It’s still not easy growing up indigenous in North America today.

Although residential schools and the mass adoptions of indigenous kids during the Sixties Scoop are in the (not-so-distant) past, decades of systemic racism and government policies of exclusion have taken a toll on this continent’s first peoples. The result is high numbers of indigenous people in North America living with generational poverty, substance abuse and family violence. Even being treated fairly in school is a struggle, when many educators expect less from indigenous students than their peers.

Two new books hitting the shelves this summer deal with these struggles from the next generation’s point of view. Tilly: A Story of Hope and Resilience is part autobiography, part community healing exercise for author Monique Gray Smith.

The book is “about 70 to 75 per cent” of Gray Smith’s life story as a Lakota, Scottish and Cree woman raised in British Columbia. Embodied in the titular character Tilly, Gray Smith details how she was able to overcome her parents’ divorce, the loss of her grandmother, substance abuse and fear of personal failure to discover more about her culture and herself.

“For me, the intent [of Tilly] is that people will read it and understand our history through a lens of resilience and begin to realize some of the things that have occurred in this country, that continue to influence indigenous people, were really traumatic,” Gray Smith said in an interview.

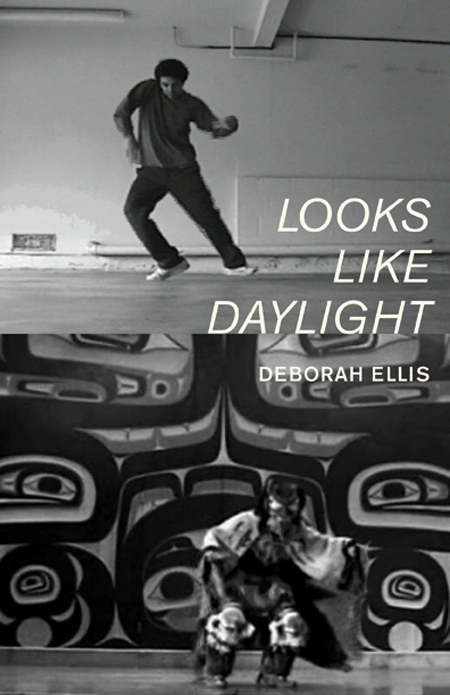

Looks Like Daylight takes a broader view of indigenous struggles in North America. Author and journalist Deborah Ellis interviewed over 40 indigenous children, nine to 18 years old, asking them to summarize their experience growing up indigenous.

From youth with a deep connection to culture and community, to those raised by strangers outside of their heritage, to others struggling with substance abuse and violence in their homes, Ellis provides a platform for these kids — often the most marginalized and voiceless in our society — to tell their own story.

Although not indigenous, Ellis says the book comes at an interesting time in the dominant culture’s history. “People like me who’ve not been part of that community, we really have no excuse for not knowing what was going on in the past generations to these folks. We have the benefit of both being able to look at that history, and the benefit of being able to talk with folks who are going to lead us into the future.”

Universal stories

Tilly’s protagonist may have grown up in B.C. during the 1980s, but she experiences many of the same troubles indigenous youth face today. Her parents struggle to find well-paying work and must move their family multiple times, separating their daughters from supportive friends and family.

It has an especially bad effect on the sensitive Tilly, who has trouble making friends. Feeling alone in a world she doesn’t understand, she turns to alcohol at age 12. The journey to sobriety and self-acceptance takes decades, and is helped and hindered by a cast of characters.

Some of Tilly’s characters are people Gray Smith met in real life, while others are used as stand-ins for telling stories about indigoes people that the author thought were important to cover, but not hers to tell — like the experience of those who attended residential schools, or were affected by the Sixties Scoop.

One of the characters who didn’t make the book is Gray Smith’s own partner, Rhonda. Instead — spoiler alert — Tilly’s romantic interests are all men. Gray Smith says it was a tough decision, but she wanted readers to focus on what her book teaches young people about First Nations in Canada.

“I know in this country, had Tilly had a relationship with a woman — or in the United States, even more so — that people would not read the book because of that,” she said. “Maybe even in five, 10 years, it wouldn’t have mattered. In the western part of our country, it may not matter, but in other parts of our country, it still matters.”

A history through story

Tilly was originally released as a shorter, self-published book called Hope, Faith & Empathy in 2011, but it was actually 20 years in the making. Just six months sober in 1992, Gray Smith was encouraged by someone interviewing her for a spot in the University of Victoria’s School of Social Work to write her life’s story.

“Just as I was standing up to leave, one of the ladies who interviewed me said, ‘I look forward to reading your book one day.’ And I turned around and said, ‘Pardon?’ She said, ‘You’re a really good writer, and I look forward to that,'” she remembers.

