Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Lisa Bird-Wilson knows how to make words cut and sting.

In her debut poetry collection The Red Files Bird-Wilson skewers government attempts at an apology for residential schools.

“You sowed these seeds and you

apologize for having done this

thing that is still in the doing”

In Burning in this Midnight Dream, Louise Bernice Halfe takes on residential school stories, and other tales of injustice at the hands of Indian Affairs, in a profoundly personal way:

“This afternoon I have my hearing

For Truth and Reconciliation.

I must confess my years of sleeping

In those sterile, cold rooms where the hiss

Of water heaters were devils in the dark

I want to walk these thickets

To that far horizon and not look back”

Both these poets work to address the past and present realities of Canada’s relationship with Indigenous peoples through their poetry. They express anger at colonizers and compassion for the oppressed. They are hopeful but not blindly hopeful — the realities of history are deeply impressed upon the reader.

However, these books differ when it comes to form and style, coming to similar conclusions through very different lenses.

Burning in this Midnight Dream tackles the past through the personal

Halfe’s book begins as a memoir. From the start she invites the reader into an intimate space:

“Sometimes the end is told before the beginning

One must walk backwards on footprints

That walked forward

For the story to be told

I will try this backward walk.”

From here Halfe does take us back, back to her childhood, and to the childhoods of her father and mother, and back all the way to the early settlers, men in black robes carrying the crucifix, “armed with laws, blankets and guns.”

This is a startling way to begin a story for me personally as the product of early French Canadians I sometimes hear tales of how my ancestors “built this country.” No one ever wants to acknowledge the destruction they left in their wake.

Halfe acknowledges it in a lyrical, personal, and engaging way. She isn’t sure what happened to her parents but she can imagine it.

Her mother went to St. Anthony’s Residential School and her father to Blue Quills, an Albertan residential school that is now a First Nations owned and operated college. Halfe herself spent time at Blue Quills when it was a residential school.

Her stories are memories of a chaotic homelife. “We were the children/that mother and father tried/yes tried to raise,” she tells her readers. She writes memories of parents and siblings fraught with conflict and pain.

In “Residential School Alumni,” she remembers the fates of a family: an uncle who shot his wife. The son who died in Vietnam. His brother who died in a police chase. Another brother lost to addiction. And the final brother left alone. “I remember them,” Halfe says and the strength of the account is in it’s simplicity. She does not judge or interpret, just lays the facts of lives and stories in front of us and leaves it to her readers to interpret and try to understand on some level.

In a chilling piece called “The Reserve Went Silent,” Halfe imagines the empty spaces left when “the pied piper played his organ through the reservation.” It’s something her parents never spoke of she says — so she’s speaking of it now.

In her final poem “Owners of Themselves,” Halfe wishes for every teller at the Truth and Reconciliation commission to have two grandchildren beside them as they speak “so they could support the old people as they fell into the dark holes/of memory/and so they also could start to draw the lines that connected sense of self/of those grandchildren to the lives of the old people.”

That’s what this collection seems to be about in the end — a Cree writer shaping her own narrative, taking ownership of her own history and revealing her own story on her own terms.

