A recent photo in French daily Liberation hints at the Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce’s role in facilitating tax avoidance, which is partly an outgrowth of Canadian banking prowess in the Caribbean and Ottawa’s role in shaping the region’s unsavoury financial sector.

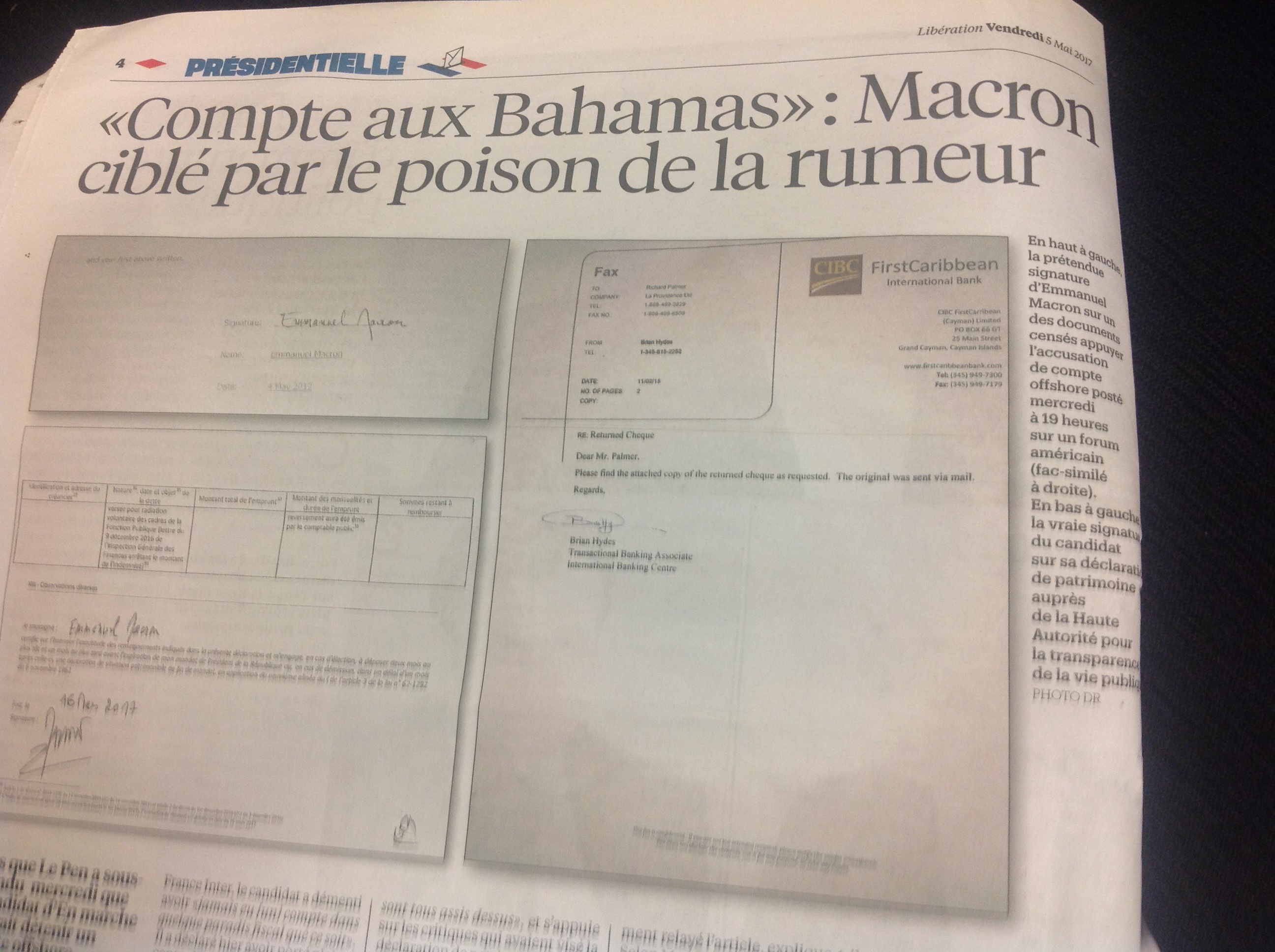

Just before the second round of the French presidential election documents were leaked purporting to show that Emmanuel Macron set up a company in a Caribbean tax haven. The president-elect’s firm is alleged to have had dealings with CIBC FirstCaribbean, a subsidiary of Canada’s fifth biggest bank.

While Macron denies setting up an offshore firm and contests the veracity of the documents, this is immaterial to the broader point. If the documents are a fraudulent political attack, those responsible chose CIBC First Caribbean because it is a major player in the region and has been linked to various tax avoidance schemes.

CIBC registered 632 companies and private foundations in the tax haven of the Bahamas between 1990 and May 2016, according to documents released in the Panama Papers.

CIBC was named 1,347 times in a cache of leaked files concerning secret tax havens released by the Consortium of Investigative Journalists in 2013.

FirstCaribbean was implicated in the 2015 FIFA corruption scandal. To avoid an electronic trail of a $250,000 payment to former FIFA official Chuck Blazer, a representative of FirstCaribbean allegedly flew to New York to collect a cheque and deposit it in a Bahamas account.

