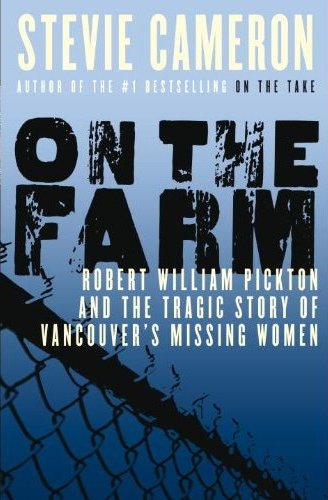

Stevie Cameron’s On the Farm: Robert William Pickton and the Tragic Story of Vancouver’s Missing Women, was published last August after the Supreme Court upheld Pickton’s multiple-murder conviction and lifted a publication ban. Cameron sat down for an interview on Oct. 6 while in Vancouver to give a talk in the Downtown Eastside, the troubled neighbourhood from which many of the missing women were abducted.

Cameron is a Toronto-based investigative journalist whose previous books tackled political corruption under Mulroney, as well as his involvement in the Airbus scandal. She has written about politics for the Ottawa Citizen and the Globe and Mail, and hosted The Fifth Estate on CBC. In 1997, she founded Elm Street magazine and assigned the story of Vancouver’s missing women to reporter Daniel Wood.

Until 1997, women had been disappearing at a rate of one to five a year. Between 1997 and 1998, that rate spiked to one or two a month. In the town of Coquitlam 30 km east of Vancouver, meanwhile, people were talking about Robert William Pickton (“Willie”). Friends were finding purses and women’s i.d. cards in his trailer and telling the police that Pickton may be connected to the disappearances. In late 1997, Sandra Gail Ringwald, whose real name is under a publication ban, escaped Pickton with severe stab wounds. She was interrogated by the RCMP. But the police didn’t identify Pickton as a serial killer until 2002.

Pickton confessed to 49 murders. The police charged him with 26. On Dec. 9, 2007, he was sentenced to life in prison for murdering six women. Wally Oppal, B.C.’s former Attorney General, was recently appointed to head the Missing Women inquiry into the botched police investigation.

On the Farm‘s thoroughly researched portrayal of Pickton’s modus operandi and of the women’s final days makes up for decades of silence. But the gruesome descriptions sometimes verge on sensationalism. This paradox emerges in Helen Polychronakos’s interview with Cameron who, while fighting to speak truth to power, can’t resist the lure of a good story.

You went from writing about rich and powerful people like Mulroney to writing about some of the country’s most disenfranchised, the women of Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. What was it like, shifting gears like that?

It was actually a simple move for me because I was sick of politicians. For 17 years in Toronto I had run a shelter with a food program for homeless people at my church. I have a background in dealing with very troubled, addicted, poor people. So when my agent said, would you be interested in [the Pickton book]? I said, you bet.

What was your biggest challenge in researching the Pickton case?

Having to do it in Vancouver. [Laughs] That was also the attraction. The biggest challenge was not that I was here but that it took so long. I learned a lot about Pickton because I went to the preliminary hearing in Port Coquitlam and that lasted seven months. And then the voir dire started. It was a year of arguing about the evidence. The defence won a huge number of their demands.

What kinds of evidence did the voir-dire exclude?

The testimony of Sandra Gail Ringwald, because the defence convinced the judge that she was not a reliable witness. This was a woman who was stabbed 15 times. She would have testified, but at the voir dire, the defence won everything they wanted. They got it down to six cases. Much easier to win on six than on 26. They threw out “Jane Doe,” which I thought was a tragedy. She was the only one they didn’t have a name for but the evidence was incredibly strong.

Your biggest critique in On the Farm is against the Vancouver Police Department. What responsibility do they bear in allowing this tragedy to continue as long as it did?

They’ve admitted that they have a huge responsibility. They ignored the women and didn’t put their efforts into it. They had a man who was eventually convicted of having child pornography on his computer, and he was in charge of the missing persons unit. Part of the reason that they didn’t want to do it is that they didn’t want to go along with [former VPD officer and geographic profiling expert] Kim Rossmo’s theory that there was a serial killer out there. [Rossmo] said to me, listen, they didn’t know how to do it. They didn’t have the know-how to handle a massive serial killer investigation like the one they were about to face. It was much easier to say, the women are on holiday.

Do you think the VPD is the only police force that neglected the women? What about the RCMP, who have jurisdiction in Coquitlam?

Most of the women were based in the DTES. The RCMP were the police in Coquitlam, and they did try to get a search warrant because he was a suspect between 1997 and 1999. They followed him around for a while. They were getting tips between 97 and 99 that he was the one. The regional crown counsel wouldn’t give permission for them to do a search of the farm, because he said they just didn’t have enough evidence.

When they finally did get a chance to have a search warrant for the farm, they didn’t take any chances. This is the “Rookie Cop” chapter, which is quite a lot of fun. A guy called Nathan Wells testified, and he’s a rookie. He’s dealing with small-time drug dealers in Coquitlam.