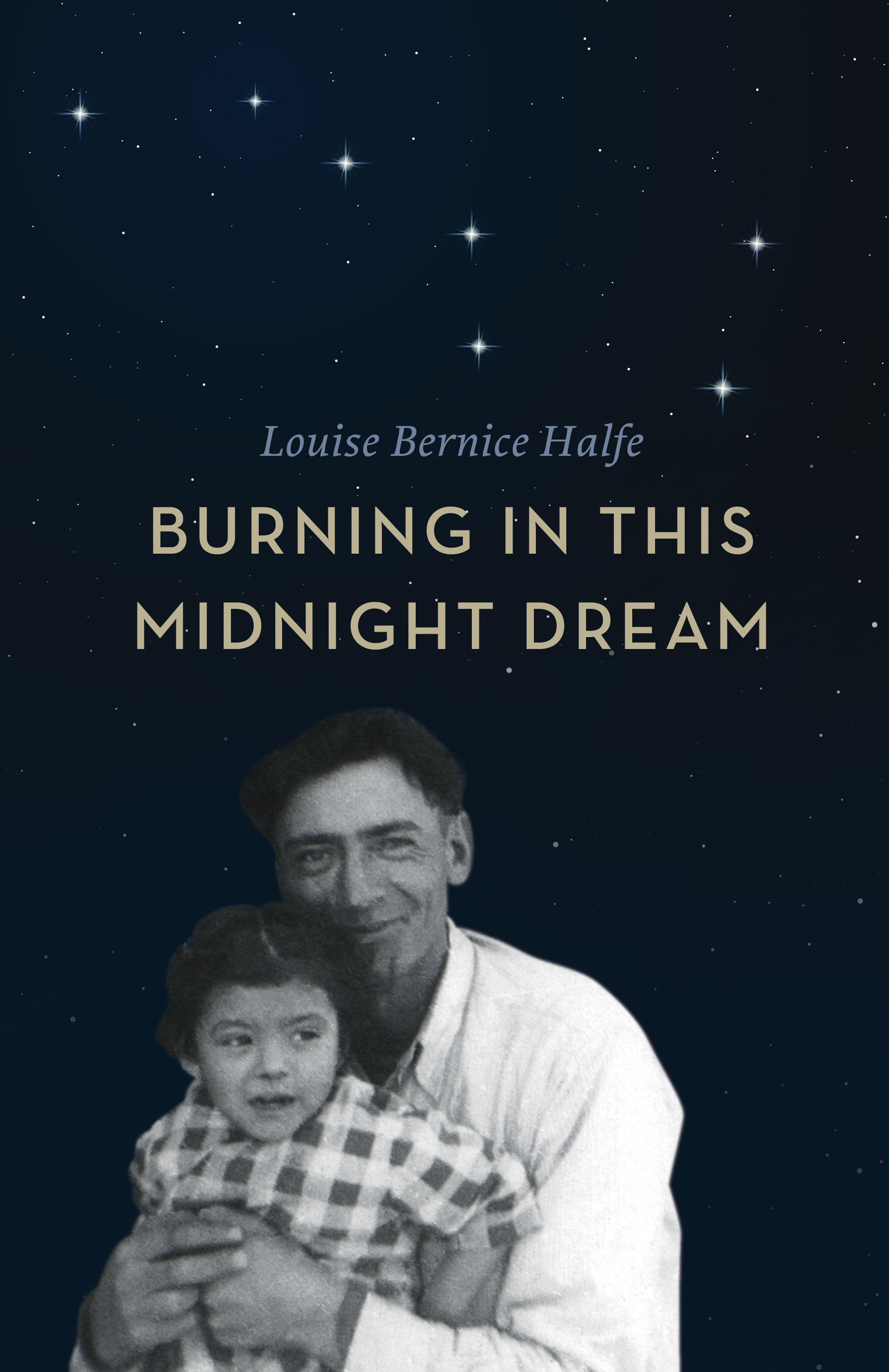

Halfe weaves in and out of recollection and memory to more abstract and fragmented poems. She also includes actual photos of the people whose stories she tells — her father, mother niece and herself as a child all appear on the pages in black and white making the reality of the narrative hit home for the reader even more effectively.

Halfe acknowledges the pain of repeatedly telling these stories, but decides that “It is better to dance with memory/than be noosed by the gut.”

But when dancing with memory one shouldn’t be alone she concludes.

The Red Files personifies the forgotten tragedies

While Halfe’s book opens on the deeply personal, Cree-Metis writer Lisa Bird-Wilson’s book begins with an anonymous residential school experience.

The first poem “Mourning Day,” is about the children who would have sat to have their long braids cut off by teachers, a symbolic gesture of cultural denial and rejection.

Bird-Wilson personifies the braids, saying they “remember the women,” and acknowledging them as “clipped connections/to mothers, kohkums or aunties.”

It’s a fitting beginning. Bird-Wilson uses residential school archives — divided into “black files” and “red files” to delve into this part of Canadian history and her own family history as well. Much of the story is told through the eyes of anonymous children in archival photos.

In the arresting “Girl with the Short Hair” Bird-Wilson questions the forgotten identity of one particular child in a photo. “I might say the short-haired one but they’ve all got short hair and she’s more than that anyway,” she says, calling the reader back to those opening moments of hair cutting.

“She has a name but history hasn’t recorded it,” Bird-Wilson reminds us before describing this girl as “the one with the easy stance left shoulder dropped carelessly… she might turn at any moment and run,” not away from the school but “because it’s in her bones to lope under the prairie sky.”

The girl has no name but by the end of the poem “there she is the breathless one/the one with the wind knotted hair.” The structure of the poem itself which has few lines breaks and carefully placed pauses further emphasizes the freedom and spirit of this anonymous girl whose name history forgot.

When hearing about injustice and tragedy on a wide scale, especially tragedy we perceive as being in the past, like residential schools it is easy to dehumanize and depersonalize victims.

Bird-Wilson fights this tendency by insisting on creating identities for the children in the photos even when their names aren’t remembered. She captures moments of friendship and solidarity and breathes life into instances of pain, sexual abuse, loneliness and longing for home.

An inventively structured piece called “The _____ situation,” tells the tale of a school on a reserve through censored omissions: “_____ was responsible for making the girl ______ pregnant while he was employed by us.”

She names “sixties poached babies,” “stolen women,” and mothers under boil water orders, connecting tragedies of the past with the current state of Canadian indigenous communities. “No, ticklish man, we are sorry, doesn’t drive a stake through the heart of the monster,” she says.”

The final poems of the book seem to be a reconciliation for the narrator as she imagines a deceased relation unfettered and dancing “on the graves of the dead bastards/the ones who have it coming because if you don’t, who will.”

Overall this is a narrative of aggressive and insistent life in the face of cultural oppression and colonization.

“I can hold in the palm of my right hand

all that I have left: one story gift from an uncle

a father’s surname, treaty card, Cree accent echo, metal bits, grit —” she says,

“and I will still have room to cock a fist.”

Experiencing residential schools through the eyes of poets

Canadians are used to hearing about our residential school history in dry factual terms. It’s a very different thing to experience this story through the eyes of skilled poets.

Narratives like these are important because they remind us of the diversity of experience among Canada’s Indigenous people. In comparing these two books that fact is emphasized and will hopefully remind the reader not to generalize or homogenize Indigenous experience in Canada (if they are prone to do so).

Neither books are perfect. The strongest sections of The Red Files are those opening portraits of the children. However, it loses some of it’s power in the later sections. And, as a reader I found myself sometimes lost in the drifting chronology of Burning in this Midnight Dream — although perhaps that’s what Halfe wants.

Overall, both of these books of poetry are well worth reading — perhaps side-by-side — not just because of their relevance, together, in Canada today, but because they are engaging and emotionally gripping pieces of storytelling apart.

Clarissa Fortin is rabble’s current books intern.