In 2013 the U.S. Internal Revenue Service sent FirstCaribbean a summons for information on some of its customers who may have been evading US income tax and the CIBC subsidiary was placed on an IRS list of “financial institutions where taxpayers receive a harsher penalty if they are found to have undisclosed accounts.”

CIBC is apparently popular with wealthy, well-placed Africans. Economist Thierry Godefroy and legal expert Pierre Lascoumes write that the “Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce is known as the bank of many African dignitaries” while French Africa specialist François-Xavier Verschave called it “the nefarious CIBC, favourite bank of African oil dictators.” In 1997, for instance, the Toronto-based financial institution was the conduit of a $22 million transfer from Geneva to the British Virgin Islands for Kourtas, which was owned by Gabonese dictator Omar Bongo.

CIBC is not only the Canadian bank with operations in a Caribbean financial haven. In fact, Canadian institutions dominate the region’s unsavoury banking sector. In 2013 CIBC, RBC and Scotiabank accounted for more than 60 per cent of regional banking assets. In 2008 The Economist reported Canadian banks controlled “the English-speaking Caribbean’s three largest banks, with $42 billion in assets, four times those commanded by its forty-odd remaining locally owned banks.” With their presence in the region dating to the 1830s, Canadian banks have been major players in the Caribbean since the late 1800s.

Going back further, much of the capital used to establish the current incarnation of CIBC came from supplying the Caribbean slave colonies. The Halifax Banking Company was the first bank in Nova Scotia and the founding unit of today’s CIBC. The Halifax Banking Company’s leading shareholder and initial president, Enos Collins, was a ship owner, who made his wealth by bringing high-protein, salty Atlantic cod to the Caribbean to keep hundreds of thousands of “enslaved people working 16 hours a day.” He was also a privateer, licensed by the state to seize enemy boats during wartime, and according to a biography, likely captured and resold slaves in the region.

Ottawa shaped post-independence Caribbean banking regulations. Beginning in 1955, a former governor of the Bank of Canada and director of the Royal Bank of Canada, Graham Towers, along with a representative from the Ministry of Finance, helped write the Bank of Jamaica law of 1960 and that country’s Banking Law of 1960. These laws, which became the model for the rest of the newly independent English Caribbean, pleased Canadian banks.

In The Banks of Canada in the Commonwealth Caribbean Daniel Jay Baum writes, “the overall and firm impression with which one is left after reading the [Bank] Act is that its drafters did not intend to control the foreign operations of Canadian banks, or that if they intended to, they failed to do so.” More to the point, notes Towers of Gold, feet of clay: The Canadian banks, “West Indian banking laws, when they were written, were written with our help and advice and for our benefit.”

Alain Deneault details the work of Canadian politicians, businessmen and Bank of Canada officials in developing taxation and banking policies in a number of Caribbean financial havens in his 2015 book Canada: A New Tax Haven: How the Country That Shaped Caribbean Tax Havens Is Becoming One Itself.

Deneault writes: “Beginning in the 1950s, at the instigation of Canadian financiers, lawyers, and policymakers, these jurisdictions changed to become some of the world’s most frighteningly accommodating jurisdictions. In 1955, a former governor of the Bank of Canada most probably helped make Jamaica into a reduced-taxation country. In the 1960s, as the Bahamas were becoming a tax haven characterized by impenetrable bank secrecy, the Bahamian finance minister was a member of the board of administrators of the Royal Bank of Canada (RBC). A Calgary lawyer and former Conservative Party honcho drew up the clauses that enabled the Cayman Islands to become an opaque offshore jurisdiction.”

Another way Canada has enabled the offshore financial infrastructure is by signing tax treaties and Tax Information Exchange Agreements with Caribbean tax havens. Due to a 2011 Tax Information Exchange Agreement, Deneault writes, “subsidiaries of Canadian companies that record their profits in the Caymans can now transfer them to Canada without paying any taxes.”

While they’ve proliferated in recent years, the first double taxation treaty Canada signed with a Caribbean tax haven dates to Wayne Gretzky’s inaugural season in the NHL. In 1980, Joe Clark’s short-lived Conservative government signed a double taxation treaty with Barbados. This allowed Canadians to park their international profits in Barbados, which taxes companies at between 0.25 per cent and 2.5 per cent, and transfer them here without paying tax in Canada.

Ottawa has actively defended the Caribbean financial system. In response to a push for greater regulation of the offshore world, in 2009 Minister of Finance Jim Flaherty told the Board of Governors of the International Monetary Fund (where Canada represents most members of the Commonwealth Caribbean as well as Ireland): “Some of our Caribbean countries have significant financial sector activities. There is a risk that changes to financial sector regulation in advanced countries could have negative unintended consequences on these activities.

“In particular, there is a risk that measures taken against non-cooperative jurisdictions, including tax havens, could have unintended negative impacts on well-regulated, transparent, financial centres. I believe that this should be avoided. Countries that comply with international standards should be protected from such measures.”

Canada has shaped the Caribbean’s opaque financial sector and CIBC seems to be at the centre of international offshore tax avoidance.

Let’s go Canada! Time to clean up the mess we created in the Caribbean.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.