What Is Stephen Harper Reading? That was the title of a book Yann Martel wrote in 2011. He wrote it as a compilation of recommended readings he sent bi-monthly to Prime Minister Stephen Harper. I know it is a bit late but I wish Martel had included among those titles Capital in the Twenty-First Century, the newly released book authored by French economist Thomas Piketty.

As an economist by training, Stephen Harper would be interested in reading what Thomas Piketty has to say about capitalism and the threat that rising inequality is representing for the whole economic system.

But don’t get me wrong; Thomas Piketty isn’t a leftist politician. It just happens that some of what he is preaching corresponds perfectly with what some leftist activists and analysts have been warning us for years, to no avail. Today, the words, analyses and charts inside Piketty’s book are confirming their predictions and giving them credibility — not with neoliberals but with common people who discovered Piketty’s book. The book confirms their suspicions and perfectly describes their realities.

In reality, Piketty’s book came three years late. The Indignados movement in Europe and the Occupy Wall Street movement in the U.S. started way before the book was originally published in French.

However, the difference between Piketty and protest groups is that his work can’t be brushed off as lousy, simplistic or the work of some anarchists. His original contribution, developed together with his colleagues, is a statistical method that allowed him to track the evolution of income and wealth over a long period of time (over the 20th century for America and Britain, and the18th century for France). Thus, he was able to follow inequality through two dimensions: across social classes and through time. He traced the inequality of La Belle Époque (19th century in Europe) and was able to pinpoint the main culprit: the accumulation of wealth and its transmission through inheritance. In today’s words, Piketty was able to track down the 1% that Occupy Wall Street protesters strongly denounced. Indeed, he found out that:

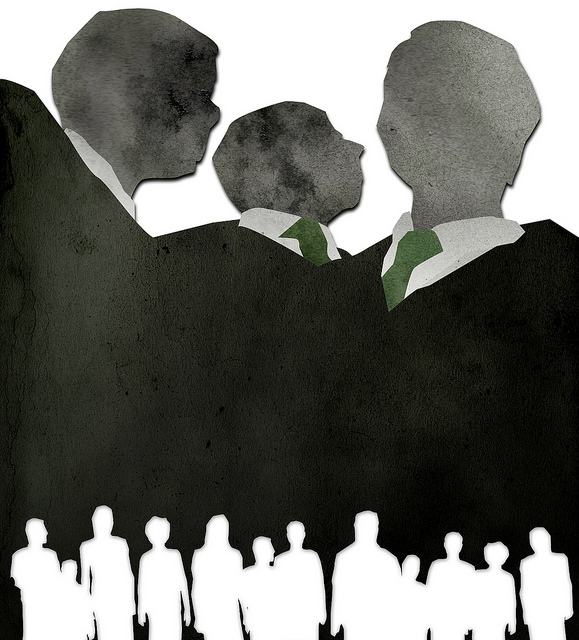

The top 10% owns most (70%) of the capital, and the bottom 50% owns almost none (5%) of it.

Moreover, Piketty drew similarities between rich people of the 19th century and the wealthy today. He even mentioned, unheard of from an economist, some literary characters from the novels of Jane Austen and Honoré de Balzac. In the Belle Époque, the family in which you are born, or to whom you get married, make you poor forever or rich forever.

It is the emergence and later the spread of capitalism that came to change this fatalism. Workers and then middle-class groups, through education and hard work, made a path between the rich and poor and this is how, for instance, the middle class came to represent the most important class in America during the ’50s. Not for a long time, though! The Jane Austen and Honoré Balzac characters of this new world reappeared and concentrated all the wealth in their hands.

It is interesting to note how Piketty emphasizes wealth instead of income as the most important tool for studying inequality — and for this he studied tax records instead of relying, like other economists did in the past, on surveys about salaries and income.

Of course, many critics say that today’s rich made their fortunes through hard work and not through inheritance like was the case in La Belle Époque. It may have been true for some when the American Dream was still a reality but it is no longer the case today. Take the cases of CEOs who keep receiving million of dollars in compensation and yet aren’t good enough to save their firms from financial disasters. And how about JPMorgan Chase, one of the biggest banking and financial multinationals in the world? Didn’t this firm start from a wealthy family?

Piketty advocates for a wealth tax that would reduce the growing inequalities that we currently observe in Canada, in the U.S. and all over the world. Politically, this is extremely difficult if not impossible. In France, Gerard Depardieu and other movie stars or singers went to war against the French government when it tried to increase the taxes on their wealth. In the U.S., Forbes magazine, which promotes wealth through its famous list of the richest people in the world, harshly criticized Piketty’s work.

So after reading Thomas Piketty’s book, can we safely say that America, as the icon of capitalism, is no longer a democracy but an oligarchy? Everyone seems to be afraid to say so!

There are some courageous voices who dare to do so. In their book, The Betrayal of the American Dream, Ronald Barlett and James Steele write: “a sign held by a protester at Occupy Wall Street in the fall of 2011 framed the issue: I don’t mind you being rich. I mind you buying my government.”

Recently, two American political scientists, Martin Gilens of Princeton University and Benjamin Page of Northwestern University, released a report in which they declared:

“…we believe that if policymaking is dominated by powerful business organizations and a small number of affluent Americans, then America’s claims to being a democratic society are seriously threatened.”

Gilens and Page don’t go as far as declaring the U.S. an oligarchy but they nicely frame it as follows: “economic elite domination.” It is exactly what Thomas Piketty discovered through his study of tax records and patterns of inequality.

In Canada, we are not immune to such inequalities and “economic elite domination.” In a recent study by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, it is mentioned that:

“… many gasp at the fact that Canada’s richest 20% of families take almost 50% of all income. But when it comes to wealth, almost 70% of all Canadian wealth belongs to Canada’s wealthiest 20%.”

Piketty’s findings cannot be better confirmed, even here in Canada. Once again, I find myself wishing Stephen Harper would one day read Thomas Piketty’s Capital in the Twenty-First Century.

Monia Mazigh was born and raised in Tunisia and immigrated to Canada in 1991. Mazigh was catapulted onto the public stage in 2002 when her husband, Maher Arar, was deported to Syria where he was tortured and held without charge for over a year. She campaigned tirelessly for his release. Mazigh holds a PhD in finance from McGill University. In 2008, she published a memoir, Hope and Despair, about her pursuit of justice, and in 2011, a novel in French, Miroirs et mirages.

Image: Jared Rodriguez / Truthout