Like this article? Chip in to keep stories likes these coming.

“The master laughs at the consciousness of the slave,” wrote Frantz Fanon. “What he wants from the slave is not recognition but work.” Recorded in the footnotes of his influential work Black Skin, White Masks, this statement by the anti-colonial Algerian thinker was meant to refute Georg W.F. Hegel’s famous philosophical concept of the dialectical relation between master and slave.

Over 60 years later, Yellowknives Dene scholar Glen Coulthard presents us with a renewed understanding of Fanon’s relevance, this time in the context of a liberal-democratic settler state that occupies nearly one million square kilometres of Turtle Island: Canada.

In contemporary Canadian politics, the word recognition evokes progress for Indigenous nations and people through land claims processes and official gestures like Stephen Harper’s 2008 statement of apology to residential school survivors.

Yet, just over a year after expressing condolences to survivors of Canada’s genocidal policies, Prime Minister Harper publicly denied that Canada had any history of colonialism at all. Less than five years after the apology, the government passed Bill C-45, unilaterally undermining treaty rights and granting increased state access to Indigenous lands and resources.

Canada doesn’t want a mutual relationship of recognition or reconciliation, proposes Coulthard. It wants land and resources.

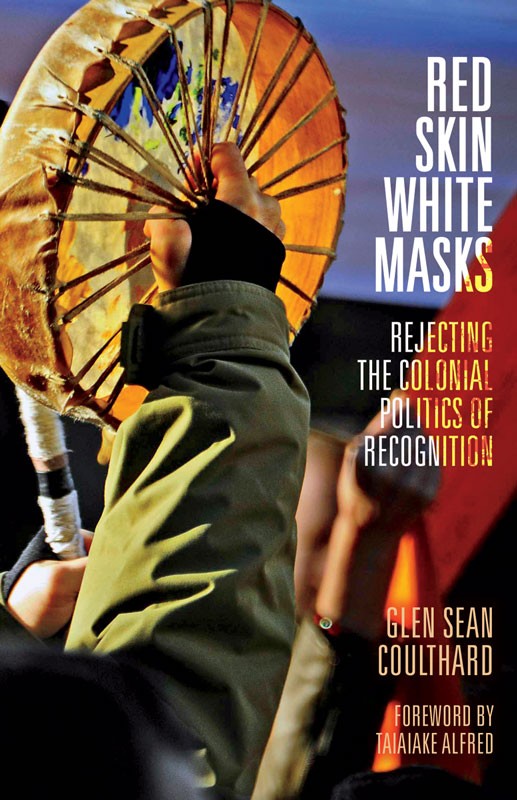

Coulthard’s book Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition begins by explaining how the liberal recognition paradigm in Canada came to replace the more overtly genocidal framework that preceded it.

Up until the federal government’s introduction of their 1969 white paper, Canada’s Indian policy employed explicit strategies of “exclusion and assimilation,” including the reserve and residential school systems and the sexist provisions of the Indian Act that robbed Indigenous women of their rights to land and community. The eventual goal of these policies, says Coulthard, was the complete eradication of Indigenous peoples, if not physically, then “as cultural, political, and legal peoples distinguishable from the rest of Canadian society.”

The rise of Red Power movements in the 1960s and 1970s forced Canada to mask its barefacedly colonial regime with a model centred upon claims of recognition, inclusion and reconciliation. Red Skin, White Masks is premised on the argument that this shift is not a progressive step toward Indigenous freedom and autonomy but rather an adaptation on the part of the colonial system. Overt assimilation is no longer acceptable, so the state has recast its genocidal goals in the palliative language of liberalism.

Coulthard rereads Marx in a settler-colonial context to identify how the expansion of capitalism in Canada is contingent upon ongoing questions of land rather than labour alone.

Land, Coulthard explains, is not only the foundation of all Indigenous life, culture and economics, but also a system of reciprocal relationships and a vehicle for learning how to practise egalitarian coexistence. This system of mutuality, which Coulthard terms “grounded normativity,” calls into question the validity of Canada’s land claims processes, since they presume the dominance of Canadian law over the self-determination of Indigenous peoples and impose a racist assumption of cultural superiority by reducing the complex relations between land and people into the language of property.

Shifting Marx’s analysis from labour to land, explains Coulthard, does not refute the importance of class struggle, nor does it replace class with colonization as the root cause of all other oppression. Rather, it seeks to illuminate how ongoing colonial dispossession is integral to capitalist accumulation and inextricably linked to the oppression of other subordinated groups as well as non-human forms of life.

Coulthard gives great attention to the role of gender-based oppression within Canadian colonialism and the liberal politics of recognition, setting an important precedent that other male radical thinkers will hopefully follow.

In a detailed exploration of Canada’s ongoing use of structural and direct violence against Indigenous women as a tool of colonialism, Coulthard eviscerates the liberal ideology that sets women’s rights in opposition to collective rights or the self-determination of cultural groups. This zero-sum framework has been used not only by liberal feminists but also by Indigenous critics who wish to discredit the activism of women in their own groups as “untraditional.”

While Coulthard doesn’t altogether reject the use of legal mechanisms in service of the rights of Indigenous women, he forces us to question “the implications of turning to the state as a protector of Indigenous women’s rights if the state itself constitutes the material embodiment of masculinist, patriarchal power.”

Like patriarchy, colonialism demands passivity and meekness on the part of the oppressed, a quiet endurance of continual abuse. These power relations delegitimize anger about injustice, framing it as irrational and pathological.

Within the recognition paradigm, Coulthard explains, anger and resentment toward the abusive settler state are perceived as dangerous and counterproductive tendencies to be placated through further state-facilitated reconciliation and institutional accommodation.

In the chapter “Seeing Red: Reconciliation and Resentment,” Coulthard insists anger can be used to spur people to action when it is understood and harnessed appropriately. Like Fanon, Coulthard knows that emotions alone can’t free an oppressed people but that understanding one’s hatred of the oppressor can be a vital turning point through which oppressed groups externalize “that which was previously internalized.” Righteous anger allows the oppressed to purge themselves of the negative self-concept that colonialism has so thoroughly ingrained into their being.

In place of the liberal politics of recognition, Coulthard calls for a resurgent politics of self-recognition. Drawing upon the work of Kanien’kehaka scholar Taiaiake Alfred and Anishnaabe feminist Leanne Betasamosake Simpson, Coulthard discusses a diverse array of collective and individual paths to self-affirmation and self-nurturing that Indigenous people are undertaking. These resurgent practices seek to render an asymmetrical relationship with the Canadian state irrelevant and obsolete.

Connections between diverse social and political movements are of central importance to Coulthard, who sees Indigenous struggles as necessarily linked to feminist, LGBTQ, ecological, labour and racial justice struggles, especially within an anti-capitalist framework. Connections between differing tactics are equally important, from the militant direct action of the warriors at Elsipogtog and other blockades to the creative works of Indigenous artists and intellectuals. The resurgence is well underway and ever growing.

Red Skin, White Masks is not only a landmark contribution to political theory, it is also a call to action. “For Indigenous nations to live, capitalism must die,” concludes Coulthard. “And for capitalism to die, we must actively participate in Indigenous alternatives to it.”

Kelly Rose Pflug-Back is an award-winning writer whose work has appeared in the Huffington Post, Toronto Star, CounterPunch, Canadian Woman Studies, Ideomancer, and The Feminist Wire. Her first book of poems, These Burning Streets, was published in 2012.

This review originally appeared on Briarpatch Magazine and is reprinted with permission.