Most of the jobs added to the Canadian labour market in 2014 were part-time — prompting headlines such as “Experts fret Canada becoming a nation of part-time workers.”

Are we really a part-time nation? Well, 80 per cent of workers in Canada are full-time, and a large majority of part-time workers choose to work part-time hours. So, no, we are not at the verge of some part-time workopolypse. But the labour market has been changing, driven partly by demographics (aging) and women entering the labour force.

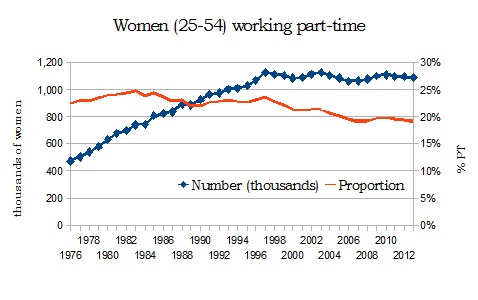

Between 1976 and 2013, the number of core-age women working part-time jobs more than doubled — but the proportion of those women working part-time actually fell.

In the early 1980s about one in four (25 per cent) working women between 25 and 54 held a part-time job. By the mid-2000s that number had dropped to one in five (20 per cent). This means that as women entered the workforce in huge numbers, it became more common for them to hold full-time jobs as well.

A breakdown of part-time workers by age yields some interesting findings as well. When people think of part-time workers, they overwhelmingly picture pimply teenagers. But over time that has been less and less true.

Source: CANSIM 282-0002

In 1976, more than 30 per cent of part-time workers were between 15 and 19 years of age. Now they make up less than 20 per cent of the part time work force.

At the other end of the age spectrum, workers between 50 and 65 used to comprise only 10 per cent of all part-time workers, and now make up more than 20 per cent. As older workers need to stay in the labour force longer in order to supplement failing (or absent) pensions, this trend will likely increase.

All of this sparks a larger question: Why should we care about the number or proportion of part-time workers anyway?

Labour economists dissect the details of the monthly Labour Force Survey with the intensity of wild animals who have landed a fresh kill. We’re hungry for data and answers, and search endlessly for the crosstab that will give us a fresh perspective on what’s happening in people’s lives across the country.

We care about the number of jobs, the quality of jobs, and the wages of jobs, because we care about the well-being of workers and their families. Under our current economic system, jobs are the main way that we distribute wealth — so it matters, a lot.

Very often the Labour Force Survey doesn’t have the answers. But it gives us a place to start asking questions.