In February 2012, the scientific journal Nature published an editorial opinion piece, Frozen Out, calling on the Canadian government to reform policies that restrict media access to federal scientists. This followed numerous stories documenting delays and confusion in how different federal departments respond to requests for media interviews on scientific matters.

How has the Harper government reacted? A new report, Can Scientists Speak, finds that federal media policies remain far more restrictive than those in the United States, and gives low to failing grades to nearly all 16 departments that employ scientists.

According to the report, “When compared to communication policies in the U.S. … Canadian policies lag far behind in their ability to facilitate open and timely communication between journalists and federal scientists, to incorporate measures that safeguard against political interference, and to protect scientists’ right to free speech.”

The report found startlingly wide differences in policies across departments. For example, while Health Canada received full marks for timeliness (its policy is to acknowledge media inquiries “within one hour”), it scored only 3/25 on “safeguards against political interference.” Surely, given ever-present threats of new disease outbreaks (for example, the Ebola virus) and other health risks, federal health scientists should be allowed to speak openly to the media without having their messages massaged by departmental communications officials.

One recommendation in the new report is that federal scientists be allowed to “express personal opinions in a professional and respectful manner as long as they make clear they are not representing the views of their department.” This is standard practice in most countries, including the U.S. But only the Department of National Defence explicitly permits this in Canada. National Defence is also the only science department that posts its science communication policies on a public website and does not require scientists to get pre-approval before connecting with media.

What might be the Harper government’s motivation for placing unusually severe restrictions on scientists’ contact with the media? The report discusses possible fears that scientists may openly criticize government policies. But federal scientists, like all civil servants, are subject to a provision in the government-wide Values and Ethics Code, making them responsible for “loyally carrying out the lawful decisions of their leaders and supporting ministers in their accountability to Parliament and Canadians.” At the same time, the Code acknowledges a need for balance between this “duty of loyalty” and employees’ right to freedom of speech.

Given the sensitivity of the Harper government to media comments on its pro-oil and gas development agenda, it is perhaps unsurprising that Natural Resources Canada’s science communication policies received the lowest failing grade (“F”) in the report.

The authors of the report note that departmental policies may not be reflected in actual practice. They gave Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) policies a “C” — high relative to other departments — but also note that DFO scientists “are the least satisfied with the way the federal government or DFO communicates or broadcasts the results of their work to the media or general public.”

The federal clampdown on science goes well beyond media communications. Chris Turner, in his book The War on Science, says that Canada has entered an “age of willful blindness,” in which “the whole underlying foundation of government and the acceptable uses of the political sphere are now in flux.”

Turner attributes this blindness to “the Harper agenda’s abiding mistrust of expertise and its contempt for any kind of science not being applied directly to an economic activity of immediate benefit to Canadian industry and self-evident appeal to Conservative voters.” He cites a March 2012 speech in which the Minister of State for Science and Technology, Gary Goodyear, described his vision for the National Research Council as a “concierge” for industry. The dictionary definition of “concierge” is “an employee whose job is to assist guests” — a telling characterization of the relationship between the Harper government and big business.

Canadian business demands are flowing freely into the Harper government. But what flows back to the public is basically propaganda — carefully crafted messages designed for maximum voter appeal, with little regard for factual content or scientific accuracy.

Ole Hendrickson is a forest ecologist and current president of the Ottawa River Institute, a non-profit charitable organization based in the Ottawa Valley.

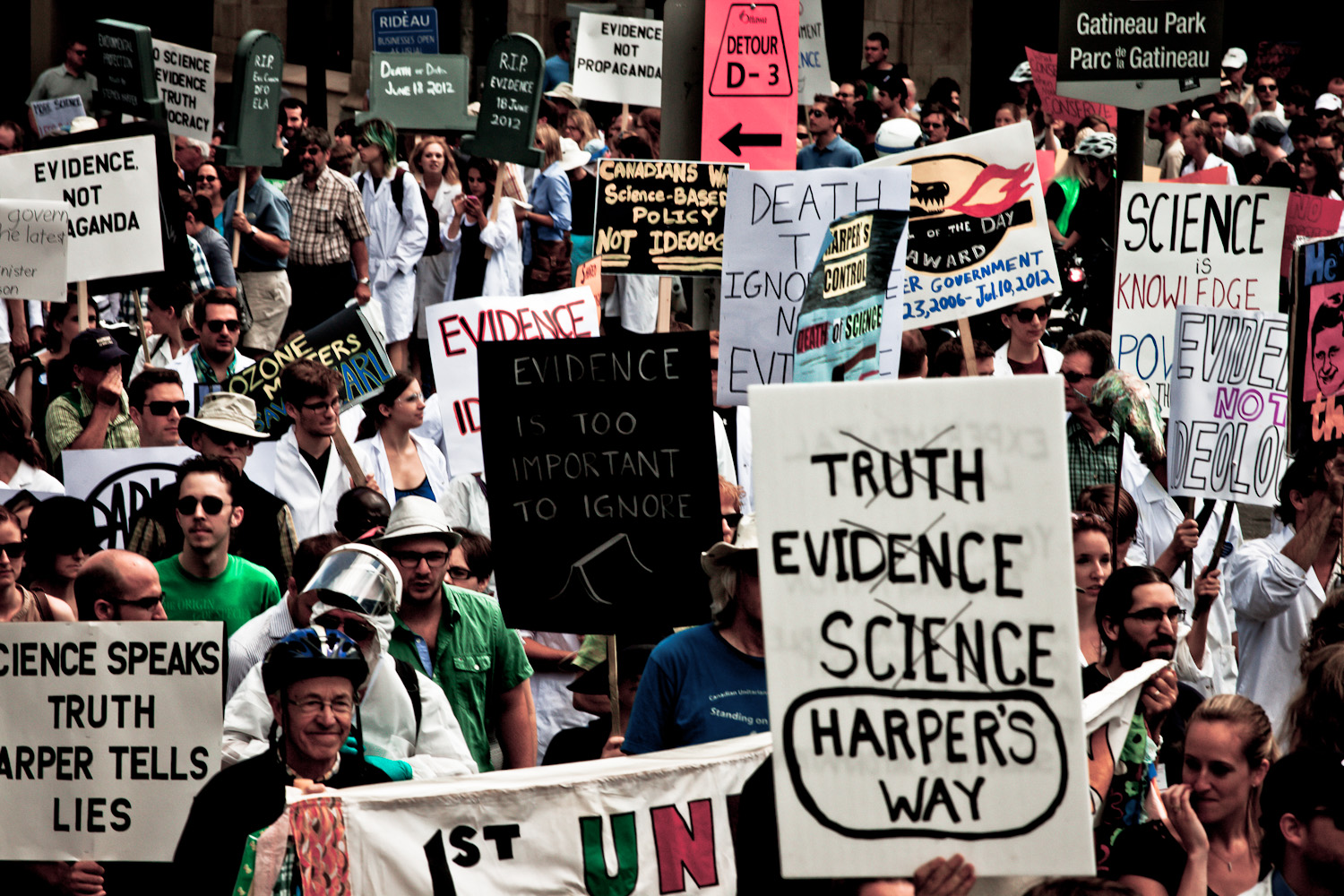

Photo: Richard Webster/deathofevidence.ca