UXBRIDGE, Canada (IPS) – This December, 195 nations plus the European Union will meet in Lima for two weeks for the crucial UN Conference of the Parties on Climate Change, known as COP 20. The hope in Lima is to produce the first complete draft of a new global climate agreement.

However, this is like writing a book with 195 authors. After five years of negotiations, there is only an outline of the agreement and a couple of “chapters” in rough draft.

The deadline is looming: the new climate agreement to keep climate change to less than two degrees Celsius is to be signed in Paris in December 2015.

“A tremendous amount of work has to be done in Lima,” said Erika Rosenthal, an attorney at Earthjustice, an environmental law organisation and advisor to the chair of the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS).

“Time is short after Lima and Paris cannot fail,” said Rosenthal. “Paris is the key political moment when the world can decisively move to reap all the benefits of a clean, carbon-free economy.”

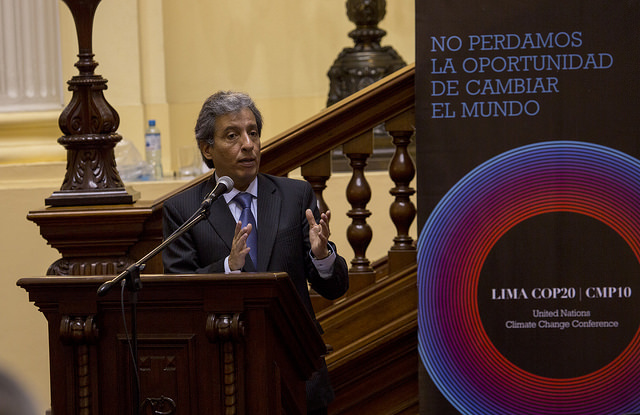

Success in Lima will depend in part on Peru’s Environment Minister Manuel Pulgar-Vidal. As official president of COP 20, Pulgar-Vidal’s determination and energy will be crucial, most observers believe.

Climate change is a major issue in Peru, since Lima and many other parts of the country are dependent on freshwater from the Andes glaciers. Studies show they have lost 30 to 50 per cent of their ice in 30 years and many will soon be gone.

Pulgar-Vidal has said he expects Lima to deliver a draft agreement, although it may not include all the chapters. The full draft with all the chapters needs to be completed by May 2015 to have time for final negotiations.

The future climate agreement, which could easily be book-length, will have three main sections or pillars: mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage. The mitigation or emissions reduction pillar is divided into pre-2020 emission reductions and post-2020 sections.

Peru’s environment minister, Manuel Pulgar-Vidal, during one of the many events held to promote the COP 20. As chairman of the conference, his negotiating ability and energy will be crucial to the progress made towards a new draft climate agreement. Credit: COP20 Peru

Both remain contentious, in terms of how much each country should reduce and by when.

Climate science is clear that global CO2 emissions must begin to decline before 2020 — otherwise, preventing a 2C temperature rise will be extremely costly and challenging.

However, emissions in 2014 are expected to be the highest ever at 40 billion tonnes, compared to 32 billion in 2010. This year is also expected to be the warmest on record.

In 2009, at COP 15 in Copenhagen, Denmark, developed countries agreed to make pre-2020 emission reductions under the Copenhagen Accord. However, those commitments fall far short of what’s needed and no country has since increased their “ambition,” as it is called.

Some — like Japan, Australia and Canada — have even backed away from their commitments.

UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon held a special summit with 125 heads of state on Sep. 24 in hopes countries’ would use the event to announce greater reductions. Instead, developed countries like the U.S. made general promises to do more while hundreds of thousands of people around the world marched to demand their leaders to take action.

The ambition deadlock was evident at the UN Bonn Climate Conference in October with developing nations pushing their developed counterparts for greater pre-2020 cuts.

However, the country bloc known as the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) proposed a supplementary approach to reducing emissions that involves countries sharing their knowledge, technology and policy mechanisms.

Practical, useful and necessary, this may become a formal part of a new agreement, Rosenthal hopes.

“There were very good discussions around renewable energy and policies to reduce emissions in Bonn,” agrees Enrique Maurtua Konstantinidis, international policy adviser at CAN-Latin America, a network of NGOs.

“Developed countries need to make new reduction pledges in Lima,” Konstantinidis told TA.

This includes pledges for post-2020 cuts. Europe’s target of at least 40 per cent cuts by 2030 is not large enough. Emerging countries like China, Brazil, India and others must also make major cuts since the long-term goal should be a global phase-out of fossil fuel use by 2050 to keep temperatures below 1.5C, he said.

This lower target is what many African and small island countries say is necessary for their long-term survival. The mitigation pillar still needs agreement on how to measure and verify each country’s emission reductions. It will also need a mechanism to prevent countries from failing to meet their targets, Konstantinidis said.

Ironically, the most advanced mitigation chapter, REDD (Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation), is the most controversial outside of the COP process.

REDD is intended to provide compensation to countries for not exploiting their forests. Companies and countries failing to reduce emissions would pay this compensation.

The Peruvian government wants this finalized in Lima but many civil society and indigenous groups oppose it. Large protest marches against REDD and the idea of putting a price on nature are very likely in Lima, Konstantinidis said.

“Political actors appear totally disconnected from real solutions to tackle global warming,” said Nnimmo Bassey of the No Redd in Africa Network and former head of Friends of the Earth International.

REDD is a “financial conspiracy between rich nations and corporations” happy to trade cash for doing little to reduce their carbon emissions, Bassey said in an interview.

The only way to stop this “false solution” is for a broad alliance of social movements who take to the streets of Lima, he said.

The adaptation pillar is mainly about finance and technology transfer to help poorer countries adapt to the impacts of climate change. A special Green Climate Fund was set up this year to channel money but is not yet operational.

At COP 15, rich countries said they would provide funding that would reach 100 billion dollars a year by 2020 in exchange for lower emissions reductions. Contributions in 2013 were only 110 million dollars.

Promises made by Germany and Sweden in 2014 amount to nearly two billion dollars, however, payments will be made over a number of years. It is also not clear how much will be new money rather than previously allocated foreign assistance funding.

“Countries need to make new financial commitments in Lima. This includes emerging economies like China and Brazil,” said Konstantinidis.

Loss and damage is the third pillar. It was only agreed to in the dying hours of COP 19 last year in Warsaw, Poland. This pillar is intended to help poor countries cope with current and future economic and non-economic losses resulting from the impacts of climate change.

This pillar is the least developed and will not be completed until after the Paris deadline.

This story was originally published by Latin American newspapers that are part of the Tierramérica network. It was also published on IPS, and edited by Kitty Stapp.

Stephen Leahy is the senior science and environment correspondent at Inter Press Service News Agency (IPS) based in Rome and Montevideo. To continue this work at a time of severe cutbacks and closure of many media, Leahy launched Community Supported Journalism.

Edited by Kitty Stapp