Gray Smith says she wasn’t able to conceive of her future as a novelist at the time. But, as she put it, a “seed” was planted within her, though it took another 17 years for it to sprout.

After selling 1,200 of the first edition on her own, Sono Nis Press offered Gray Smith a publishing contract in 2012. The publisher also paired the budding author with editor Barbara Pulling, whose CV includes editing the 2012 Giller Prize winner 419 by Will Ferguson, and acclaimed works by First Nations authors Richard Van Camp and Richard Wagamese.

Out in bookstores and available online through Amazon in the U.S. and Canada this month, Gray Smith hopes the book finds its way into high school classrooms, too, and not just in First Nations-centred courses.

“I’d love it in English or social studies, or history, or someplace else where people can learn history through story and ask questions,” she said, adding the Greater Victoria School District has already pre-ordered copies of Tilly.

“[During] World War II, we had over 40,000 people in this country move from land-based communities to urban settings because of enfranchisement. So how does that impact families’ connection to their land, to their community, to their language, to their culture, to their medicines, to their food? I’d love those kind of critical-thinking, reflective questions to be part of conversation in school.”

‘They all astounded me’

Looks Like Daylight wasn’t Deborah Ellis’s first foray documenting the lives of marginalized youth. A bestselling Canadian author known for her young adult Breadwinner series, Ellis had already published books of interviews with youth in places like Afghanistan, Iraq and North America.

But this is her first book on Indigenous youth in North America. It was an eye-opening experience for the otherwise worldly author.

“I like to think that I’m a fairly aware human being,” Ellis said in phone interview from her home in Simcoe, Ontario. “But I realized that I knew very, very little [about indigenous people]. The kinds of crimes that were committed against their communities, I hadn’t any real idea of the scope of them. The incredible variety of communities and nations and situations, I didn’t really have any good concept of that, either. So it’s been a fantastic learning experience for me.”

Starting in 2009, Ellis travelled all over the United States and Canada interviewing “lots” of youth. The process took two years, and she ended up with way more interviews than she could fit in the 245-page book. Instead, she selected interviews that were geographically and situationally diverse.

Some stories are uplifting, like that of 11-year-old Ta’Kaiya, a young Coast Salish girl living in Vancouver, B.C., whose strong connection to her family, language and culture leads to her passionate environmental activism against the Northern Gateway pipeline.

Or 18-year-old José, whose move from a Dallas, Texas, public school to a Choctaw nation school in Mississippi helped him get top grades and reconnect with his culture.

Others are heartbreaking, like Valene’s, an 18-year-old Cree woman living in northern Ontario who was passed around foster homes since she was five years-old, facing abuse and neglect from countless adults who were supposed to protect her.

For each interview, Ellis writes a preamble connecting the youth’s story to larger changes and challenges facing indigenous people, whether they’re historical facts about the General Allotment Act of 1887’s enforcement of European agricultural practices on Native Americans, or current statistics like the high suicide rates for indigenous youth.

Like Gray Smith’s Tilly, Ellis was impressed by the resilience she found in both the youth and their parents.

“One of the things that I found very intriguing was the way that many are using traditions to get back to the core of who they are. Folks who have been like families, who have been spread apart because of the Sixties Scoop and so on, [are] finding their way back to each other. How powerful that is for the kids today, to have had their parents go through that and come back to their traditions,” she said.

“They all astounded me.”

Room for many storytellers

With the exception of the preambles and the introduction to the book, Ellis and her editors tried to keep bias out of Looks Like Daylight as much as possible. However, bias is unavoidable for any journalist, and Ellis hopes her non-indigenous background will help draw in other readers.

“I’m white, so I wrote it with a sort of white eye, and I hope that there are two kinds of folks that read it: folks that generally don’t have a connection to the community, who know very little, and who can read the book and see what amazing kids these are and learn from that; and the folks who are a part of those communities who read the book, I hope they will see themselves reflected in it and feel respected by it,” she said.

Both Ellis and Gray Smith would like to see more indigenous people — especially women, in Gray Smith’s case — tell their own stories. With more indigenous media outlets, like the Aboriginal Peoples Television Network, SAY Magazine, websites like Redwire Magazine and other outlets for indigenous comedians, artists, musicians and actors, it’s getting easier for youth to put their own expressions and experiences out into the world.

But Gray Smith believes there is need for books like Ellis’, too, as a vehicle for indigenous stories that for whatever reason can’t come out on their own. For her, it all comes down to the author’s intent.

“The more we can tell our stories, in our voice, in many ways that’s where the power of the story resides. And at times we need another voice to share that story,” she said.

This review originally appeared in The Tyee and is reprinted with permission.

Katie Hyslop reports on education and youth issues for The Tyee Solutions Society. Follow her on Twitter.