Like this article? Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

The death of baby Elijah in North Toronto has gripped the hearts of many this past week. I’m sure my Facebook feed was not unique in being filled by outpourings of grief and support for his family.

Not long after, news broke of another toddler found under-dressed, wandering in the cold in Etobicoke. The child was OK, charges were laid against the mother, and where sympathy and grief followed the story of baby Elijah, grief was replaced by relief and blame.

Another story of two toddler deaths got much less attention. The deaths of Harley and Haley Cheenanow, caused by a house fire on a reserve in Saskatchewan, ignited a debate about the actions (or inactions) taken by fire services.

Rather than their parents, it was the leadership of the community who were blamed by many people. Because, for Indigenous people, the roles of “parent” are assigned to anyone we’re looking to blame.

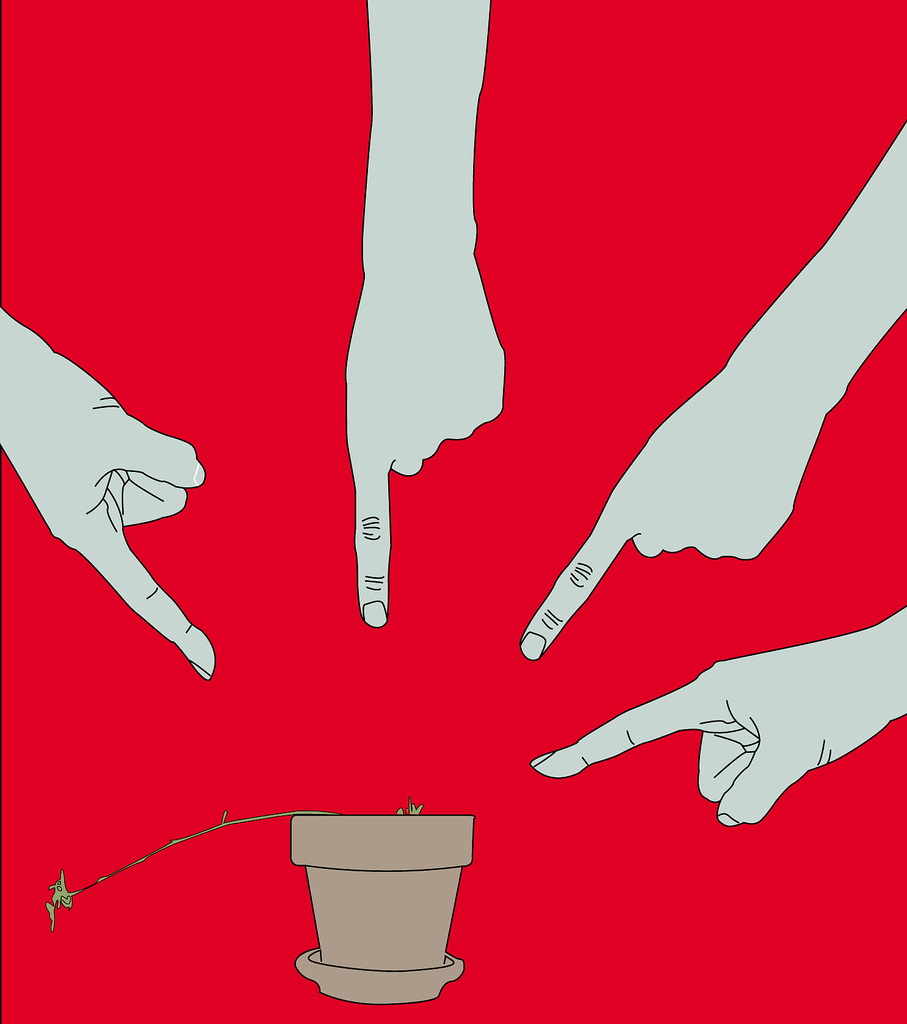

Blame is the projection of grief, sadness or fear. It is the projection of our own inadequacies; of our own feelings of, “oh god, that could be my kid” wrapped up in “thank god I’m a better parent than that.” It pretends that all things are equal, that all family situations are equal and all children are essentially the same.

But it’s malicious. Blame, when targeted towards individuals, shifts the focus to their perceived personal failings. It starts from a place that believes that some parents just don’t love their children as much as others.

When applied to the proper structures, the process of applying blame changes entirely. Why are Indigenous children on reserve ten times more likely to die in a fire? Is it because a single First Nation stopped paying for fire services (because those fire services weren’t being delivered)? Or is it because Canada still refuses to fund First Nations communities properly leaving local leadership to be in a perpetual state of balance, ready to collapse at any moment?

And how could household debt ballooning, good jobs disappearing and social services evaporating not have an effect on the already precarious lives of many parents?

Personal blame is a function of neoliberalism. Neoliberalism tells individuals that there is no such thing as community and that you are wholly responsible for your own decisions. It ignores broader social forces, like what happens when parents can’t make ends meet and are forced to work longer just to get by. It erases the fact that we are not equal and society demands minimal effort from some and maximum effort from others.

It also tells us that there is no one left to help you: not the state, not your neighbours. It places enormous strain on grandparents, aunts and uncles or close friends and other family. It erases the thousands of people who are ready to help regardless of the circumstances.

For baby Elijah, the community broke through this narrative: $170,000 was raised for the family in an outpouring of support and love. For the tragedy at Makwa Sahgaiehcan First Nation, the tragedy has (incredibly, though predictably) generated even more racist hatred and will not likely result in the kind of fundamental changes necessary. A crowdfunding campaign has raised $2200 for the family.

Parenting is hard; not like math or writing kind of hard, but like extended and agonizing war kind of hard. If you can afford the extras: the live-in caregiver, extra curriculars, the toys and clothes, it might be less hard, but it’s still hard. If you’re struggling to survive, live hours away from the closest emergency room, are hungry and have to boil the water that comes from your taps every single time you use it, it’s Herculean hard.

Parenting is hard if your child is hard-wired to be docile, chatty and uninterested in pulling apart the various wires you have the connect your appliances to energy sources.

Parenting is very, very hard if your child is hard-wired to run everywhere, all the time, bang his head on every corner in the house, empty drawers full of knives and then practice falling down the stairs.

Parenting can be impossibly hard if you rely on social programs to help make what is already very hard a little easier, and those social programs slowly disappear.

And if you lay blame at the feet of the parents or the family and ignore these realities, you’re probably an asshole.

Being a parent today is financially harder than any other time since the Great Depression. This means that people who have the financial means to get by will scrape by, while others who don’t, exist on a house of cards, doing whatever they can to stop the cards from collapsing in on themselves.

And when something teeters too far to one side, families can face impossible tragedy.

With a federal government who has no interest in helping the poor or middle classes, and most provincial governments choosing austerity rather than investment, the struggle for parents will only continue to get worse. And buying into the narrative of personal blame simply creates the conditions to justify these policies and make it easier for governments to enact them.

Blame has been used as a tool of oppression for centuries. It continues to be used to shame mothers, shame Indigenous people and shame other oppressed people.

We can’t buy into this. Leave the blaming to the forces that want us divided. In times of crisis and extreme tragedy, meet others with love, compassion and humility and lay blame with the structures that perpetuate inequality.

Image: Flickr/iandesign