President Obama put the idea of raising the minimum wage on the radar in the U.S. It deserves to be on the radar in Canada too. That’s because low-wage work is on the rise.

Obama says raising the federal minimum wage from $7.25 to $9 an hour is good for families dependent on low-wage jobs, and for businesses dependent on more consumer power to fuel their growth. A growing economy helps balance the books too.

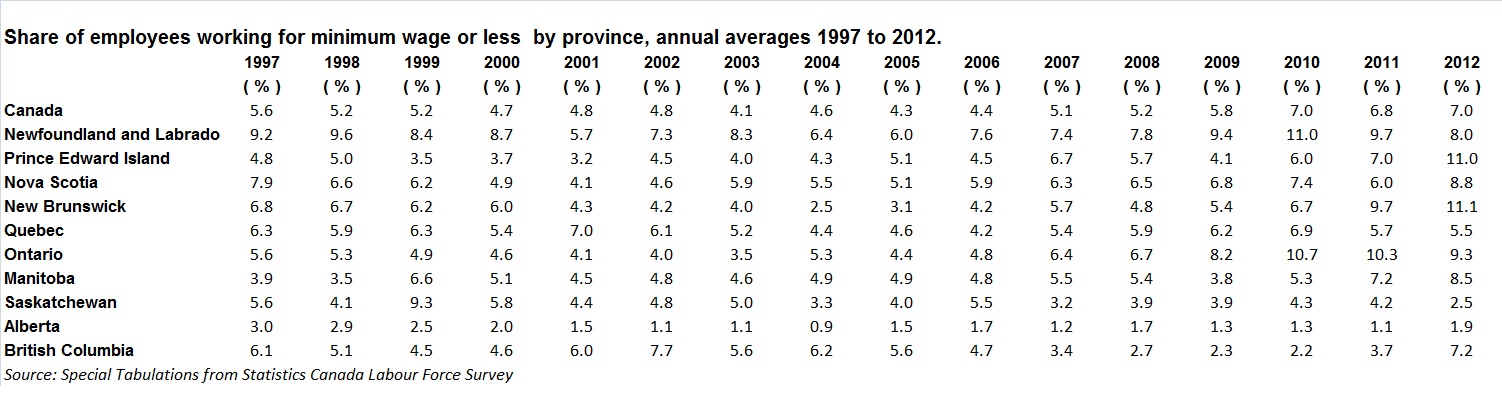

Nowhere is this more important to consider than in Ontario, where minimum-wage workers now account for almost one in 10 employees, more than double the share of a decade ago.

Ontario’s workers are more reliant on minimum-wage jobs than any other part of the country, but for Prince Edward Island and New Brunswick.

Kathleen Wynne, please pay attention.

With more people working at or near the minimum wage in Canada, freezing the statutory minimum means a bigger share of consumers will lose purchasing power to inflation. That’s bad news for the economy, since household spending drives 54 per cent of gross domestic product.

There has been no federal minimum wage in Canada since 1996. Ontario and British Columbia have the highest minimum, at $10.25 an hour. No province today has a minimum wage that matches the peak inflation-adjusted value of $11.50, achieved in the mid 1970s.

Most provinces have increased their minimum wage, right through and since the recession. Ontario’s minimum wage workers haven’t had a raise since March 2010. Inflation has taken a 6.5-per-cent bite of the minimum wage’s purchasing power since then.

Just over 1 million Canadians are paid at the minimum wage. Ontario accounts for over half of them (534,000).

Many people could see a welcome increase in take-home pay if the minimum wage were raised in Ontario to $11.50 an hour, recommended by Ontario’s biggest anti-poverty group, 25in5, and the same as it was in the mid 1970s, if you take inflation into account.

Let me make that real for you. A person working full-time, full-year at a minimum wage job in Ontario makes $20,500 before taxes. With the increase, they could make $2,500 more, pre-tax.

People at the bottom of the income spectrum spend all the money they have, and more. Increase their pay, they spend more money, raise demand, boost the economy. Employers don’t create jobs; consumers do.

But raising the minimum wage could mean job loss too. That’s the main point of those who argue increasing wages will do more harm than good (though why that only applies to workers and not bosses beats me).

There are solid arguments against raising the minimum wage from Stephen Gordon, Morley Gunderson and Gary Becker. But there are plenty of counterfactuals in this debate.

Importantly, some employers can absorb or pass on higher costs more easily than others, whether for labour or other inputs.

It’s often assumed that employers who hire minimum wage workers are small businesses, who would be challenged by even a small increase in labour costs. Surprise: more minimum wage workers are being hired by businesses with more than 500 employees over time. In 1998, big business hired 29.6 per cent of all minimum wage employees in Canada; by 2012 they employed 45.3 per cent. In Ontario, big business accounts for almost half of all minimum-wage workers. Raise the minimum wage by just over a dollar an hour and those Tim Horton’s and Canadian Tire jobs aren’t going to disappear.

But won’t our beleaguered young workers be hardest hit by job losses if you raise the minimum wage? It’s true most minimum wage job-holders are young. Raising the minimum wage would affect them in two ways — increase the pay of those who work a minimum wage job (making it easier to pay for college or university, and not get as deep in debt); and increase unemployment.

Wait. The minimum wage hasn’t increased since 2010 in Ontario and the number of unemployed young workers in Ontario is still rising. Clearly other factors are at play — like an economy that’s not growing very fast.

And, in case you didn’t notice, an increasing share of minimum-wage workers aren’t kids. They’re over 35. Alberta has doubled its share of adult minimum wage workers over the past 15 years, to 33 per cent. One in four minimum wage workers are adults in Newfoundland and New Brunswick. In Ontario, it was 27 per cent, up from 17 per cent in 2004.

Every year the costs of basics like housing, post-secondary education and energy rise. Wages have increased higher up the job ladder. When should the folks on the bottom rung see an increase? Never?

People will say, with the economy so fragile, this is no time to raise the minimum wage. But it has been raised every year in almost every province outside Ontario, and jobs have been increasing.

A clear plan to raise Ontario’s minimum wage from $10.25 to $11.50 — and indexing it to inflation thereafter — could increase household incomes, purchasing power, even business confidence. It can bolster the economy, from the bottom up.

Less inequality, more growth. What’s not to love? We should be raising the roof about the benefits of raising the wage floor.

A version of this article appeared today in the Globe and Mail’s Economy Lab.

This version includes references to the debate plus charts and graphs from data specially tabulated from Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey. The data don’t include the self-employed.