Award-winning filmmaker Min Sook Lee’s Migrant Dreams documentary project has a deep connection to her past — her Korean parents emigrated to Canada in the early 1970s and her father did menial labour, including picking worms, in order to provide for the family.

“I appreciate the struggle,” says Lee. “There was a lot of anxiety because we were poor and new to the country, so I’m very sensitized to issues of migration, acculturation and diaspora.”

Fast-track to 2013 and Lee (whose 2003 NFB film about Mexican farm labourers in Ontario, El Contrato, nabbed a Gemini nomination) is chronicling the hardships of Thai women who pick worms as part of Canada’s Temporary Foreign Worker Program. Her film also includes workers from other countries. The Toronto-based director is well aware of the differences between her father’s position and those of migrant workers today.

“My dad had a pathway to citizenship and security… but now, instead of a citizenship program, we have an expanded temporary worker program denying most of these people access to citizenship.”

The current program allows workers from any country outside Canada to be employed for up to four years — at which point they are required to return to their homeland for four years before being allowed to work under the program again.

While these workers toil in fields, factories and coffee shops, many are denied basic human rights such as access to proper health care, and don’t get raises or vacation pay. Having paid into the CPP and EI programs through their wages, they are unable to reap the benefits as they are either ineligible or find navigating the bureaucracy too daunting to get the money they earned.

“In 2002, we had over 100,000 people under this program, but in 2012, it hit 300,000,” notes Lee.

“The Harper government has taken the concept and exponentially increased the number of guest workers with very little public debate.”

RBC involved in controversy

In fact, a debate did spark up recently after news reports emerged in April that Canada’s biggest bank, Royal Bank of Canada (RBC), was in the process of replacing dozens of its employees in the IT department with temporary foreign workers.

Those temporary workers came from a multinational outsourcing firm from India — iGATE Corp.

“[The program] gives businesses a loophole. They have a profit-driven agenda,” says Lee. “The program is largely unmonitored so it’s open to abuse. It’s designed for systemic exploitation.”

Lee wants Canadians to realize that the temporary worker’s program — as it exists now — should be a concern for everyone, regardless if they work in “3-D” (Dirty, Dangerous, Difficult) jobs or not.

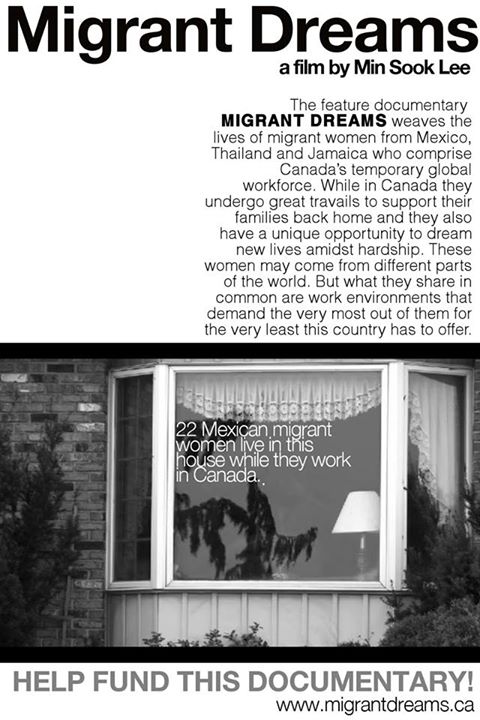

A photo still from the Migrant Dreams documentary.

“It lowers the standards for all workers. There’s no incentive for employers to make jobs more competitive.”

Under the program, businesses apply to the federal government’s program by indicating that they tried but can’t find Canadian workers to fulfill positions. They are then given a special permit — which Lee says is issued “pretty non-discriminately” — to find workers from any country. The program is privatized in that agreements are made between private companies and not between governments.

This is where brokers come in: “They say, ‘Who do you want? Men, women? Jamaicans, Vietnamese, Mexicans?'”

These workers are only allowed to work for one employer and should they leave that employer, many are beholden to the broker for another job.

“As soon as they arrive, the broker picks them up and takes them to a house. He’s their de facto landlord. The broker manages the transportation from the home to the work site.”

Some of these workers — essentially, the world’s poor — have paid as much as $10,000 to a broker and arrive heavily indebted to them while working in Canada.

Indiegogo funding drive

To make the film a reality, Lee has turned to an Indiegogo campaign to raise her own funds. Although she has some network interest (namely TVOntario), with the current funding maze that is documentary today, it’s hard for any filmmaker to get all the money needed.

A moment during filming.

The director has already finished a quick five-day development shoot but she wants to raise about $15,000 in order to keep filming this summer. Lee is following a human rights case involving Thai and Mexican women.

“Their employer put them in housing not fit for humans. The women were sexually assaulted by the owner of the business,” says Lee. “He threatened to cut off their fingers if they signed a petition against him.’

The day I spoke with Lee, she had just found out some of the women were afraid to testify and might not take the stand.

“Fear, intimidation and bullying” are common, according to Lee.

“They’re afraid to speak out.”

Fortunately, the next week, she was told the women are re-considering and may testify.

Circling back to her immigrant roots, the film is Lee’s way of calling to attention to Canada’s immigration policy — pathways which are becoming more restrictive.

“Canada’s criteria are now about money, education and language,” she says. “A specific class of people, who are mostly poor and non-white, are now being streamed in as permanent guest workers. In the past, they might have been immigrants.”

Lee is determined to finish the documentary, whether or not she gets broadcaster backing.

“There is less of a climate of tolerance in Canada compared to 10 years ago,” she observes.

“I see a lot of immigrant-bashing… we are living in culturally conservative times. When you look at Canada’s immigration history — the way Chinese railway workers were treated and the Head Tax, etc. — we should be ashamed.”

“Yet, we are re-living those times again today… I want to live in a Canada that reflects what I believe our country to be: just, equitable and humane.”

June Chua is a Toronto-based journalist who regularly writes about the arts for rabble.ca.