to serving a community which all levels of government continually leave to suffer have become an “entitled industry,” while the purveyor of a 5$ plate of pickles, who believes he has the right to open a restaurant wherever he wishes simply because he has the right venture capitalist behind him, deserves to be “citizen of the year.” Astonishing.

CBC’s Stephen Quinn in The Globe chimed in with a slightly more circumspect but still scathing indictment of the activists, calling them “segregationists” who should be happy that “the rich” (with whom he graciously includes himself with a “we”) are trying to “spruce the place up.” As if the only way to improve a neighbourhood is by welcoming yet another insufferable Portlandia caricature into Gastown and environs.

Of course, the real segregationists, as Ivan Drury pointed out on Quinn’s On the Coast, are those who wish to push out low-income residents on the banner of “mixed communities”; while anyone visiting the neighbourhood nowadays can see that the only diversity on display is the cultural distance between a matcha mojito and a cask-conditioned saison. Why are there no mainstream editorial boards speaking out against the ghettoes of well-heeled douchebags?

Quinn mocks the idea that Pigeon Park, aside from the fact that it lies on unceded Coast Salish territory, is “a centre for indigenous culture.” Yet the park, like the northwest corner of Main and Hastings, has long stood as a gathering place for urban Aboriginal people in Vancouver, where simply taking up space in the city, remaining visible, laying claim to a land and a neighbourhood which belongs to them by law, history and right, has become a political statement. Long before Occupy titillated, enamoured, then repulsed the city’s centre-left detachment, Vancouver’s indigenous people have been announcing — silently, inconveniently, unprofitably — that they exist.

The deepest irony here is not Quinn’s perverse understanding of the history of colonialism, displacement and civil rights, but rather how those calling for the protection of our most vulnerable have been vilified and maligned by local media. Buttressing the protest against Pidgin has been Jean Swanson’s recent plea for a “Social Justice Zone”: a humble request for a city-protected and curated civic space where “low income people and their basic human and social needs have priority over profit.” Listening to Vision Vancouver’s municipal strategy, this sounds exactly like what they want: mixed-income communities with a protected allotment of social housing.

Yet this demand is met by the mainstream media and Vision’s city councillor Kerry Jang with scorn: “They’ve made it clear to me they want a 100 per cent low-income neighbourhood that is subsidized forever. But mixed communities work best — mixed buildings, mixed communities, mixed neighbourhoods….There’s no longer this class warfare that’s gone on too long.” What’s staggering about Jang’s claims is not his misrepresentation of Swanson’s proposal, but his identification of “class warfare” as the key threat to the DTES — not how it’s usually understood as the rich’s abuse and exploitation of the poor, but the reverse.

There’s a reason, and all stakeholders in this dispute know it, why the opening of Pidgin has incited both pro- and anti-development sides to circle their wagons. It’s not only the symbolic nature of the restaurant’s name — a move akin to the British Empire moving onto the shores of Lake Ontario and opening up a chip roll shop named “Haudenosaunee” while the Iroquois stand around and watch. And it’s not only the ever-shifting fault line of gentrification — now Cambie street, now Carrall, now Main. It’s that the city’s very soul is at stake.

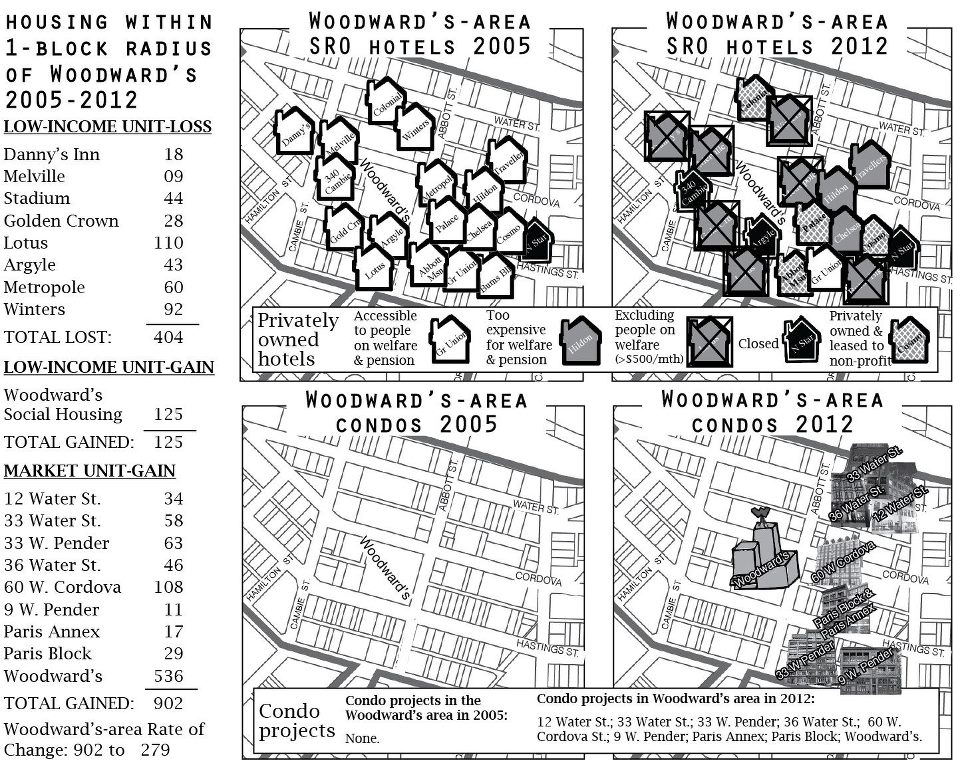

As Wendy Pedersen’s graphic at the top of this post shows, the critical mass of affordable single-room occupancy rental units (SROs) in the Downtown Eastside is dangerously low. Most pundits and policy-makers (except for Jang above) don’t seem to dispute this, the point of contention seems to be whether or not it matters. People like Quinn perhaps prefer seared Romaine leaf and brined tempeh sliders to the community which brought Canada InSite and courageously exposed our collective shame of the missing and murdered women of the Downtown Eastside. Those who stand in solidarity with that community as they struggle in an increasingly unpopular fight, like those who stood tall in the legendary Woodsquat of 2002, see something else: a community based on notions of respect, transparency, reciprocity and social justice.

Every episode of Andy Longhurst’s excellent CiTR podcast on urban issues, The City, opens with a quote from David Harvey’s Rebel Cities: “The question of what kind of city we want,” Harvey argues, “cannot be divorced from the question of what kind of people we want to be.” It’s this fundamental question, which impacts every resident of Vancouver, that is being played out right now in front of Pigeon Park.