Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Jian Ghomeshi goes to trial today. And so, in a way, do Canadian women. This trial is not only about a man who violated the four women pressing charges, but about whether we, as a society, trust women who tell. It’s about the shockingly low rates of sexual assault prosecution and conviction in our country and the shockingly high number of women who have had traumatic sexual experiences. It’s about whether we welcome these women and their stories into our public discourse; about whether we can hear them with respect.

It’s personal for me. Today and every day of the next month, I am sharing my own stories of sexual harassment and violence. I will be honest and forthcoming and it is with some trepidation that I take this plunge. But I can’t not do it. The Ghomeshi scandal has one hell of an undertow.

***

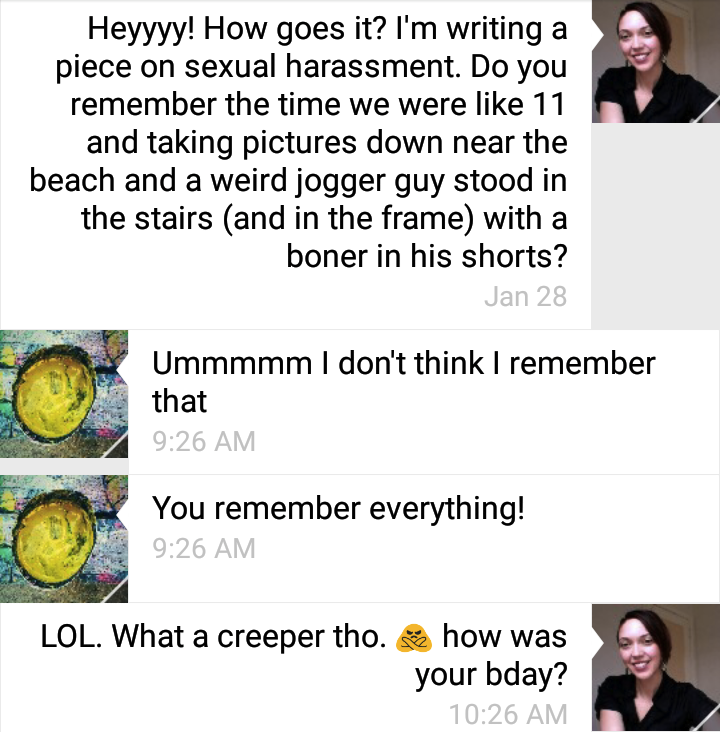

On October 27, 2014, my sister (above, right) called me at my San Francisco job site to tell me that the CBC’s biggest star, talk show host Jian Ghomeshi, had been fired. No allegations had yet been made. Ghomeshi had simply outed himself on Facebook, claiming that he was but a nice boy into kinky sex and Canada just couldn’t handle.

We assumed he had been fired for general douchebaggery. We talked about the PR nightmare, his attempts to get out in front of the story, and how Toronto’s BDSM community must be in a tizzy. After hanging up, I chuckled at the hubris of powerful men. It all felt essentially harmless, more fuel for our mutual obsession with public broadcasting. I had no way of knowing that this event would tear me up inside, that Ghomeshi’s “strange, enticing, weird, normal, or outright offensive” actions would, across the miles, take me to dark places I had once forgotten.

Online, my entire social network rushed to tell the world that they hadn’t liked Ghomeshi anyway. That he was smarmy, sleazy, oversexed; that it really irked them when he kissed Joni Mitchell’s hand. Voices of Canada’s creative class rushed to claim that they “knew.” They knew he was an asshole all along! They knew he was pushy, invasive, dangerous! As if the only thing better than knowing a celebrity was knowing that he was a serial abuser. Few stopped to question the complicity of this knowledge.

I didn’t know. I didn’t know much about Ghomeshi at all. I knew that he was nice to my aunt when he ordered a dozen roses from her shop, and that he had conducted a very serious interview with Brianna Wu about rape and death threats from Gamergate. Despite having worked in the Toronto arts scene, I had never met him. I was pretty sure I knew none of his accusers.

387 times in 11 months

I am mother to two young children and was working hard at an agency providing therapy to homeless families. I live an entire country away. I had no reason to care much.

But as the week wore on, and The Toronto Star published its piece detailing the allegations, I found that I did care. I cared a lot.

I cared so much that I began to Google him daily. Then several times a day. Sometimes several times an hour.

My browser history tells me that I searched “Ghomeshi” 387 times in the 11 months after the news broke. If I had been reasonable, I would have set up a Google alert, undoubtedly saving me hours in lost productivity. But I wasn’t in a reasonable state of mind.

I had always felt that the CBC was the best of Canada: Vicki Gabereau interviewing Leonard Cohen, Peter Gzowski publishing a listener’s Caesar salad recipe (“When you think you have enough lemon, add that much more again“). Having lived in the U.S. for three years, I listened to the CBC to feel at home in Berkeley, to cement my identification with Canada the Cold Socialist Utopia. In the days and weeks following the news — as the CBC flailed in poorly conceived attempts at damage control and Ghomeshi did the same — the realization that my beloved public broadcaster had knowingly harbored an abuser was profoundly disorienting. I was more than heartbroken. I was unmoored.

And I Googled Ghomeshi because I needed a place to go and a thing to do when my memories flooded in. Since the night I had recounted the news of Ghomeshi’s firing to my husband, I had swum in a fog of memory snippets. Strange, offensive, weird, not-normal, and outright offensive sexual flashbacks.

