Change the conversation, support rabble.ca today.

The glaring contrast between employment numbers, and the unemployment rate, was highlighted by last week’s labour force numbers from Statistics Canada (capably dissected elsewhere on this blog by Angella MacEwan).

Paid employment (i.e. employees) declined by 46,000. Total employment (including self-employment) fell by 22,000. Yet the unemployment rate fell to 7 per cent — its lowest level since late 2008.

Fewer people were working, yet the unemployment rate declined. What gives?

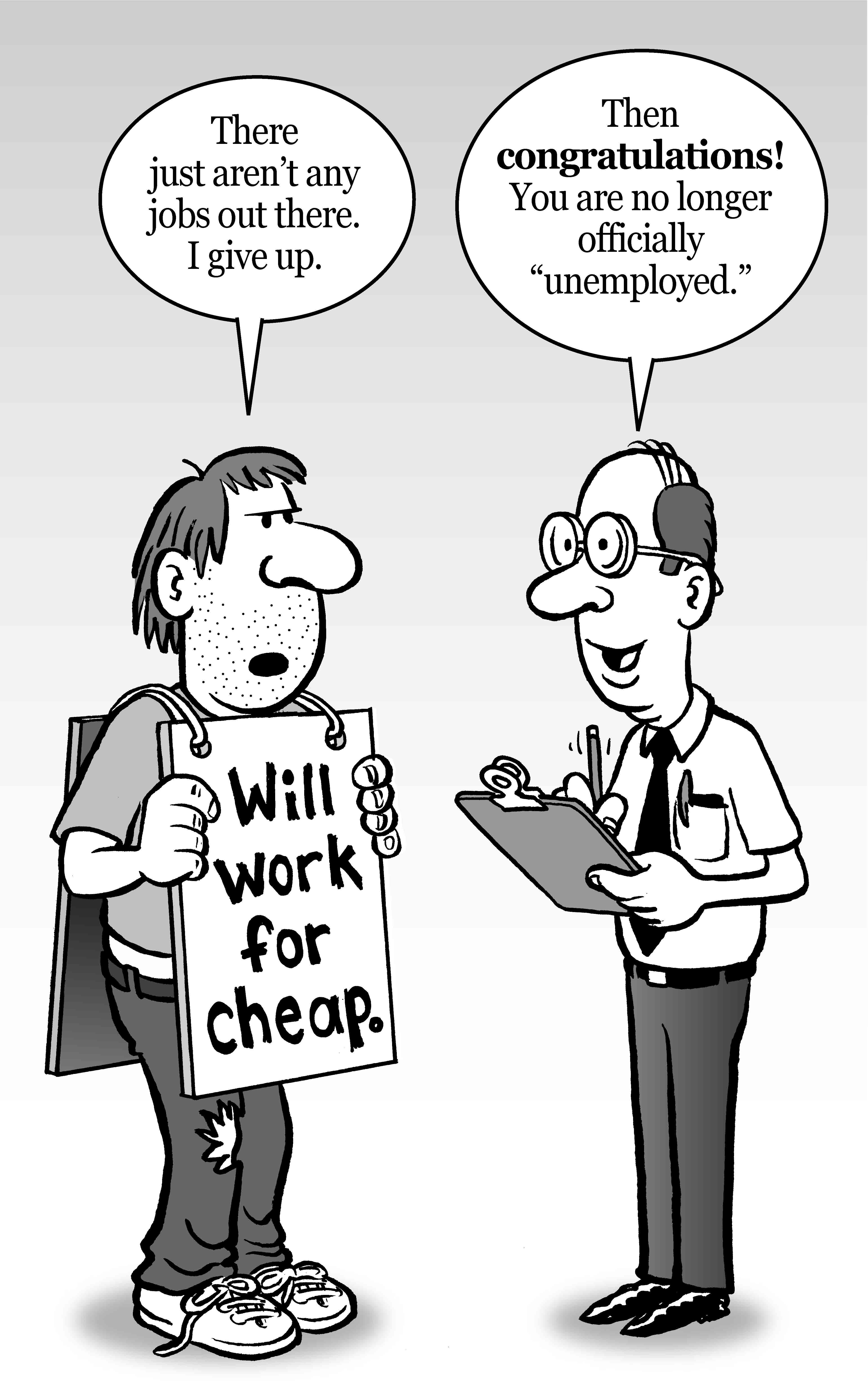

Especially during times of economic weakness, the official unemployment rate is a bad measure of the state of the overall labour market, for familiar reasons: to qualify as officially unemployed, an individual has to be considered to be “participating” in the labour market. If you are not working, participation requires an active job search. A non-employed person who gives up looking, is no longer in the labour market — conveniently disappearing from the official jobless tally.

Einstein defined insanity as doing the same thing over and over again, but expecting a different result. Canadians are not insane: so if they put in 100 resumes with no job offer, they might reconsider putting in the 101st. The supposed disincentives of our EI system can’t be blamed for this, given that most unemployed people don’t get EI benefits at all. In fact, if anything the EI program could conceivably be supporting formal participation, by virtue of the “tough love” job search requirements that the EI police now more stridently enforce.

Ominously, labour force participation is still falling — five straight years now of disengagement by Canadians from the world of work. Overall participation fell to 66.6 per cent (rounded UP, and seasonally adjusted). Compared to peak pre-recession participation, participation has declined almost 2 full points. That decline in participation corresponds to the disappearance of 355,000 Canadian workers — and that discouraged army gets bigger every month.

For a sense of scale, imagine putting 355,000 Canadians to work. At average productivity and wages, they would add $38 billion to Canadian GDP, and close to $15 billion to government revenues.

The employment rate measures the proportion of working age Canadians who actually have a job. It thus steps back from the increasingly arbitrary issue of whether a non-employed person is searching for (non-existent) work with sufficient vigour. It is a better indicator of labour market well-being than the unemployment rate — especially during times of macroeconomic weakness.

The employment rate fell by 0.2 points in January (seasonally adjusted), to 61.9 per cent. That’s the same level it was two years ago. All the jobs created by Canada since the beginning of 2011 have been only sufficient to keep up with population growth — not to offset any of the lasting damage from the recession. The peak pre-recession employment rate was 63.8 per cent. It plunged to 61.3 per cent by the summer of 2009, and then has been “bouncing along the bottom” ever since. Less than one-quarter of that decline in the employment rate during the recession has been recouped by the subsequent halting “recovery.”

Measured (appropriately) by the employment rate, Canada’s labour market is hardly any better than it was during the worst days of the recession. The simple-minded claim by the government that all the jobs lost in the recession have been recouped, and then some, is bankrupt: with Canada’s population growing at close to 1.5 per cent per year, we need to be creating hundreds of thousands of additional jobs, in order to claw back the decline in the employment rate.

The erosion of labour force participation by Canadians is a highly negative development, imposing a wide range of short-run and long-run costs on our economy and society. Focusing on the unemployment rate misses this dangerous story entirely.

The above cartoon, done by Tony Biddle for my book Economics for Everyone, sums up the technical issue perfectly. The most bitter twist of all: the bespectacled nerd from StatsCan has also lost his job, thanks to the Harper government’s cuts to the department!

Jim Stanford is an economist with CAW.