When Norman Bethune left Montreal for Spain in 1936 to help the Republicans in their doomed effort to hold back Franco’s fascists, he spoke no foreign languages and had no fixed role waiting for him. But he was among a group of determined individuals who believed “if fascism could be stopped in Spain, a larger war would not break out,” and he wasted no time making himself useful. When Bethune left Madrid less than a year later, he had created and implemented a mobile blood transfusion unit, the first of its kind, that treated soldiers right at the front and drastically reduced fatalities. He was also on the verge of collapse, drinking heavily and making enemies on all sides. His friends convinced him to leave Spain and return to Canada to drum up support for the Republican cause — his radical, forthright actions had been both a remarkable success and a complete debacle.

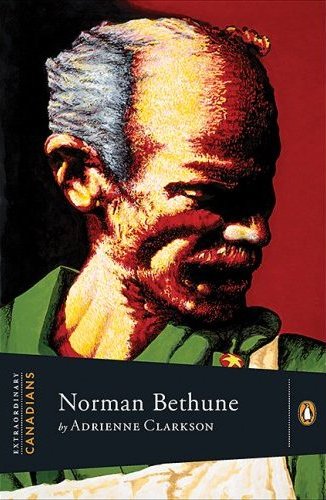

The image of Norman Bethune carefully sketched by Adrienne Clarkson in this contribution to the Extraordinary Canadians series invokes the same duality: the guerrilla doctor, impetuous and irascible, and the humanist committed to alleviating the suffering of others. He was undoubtedly a complex man who alienated many around him. He is also perhaps the most famous Canadian, worldwide, that ever lived.

My fascination with Norman Bethune comes from the most banal of motives — we were born in the same little Ontario town. I grew up visiting the Victorian manse where Bethune was born in 1890 at least once or twice a year. At Christmastime we schoolchildren would visit this staid residence of a Presbyterian minister (Bethune’s father), and marvel at the elegant formality of the parlour, the chair made of papier-mâché, and the quaint decorations of the season: popcorn strings and oranges pierced with cloves. I also worked at the historic house as a teenager, giving tours to the busloads and busloads of Chinese tourists whose reverence of that quiet space was in a different league from our childish wonder. Sometimes I’d observe a Chinese tourist leaning over to take a small clump of dirt from the lawn — a practice, needless to say, that was not encouraged at this or any other heritage site — and the image stuck with me. I burned to know Norman Bethune, and I wanted to own some small piece of his story.

Clarkson credits the harsh landscape around Gravenhurst for shaping Bethune. He “sprang right out of this granite” like a Massassauga rattlesnake, and his appetite for rough, outdoor living stayed with him. “Nature and the Canadian Shield,” she writes, “represented . . . not simply pleasant holidays, they were a fact of his life; he was born close to the wilderness and he could contend with it.” In addition to working in a lumber camp in northern Ontario for a year after high school, he took time off from his medical studies at the University of Toronto to work for Frontier College — labouring alongside immigrant workers by day, and teaching them to read and write at night.

It’s no surprise that Bethune’s life inspired a number of books and films, though not at first. Clarkson likens him to Jerome Martell in Hugh MacLennan’s The Watch that Ends the Night. Martell, she writes, was “clearly modelled” on Bethune, and hearing of his exploits “made it possible for MacLennan to write one of the greatest Canadian novels.” Like Bethune, Martell strides out of the wilderness, builds a successful medical career in Montreal, battles fascism in Europe, and displays a sort of supreme humanism in everything he does like a banner unfurling behind him. Clarkson spins a convincing narrative, but it’s not the whole story. Many would disagree that Martell was based on Bethune, including the author himself. MacLennan’s biographer Elspeth Cameron claims the two men never even met and believes Martell could have been based on a number of other men — including Frank Scott, the husband of artist Marian Dale Scott, who was the “unique love of [Bethune’s] life” and the subject of much scrutiny in the book.