[Pickton’s acquaintance] Scott Chubb, who needs money to buy diapers for his kid, says he can hand Wells some drug dealers. Wells says they know who they are. So Chubb says well what about illegal weapons? What’s that worth? [Wells] says, what kind of illegal weapons? He says, illegal weapons on the Pickton farm. Willie’s got some guns. Willie was flagged as a suspect in [the missing women] case.

So the moment that Nathan goes back to work, puts it in the computer, the RCMP says Whoa! [In Pickton’s trailer] they find women’s i.d’s, bloody clothing, stuff. Lots of stuff. When Willie drives up, they land on him on the front porch, take him down, you’re under arrest, and take him away.

The RCMP had been getting tips from Willie’s friends. Bill Hiscox for example. That’s why he was already flagged as a suspect. How long had they been getting these tips for?

Well Hiscox was fairly early on. He got it from Lisa Yelds. Lisa had been Willie’s best friend for years. She was deeply suspicious of him. And she told Bill, she said, Billy, you have to call the cops or something, I’m sure Willie’s killing these women. And he did but nothing happened! Not even in 1997.

After you worked on the Mulroney/Schreiber book, you were accused of being an RCMP informant. The RCMP said that you were, and then they withdrew that claim. Eventually you were exonerated. But did it at all affect your investigation with the RCMP in Coquitlam?

The only thing I ever had to do with the RCMP in Coquitlam was that they were at the trial. My cousin, Jamie Graham, was the chief of police in Vancouver, so I couldn’t have anything to do with the VPD.

In the Pickton case, you didn’t need information from the RCMP?

No, but given what I’d gone through there was no way I was going to ask them anyway.

After Sandra Gail Ringwald was attacked in 1997, the RCMP interrogated her and searched Pickton’s trailer. Didn’t they find anything suspicious?

They found a lot of blood. I don’t know what kind of search they did. He was charged with attempted murder in 1997. He killed 13 women that year. [Ringwald] would have been the fourteenth. They probably had no idea. She was afraid to testify against him, so she didn’t come to court, and that’s why the charge was dropped.

And that case didn’t lead anywhere? It didn’t give them any clues that this was a serial killer?

No. And that’s probably why they are starting the inquiry [into botched police work] in 1997. But I believe that they should start this inquiry much further back.

Ideally, if you could direct this commission into the police investigation, how would you do it?

You bring back all the people that tried so hard to do something about it. There was Kim Rossmo, the best expert in Canada on serial killers, and the [VPD] fired him. I would have looked at all the memos and the failed efforts, all the paper work on this. You’ll find there’s almost no paperwork on this. Try to talk to all the police officers responsible at the time, and you’ll find they’ve all almost all disappeared. They retired, even before Jamie [Graham] took over to clean it up. The main inside info I got about the Pickton case comes from the preliminary trial and the voir dire. I had the transcripts.

Let’s talk about the women now, because you’ve said that the focus of this book is to give the women voices.

No, no. It’s not that. What I’ve done is that this is the only place where all the women are named and what happened to them is described. And I knew that if I didn’t do that nobody would. They were ignored. Nobody gave a damn about them except their families and some police officers and some journalists. So, once the judge severed the counts, got them down to six, suddenly those women were just as invisible as they had always been.

We’d had hope, that their stories would be told, and suddenly they were just shoved aside yet again. And I thought, somebody has to show the mounting horror of one death after another after another. Tell the stories of the last days of their lives. I was able to do that in many cases because witnesses came and testified about when they last saw this person and what she was like.

It was very difficult to read all that. How were you able to go back to it day after day? I had to put the book down several times.

People have to know that they were people’s daughter and sisters.

What do the women’s families think about the book?

It’s so new. I’ve met one family, Dianne Rock’s, who were in Colborne, Ontario when I was speaking there. I think a lot of families have been terrific. It think some of them are shocked. I mean last night I had dinner with Rita Ens who was the victim services worker whom I adore. She was shocked by what I wrote about her background. She said she wasn’t expecting to see that in the book. That she was sold for a bottle of beer, that she was sexually abused by her father.

Do you ever worry that these stories might be exploitative?

I worked hard to make sure that didn’t happen.

How?

Well, I just wrote it straight. I did this book with a lot of love. And I think people know that.

None of the families were upset that you were revealing so much information?

It’s already public on the website. Wayne Leng [friend of Sarah de Vries, who disappeared in 1998] is responsible for much of that. Anybody can read that stuff.

What do you think of the DTES today? What is the greatest barrier to safety for women working there?

Poverty. Poverty is terrible. And lack of drug treatment. They get sent to these recovery houses in Surrey or wherever after they’ve been through detox-if they can get into detox. Millions of dollars have been poured into the DTES but the lack of rehabilitation centres, the lack of treatment, the lack of good detox, the lack of good housing… They still live in these hotels where if you want to go visit them you have to pay the guy at the front ten bucks. Nothing’s changed.

What’s their greatest hope?

I haven’t got an answer for that. It is a community. In Toronto, we don’t have anything like the DTES. We have a DTES all right but it’s in tiny little pockets all over the city. I haven’t seen much change in Vancouver. I see the change in the developers, because there is such great housing potential there. And maybe that’s its great hope, that they demolish it because it’s too valuable for poor people. And if they get rid of it…I don’t know what’s worst, getting rid of it or keeping it because it’s a community. I’m very torn.