They flickered through my morning meditation, my commute, my sessions with clients, my lunch hour. While feeding breakfast to my one year-old daughter, I remembered being molested by three men at a house party when I was 14. Falling asleep next to my three year-old, a vision of the therapist who touched my breasts invaded my suddenly cringing mind and panicky body. The man who pushed me against a downtown construction wall and called me a whore; the man who slapped me at work and told me to get over it; the man who harassed me at the student newspaper, derailing my desire to write and broadcast for over a decade. When I thought of these things I opened my phone and Googled Ghomeshi’s name. To learn more, to find out more, to hear more stories. To know.

The memories would disappear momentarily only to return and recombine, linking arms like a group of children playing a terrifying, exploitive game of Red Rover. Between November and December of 2014, I wrote down every memory that came to me. I called my therapist and made an appointment for the first time since the baby was born.

“On Thursday I voluntarily showed evidence that everything I have done has been consensual…”

The conversation about consent finally blew up in Canada and from my phone, riding the San Francisco BART train, I read all of it. It felt like each article, each interview, was a lifeline to another woman, bringing me a bit closer to clarity about what had happened to me.

Because it wasn’t just the overtly violent memories that were bothering me. My stickiest memories were of soft coercion: times I had sex when I didn’t want to, and my partner knew it. When friends, dates, boyfriends, ex-boyfriends (screw you, ex-boyfriends) were particularly forceful with their desires or their hands. In some ways, the more violent incidents in my life were less upsetting — less confusing — than those in which I had given, as it is called in the fanfic community, “dubious consent.”

Ghomeshi claimed that he was into “rough sex” and I thought about the times I had been surprised by that, too; when I had not consented to being choked, slapped, or handled so roughly that I bled afterward. I do not identify as a rape survivor and the violence I have experienced never caused permanent injury. But even explicitly nonconsensual hickeys suddenly felt like legitimate reasons for upset. Were these incidents of sexual assault, too? What did it mean that I had so many of these memories, so many moments of distress? Was there something about me, the daughter of a feminist single mom, that invited these violations?

I told my therapist that I wanted to acknowledge, grieve, address, and release each incident. But when I tallied them up, I counted 41 memories. That’s $4,100 in therapy sessions.

I didn’t work through them all in therapy but I haven’t forgotten. I still think about the ways that consent operated in Canada when I was growing up in Vancouver and when I moved to Toronto and then Montreal in the 2000s. I want to know if other women experienced the same things, with the same frequency. I want to feel free of the shame of these moments. I want other people to know. And the only way to do that is to talk about it. A lot.

Today, and over the next month, I’ll share 29 of those experiences here. Each day of February — the month Ghomeshi goes to trial, and the month we celebrate romantic love — I’ll post about another incident in which I, a young, able-bodied, Swedish-Canadian woman with plenty of privilege, was sexually violated. I’ll look at the context for each event, its precedents and successors. The ways I perceive it differently now, from a narrowed and enthusiastic definition of consent. And, because his brave accusers started it all, I’ll even talk a little bit about our disgraced broadcaster, Ghomeshi; and the one who really broke our hearts, the CBC.

***

Today’s entry will be short. I’ll start near the beginning, with incident number two.

I was about ten years old and lived in a rambling Victorian house with my mother and sister in Kitsilano, Vancouver. Back then, it was a middle-class neighborhood full of artists, public housing, grow-ops, and crumbling beach walls. I had a best friend, Nora,* who was a year younger and lived nearby. The selfie not yet having been invented, we spent a lot of our time taking pictures of each other.

In the post-Britney Spears world, it’s hard to see this as unusual, but I think that we were, compared to our peers, very image-conscious. We talked endlessly about shopping, clothes, and makeup. We dressed up in our cutest outfits and posed each other, using an old film camera to document these attempts at femininity.

The photo shop in our neighborhood allowed us to see images of our prepubescent selves in all manner of lovely, pensive poses for the low price of $6.99. We would pick up our photos after the guaranteed maximum 30 minutes, the paper still warm in our hands, and open it right there on the sidewalk. Damaging the still-sticky prints with curious fingers, anxious to see how we looked from the outside.

There was nothing wrong with this. Nothing wrong with cultivating a performative female image, with learning art direction from trial-and-error, with a young woman developing her sense of self in the company of a close friend. Nowadays, tweens with access to technology don’t necessarily have to have their narcissism vetted by adults. But we did, and small comments from our parents (“Are you sure you want to spend your allowance on developing photos?”) let me know that it made the adults uncomfortable.

One day, a man approached us. We were standing at the top of a set of stairs leading down to the beach. It was coldish and there were few people outside. I took a picture of Nora and he came up the steps behind her. I said sorry, apologizing to him for taking up the space of the stairway with my camera frame. I brought the camera down from my face and gestured that he could pass without entering it.

He said that was OK and stood standing where he was. He was wearing tight jogging shorts, fluorescent green (screw you, 1990s) over the first erect penis I had ever seen. I felt my heart in my stomach. Both Nora and I played it cool. I told her we should probably leave. She agreed, we left.

I remember the man’s goofy face, a sort of smile on it. Him wanting his penis and shorts and goofy smile to be in a 10-year old’s photograph. I was careful to be sure he hadn’t succeeded, combing through the photos we picked up from the shop. We told no one and never spoke about it.

I knew instinctively that it would only bring more trouble, more discomfort from the adults around us. There is nothing more fetishized in our society than a young woman exploring her sexuality or nascent womanhood; there is nothing more shamed.

I wasn’t molested that day, or physically harmed in any way. The man didn’t say anything inappropriate. I’m sure that he, like Nora, doesn’t remember it. But it’s a memory that stayed with me, like a warning bell notifying me of the power and danger of having a young female body. It was perhaps the first moment in time where I fenced in my own activities because of the sexual threat of a man. He should have left. But instead, we did.

Tomorrow: #3, being falsely accused of shoplifting by a man who wanted to boink an 11 year-old.

*Names have been changed.

All images: Svea Vikander.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.