Clarkson doesn’t entertain these inconvenient theories, nor does she acknowledge that Bethune is mentioned throughout The Watch that Ends the Night — as a friend and colleague of Martell, but nothing more. It’s not hard to see why she equates them: Martell as Bethune is a better story. There is a reckless glamour about both men, partly because of their intense volatility. In my own studies of Bethune, the smartly dressed gentleman doctor — who also had tumultuous affairs with women and dabbled in art and poetry — satisfied my desire for a dashing Gatsby figure in bohemian Montréal. Far more so, certainly, than the image of that gloomy church manse we both left behind.

Such dynamic characters inevitably cause discord; they also serve as barometers for the prevailing issues of their era. They remind us of what matters, then and now. Clarkson writes that “Bethune was an example of somebody who, by the sudden decision of his will, could introduce into the course of events a new, unexpected, and transforming force.” What did this translate into? After almost succumbing to tuberculosis, an epidemic that was tearing through both rich and poor at the time (but killing far more of the latter), Bethune fought for socialized medicine and helped form the Montréal Group for the Security of the People’s Health. In a city where two-thirds of the population was on some sort of relief, he started a free medical clinic in the suburb of Verdun on Saturdays. He railed against profit-making in medicine, stating “Medicine, as we are practicing it, is a luxury trade. We are selling bread at the price of jewels . . . Medical reforms such as limited health insurance schemes are not socialized medicine. They are the bastard forms of socialism produced by belated humanitarianism out of necessity.” The writing was soon on the wall. Bethune stepped forward to revolution; the political leaders and medical community who might’ve championed him stepped back.

Bethune joined the Communist Party in 1935 before travelling to Spain and then China. According to friends, the decision arose from his need to prove “the difference between bohemian gesture and revolutionary dedication: between theatrical posturing and affirmation of life.” Clarkson writes of how his decision to join the Party “tarnished him in many eyes . . . he was neglected, nearly forgotten, in his own country before 1971 and the beginning of Canada’s diplomatic relationship with the People’s Republic of China.” Meanwhile, in China he was revered by millions. His selfless commitment to Mao Zedong’s Eighth Route Army led Mao to write an essay on Norman Bethune that was memorized by schoolchildren across the country. The two men even met once in 1938; an encounter that Clarkson renders nicely. Bethune’s term as a field doctor for Mao’s army ended abruptly the following year — he died in a tiny, war-ravaged village after contracting blood poisoning from operating without gloves. From determined individualist to Communist, in the end he died virtually alone.

Clarkson’s story of Bethune ends there, but much of how he is remembered in his native land came from decisions made more than thirty years later as a result of Canada’s burgeoning relationship with China. In the 1970s his birthplace in Gravenhurst became an historic site, Montreal unveiled a statue of Bethune near Concordia University, and various dramatic series and biographies came to fruition. Clarkson’s book doesn’t explore these diplomatic acts of remembrance, and confuses some small but basic details. She repeatedly mistakes his date of birth as March 4th, for instance, when it is the 3rd, and states his Montreal statue is at the corner of Dorchester and Guy streets, when it is actually at de Maisonneuve and Guy. These are just two oversights, of course, in a little book that is crammed with detail, but it’s hard to ignore such discrepancies in a story I’ve been steadily devouring since childhood.

For all of my proprietary airs when it comes to Bethune, I don’t think I would have much liked the man had I met him. I also doubt his mercurial temperament would feature in any judgment of him if he weren’t remembered chiefly as a Communist. In Canada, his fight for socialized medicine was loud and unequivocal. He made the status quo appear so unjust that it was soon deemed inhumane. As an international humanitarian, the sheer scope of his actions was extraordinary, as was his selflessness. He determined where his help was needed most and set off quickly in that direction. In The Watch that Ends the Night, MacLennan writes of Martell’s return to the grey Canada of the 1950s, embodying all the passionate ideals of the 1930s that had come to nothing.

One wonders what would’ve happened if Bethune came back, if he’d strode in from the wilderness once more and reminded us who we were and what we thought was important — if we’d listen.–Tara Quinn

Tara Quinn is a Toronto-based writer and Assistant Editor at Brick magazine.