Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

As a young teen studying at the Illinois School of Ballet, I didn’t follow sports much, which is probably why I didn’t recognize the big man right away. He was standing on the outside sidewalk of Hyde Park’s new Harper Court shopping mall, looking out, streetward.

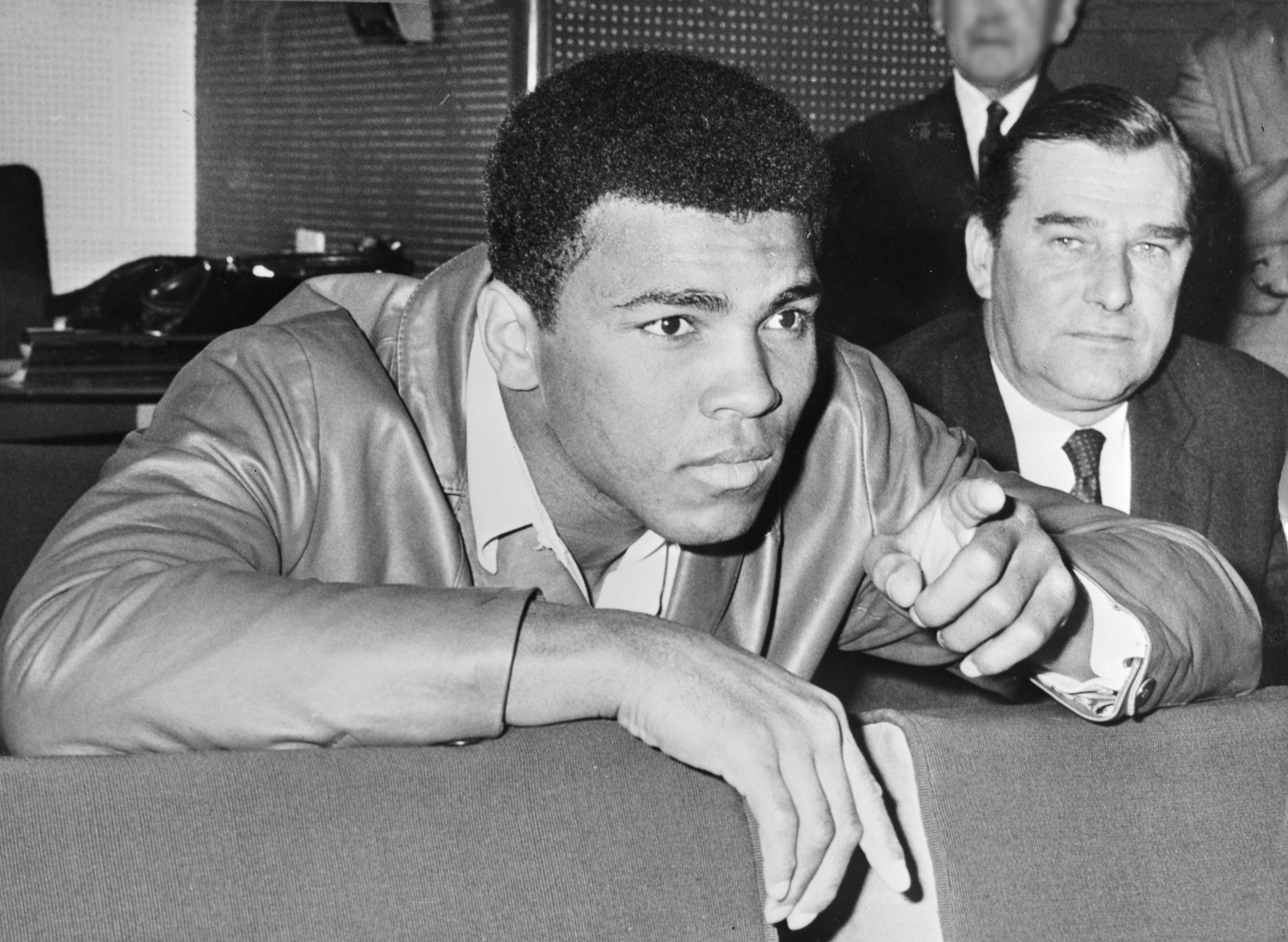

He was well dressed in slacks and a blazer, a light-skinned African American with closely cropped hair. I actually stood next to him for a moment, figuring out where I wanted to go next. The top of my head came to the bent elbow of his folded arms. My dad was 6’2″, but this guy was really big.

