Today’s labour force numbers are ugly, there’s no other word for it. Employment down 29,000 jobs. Paid employment (i.e. not counting self-employment) down 46,000 jobs. The only reason the unemployment rate held steady (at 6.9 per cent) is because labour force participation fell again: by almost two tenths of a point, to just over 66 per cent. That’s the lowest level of labour force participation since 2001. Convenient for suppressing the headline unemployment rate, but socially destructive and very costly in the long run (as more and more Canadians lose contact with the labour market).

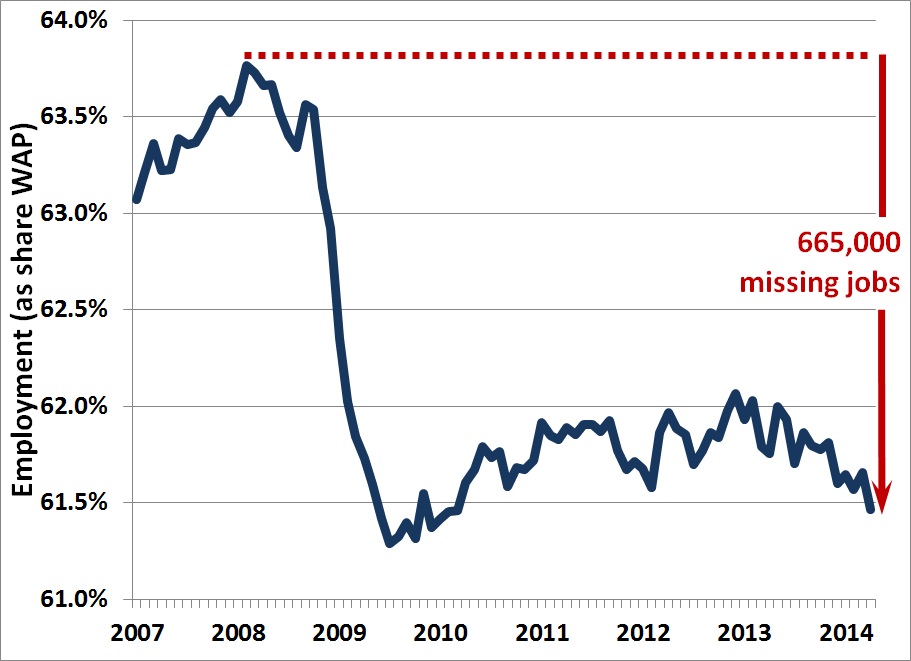

In a weak macroeconomy, the employment rate is a better indicator of labour market strength, since it avoids the arbitrary distinction regarding whether someone is sufficiently “active” in their job search to qualify as being officially “in” the labour market. The employment rate also fell 0.2 points in April, to under 61.5 per cent. That’s the lowest employment rate recorded since March 2010 (as the economy was starting to claw its way back from the worst of the recession). In fact, today’s employment rate is hardly any higher than the low point reached in July 2009 (61.3 per cent), when the recession officially ended (ha!) and real GDP began to grow again. The employment rate has been declining fairly steadily since late 2012, and has slipped over half of a point in that time.

The figure above illustrates the sharp fall of the employment rate during the recession, the initial partial recovery during 2010 (when government had its foot on the stimulus gas pedal), but then the reversal of that partial progress in subsequent years (as government switched from gas to brake, and austerity became the dominant theme of fiscal policy). Less than a tenth of the damage done to the employment rate in the recession, has been repaired. This exposes the federal government’s claim that Canada’s labour market has recovered from the recession as desperate spin-doctoring. Since more Canadians are working today than before the recession, they claim, they’ve handled things well. They must believe we all fell off the turnip truck yesterday — because we couldn’t possibly figure out that since the working age population grew by 2 million in that time, we might need just a few more jobs than we had in September 2008 in order to achieve the same supply-demand balance. To restore the employment rate back to its pre-recession peak would require an additional 665,000 jobs in Canada. That’s the true unrepaired damage remaining from the recession.

The erosion of Canada’s labour market performance over the last couple of years is not surprising in light of the general stagnation of the main drivers of economic growth in our system. The main potential engines of output, income, and employment are: business non-residential investment, exports, government spending (on consumption and investment), housing construction (residential investment), and consumer spending. The first four are the autonomous (or leading) sources of demand. The last one, consumer spending, normally tends to follow incomes in the long run — although it can strike out on its own when unusual borrowing allows consumers to spend more than they make. Rising consumer debt (despite lots of hand-wringing by finance ministers and central bank governors) is still allowing this to happen. Consumer spending has been the most consistent source of new spending power in Canada since the recession. But how long can it last, without new jobs and rising incomes for working people?

The second figure shows the contribution to GDP growth made by the major components of demand in the year ending in the 4th quarter of 2013. It illustrates starkly that Canada’s economy has no engine. Housing, business investment, and government all declined slightly in the year (the last reflecting austerity policies at all levels of government). The trade sector improved slightly in 2013 — though is still mired deeply in deficit (with a $60-billion current account deficit, 4 times bigger than the federal government deficit). Indeed, the trade deficit has deteriorated again in the last couple of months. Consumers, so long as they are prepared to keep borrowing and spending like drunken sailors, are the only thing saving our bacon. The other big source of GDP growth through 2013 was inventory accumulation. Yikes! That’s not something you want to build a recovery on: rather, it’s a sign that sales are already weaker than expected, meaning future cutbacks in production are likely.

The private sector isn’t leading growth in Canada (neither through investment nor exports). In the absence of private sector leadership, government must lead the way with more investment and spending, not less. But the ideology of austerity is doing the opposite. No wonder Canada’s labour market is slipping back into a recession-like funk (and the official unemployment rate doesn’t tell the whole story of that funk).

A couple of other tidbits from today’s report: Ontario created 18,000 jobs in April (26,000 full-time jobs, offset a bit by a loss of part-time jobs). That’s way more than any other province. Not convenient for the strange interventions by Harper government officials in the current Ontario election campaign (with federal cabinet ministers and other spokespeople jumping into the fray in support of Tim Hudak’s talking points).

Second, this month’s Daily featured a new sub-section comparing Canadian and U.S. unemployment rates, using a consistent (ie. U.S.-style) methodology for measuring active job search. The Americans had another good month in April, and their unemployment rate is now down to 6.3 per cent. Someone in Statistics Canada (perhaps with some helpful advice from the PMO??) probably felt sensitive about the widening and unfavourable unemployment rate gap between the two countries — and hence took it upon themselves to explain that if you use consistent statistical definitions, Canada is still slightly better than the U.S. (our unemployment rate would be 6.0 per cent using U.S. definitions). That’s legitimate from a statistical perspective, but won’t change the perception that Canada’s relative performance is slipping badly.

The government’s claim to have weathered the recession better than anyone else on the planet was never remotely true. But it’s getting less and less true by the month.

Jim Stanford is an economist with Unifor.