A block away, it hit me: I’d just crossed paths with one of Chicago’s most famous residents, champion boxer Muhammad Ali. Everyone knew he lived in Hyde Park, the first racially integrated Chicago neighbourhood. The Hyde Park Herald report said he’d been a guest at the Harper Court opening ceremonies.

Half a dozen years later, I found we were standing on the same sidewalk again, metaphorically speaking, as I quoted Ali’s words in arguing with Scott (my boyfriend at the time) that we should resist too. Scott had dropped out of college and was eligible for the draft. But he trusted to luck to protect him. And when he did get drafted, he took the step forward and entered the army.

Not so Muhammad Ali, the Heavyweight Champion of the World. He was supposed to be the toughest of tough men. He certainly won and kept his title in brutal prizefights. (One of the oldest known sports, boxing was hugely popular in the 1960s, maybe because it showed well on the early TVs.) Cassius Clay converted to Islam in 1964, changed his name to Muhammad Ali, and embraced non-militarism.

“On April 28, 1967, Ali refused to be drafted and requested conscientious-objector status,” the New York Times reported. “He was immediately stripped of his title by boxing commissions around the country. Several months later he was convicted of draft evasion, a verdict he appealed. He did not fight again until he was almost 29, losing three and a half years of his athletic prime.” Eventually, he did win back the Heavyweight title — twice. He also won his right to CO status, at the U.S. Supreme Court.

Time after time Ali faced the cameras with an astute racial and class analysis of the Vietnam war:

“My conscience won’t let me go shoot my brother, or some darker people, or some poor hungry people in the mud for big powerful America. And shoot them for what? They never called me nigger, they never lynched me, they didn’t put no dogs on me, they didn’t rob me of my nationality, rape and kill my mother and father…Shoot them for what?…How can I shoot them poor people? Just take me to jail.”

With broadcaster Howard Cossell’s help, Ali spent the three years he couldn’t do his fighting work, touring universities, talking about boxing and about why he refused to be drafted. He spoke openly about his conversion to Islam, and cited his faith as the reason for his war resistance.

He rebutted critics who compared his job to being in the army. “In boxing the goal is to win the fight,” he said. “In war, the object is to kill, kill, kill, kill, kill innocent people.” Although the army insisted he had only two choices, the army or jail, he said, “There is a third way, and that way is justice.”

He trusted the American legal system, even while he joked about breaking open his piggy bank for gas money to the next university. “I get $1,500 an appearance,” he said. “That’s good money.” Exonerated, he received $4 million for his next championship fight.

“Muhammad Ali bridged a major divide when he refused induction into the armed forces,” writes Richard Eskow of the Campaign for America’s Future. “The civil rights and anti-war movements of the 1960s were often divided by race, kept apart by those who were afraid of losing hard-won gains and by cynics who knew that to divide is to conquer….After he was suspended from boxing, Ali spent three years speaking to college students and other groups of all races about both civil rights and Vietnam. When Dr. King came out against the war despite fierce opposition, he cited him, saying: “Like Muhammad Ali puts it, we are all — lack and brown and poor — victims of the same system of oppression.”

Scott and I had reached the same conclusion — that the oppressive system was universal (worse for some than for others) and for us it was unbeatable, at least at that time. So after two rounds of boot camp, he deserted the army, and invited me to come to Canada with him.

By the time we split up three years later, I’d put down enough roots in Toronto to want to stay. And following Muhammad Ali’s lead, with a lifelong background in civil rights and anti-war work, I continued to promote peace and equality in my own way. I’ve met a lot of other U.S. immigrants with similar stories, especially women.

Of course, no one can compare to Muhammad Ali’s influence then or now. He was a giant figure who strode his own path and spoke his own truth.

“The number one greeting in my religion is ‘Peace,'” he said. That’s something Westerners still don’t understand about Islam. Now we live in a time when women wearing hijabs face attacks because ignorant people perceive them as threats (or easy targets). How ironic to reflect that Muhammad Ali, the man Sports Illustrated acclaimed as “Sportsman [Athlete] of the Twentieth Century,” was pilloried for preaching peace in the name of Allah.

Penney Kome moved to Canada on January 19, 1968, and immigrated a year later. She is writing a book about U.S. women who moved to Canada during the Vietnam War era.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons