Like our labour coverage? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Just three weeks before the federal election comes a report from Morgan Stanley that should remind everyone that the election is still about the economy. The message of the paper is as unambiguous as it is surprising: the era of cheap labour is over. It all has to do with demographics, which are changing, and public policy, which is not.

I have written more than once over the years about the devastating impact of so-called “labour flexibility” policies — devastating to employees, families, productivity, equality, communities, the birth rate (yes, the birth rate) and the economy as a whole. What is stunning to me is that almost no one in the Canadian media, and few in the labour movement, seems to have a clue about its importance.

For all the talk about what will grow the economy — and the leaders’ debate on the topic was worse than useless; it was embarrassing — the key component to future economic growth is rising wages and salaries. We are programmed to dismiss such claims as “far left” nonsense but that handy epithet doesn’t work when the observation is made by the likes of co-author Charles Goodhart, a former member of the Bank of England’s rate-setting committee.

Goodhart argues that a dramatic decline in the size of the labour force, caused by “the greying population may reverse three long-term trends: a decline in real (inflation-adjusted) interest rates, a squeeze on real wages and widening inequality.”

Decreasing labour power

The percentage of the global population who were working experienced a huge increase in recent decades due to the post-war baby boom in developed countries and the entry of China and Eastern Europe into the capitalist system. That abundance of working-age people created the conditions for the cheapening of labour and the reduction of its bargaining power. That, says Goodhart is already ending, noting that “population growth in the rich world, which was 1 per cent a year in the 1950s, has fallen to 0.5 per cent and should drop to zero by 2040.”

Governments eager to advance the interests of large corporations took advantage of this labour surplus by developing convenient theories to justify a broad assault on wages and salaries — and unions. Things like labour standards, generous employment insurance and poverty-reducing welfare schemes made labour “inflexible,” the argument went — by which they meant uppity workers demanding their fair share.

It was Liberal finance minister Paul Martin who implemented the grand plan in the mid-1990s. Insisting that inflation greater than two per cent was a threat to the economy, Martin used high interest rates to actually suppress economic growth and deliberately create high levels of unemployment. Few people recall that under Martin’s reign, unemployment hovered around nine per cent for most of the 1990s — higher than at any time following the 2007-08 financial collapse.

Artificially high unemployment was perhaps the most powerful weapon, but Martin also hit workers with draconian cuts to EI eligibility and the elimination of the Canada Assistance Plan (CAP). The CAP transferred money to the provinces and was targeted specifically at establishing a minimum national standard for welfare. With its cancellation, the provinces were free to radically reduce social assistance rates. The provinces also began cutting back on the enforcement of labour standards — dealing with things like time-and-a-half for overtime, disallowing back-to-back shifts, unpaid apprenticeships, notice of dismissal, sexual harassment, etc. Added up, it meant a dramatic reduction in the power of labour to bargain with employers.

Of course part of the “flexibility” agenda was directed at unions and with more and more part-time and temporary positions in low-wage, high turnover jobs, organizing became increasingly difficult. One experiment in well-funded anti-unionism was called Canadians Against Forced Unionism (CAFU). It was a creature of the National Citizens Coalition, the right-wing lobby group headed by Stephen Harper in the late 1990s. The president of CAFU was none other than Rob Anders, the extremely right-wing Calgary MP who managed to retain Harper’s loyalty through multiple controversies.

The effects of the attack on workers’ incomes and rights, on productivity, and on private investment, mirror exactly the results that the Morgan Stanley report details. Canadian employers, ever eager to take the easy road to profits, reflected the broad trend. Goodhart writes: “Easy hire and fire is at the cost of organizational learning, knowledge accumulation and knowledge-sharing, thus damaging innovation and labour productivity growth.” Canadian productivity growth has been moribund for 20 years, largely as a result of corporate reliance on low wages, facilitated by Liberal and Conservative governments.

Rise of the precariat

The 25-year pursuit of cheap labour across the developed world has resulted in what has been called the “precariat” — those working in precarious, low-paying jobs with little or no protection from ruthless employers. Paul Martin’s anti-labour crusade (continued by Stephen Harper) has given Canada the dubious honour of having the third-highest percentage of low-paying jobs in any of the 35-nation OECD countries — with 22 per cent, it is third behind the U.S. and Ireland (the average is 16 percent).

What effect would rising salaries and wages have on private investment? It’s a critical question for Canada given that large corporations are currently sitting on over $600 billion in idle cash. The Morgan Stanley report states: “As for investment by firms, rising wages will encourage companies to substitute capital for labour. Corporate investment could rise.”

The relentless squeeze on workers’ pay (the net real increase in average Canadian income between 1980 and 2005 was $52) and deteriorating working conditions are at the root of the looming labour shortage. According to the 2012 National Study on Balancing Work and Caregiving in Canada: “Employees who are already overloaded…are less likely to add to that overload by having children (i.e., more likely to say that they have decided to have fewer children/no children).” As if to underline the issue, Statistics Canada just reported that for the first time ever, people aged 65 and over in Canada outnumber those 14 and under.

The creation of the precariat was rooted in the untested assumption that a strong safety net (EI, social assistance, labour standards) added up to a “disincentive” for workers to work hard. It turns out that the precariat has demonstrated in response that if you treat people like crap they don’t actually work harder — they work less. A Delft University study concluded:

“A flexible workforce needs an expanded management bureaucracy to oversee it. Because precarity damages trust, loyalty and commitment…it demands more management and control. An entire generation of free-market workers has begun to act according to the factory adage of the old Soviet Union: ‘We pretend to work, they pretend to pay us.'”

The Morgan Stanley paper contains a warning to employers — that if they continue to mistreat and underpay their employees they will pay the price with an increased militancy as labour shortages kick in and workers’ bargaining power increases. Goodhart recommends that employers get out ahead of the curve: “The synergies are stark: if the global economy needs a return to higher-paid work, then attacking precarity is the quickest way of achieving that.” I can’t see that happening any time soon and personally I’d like to see a little militancy for a change.

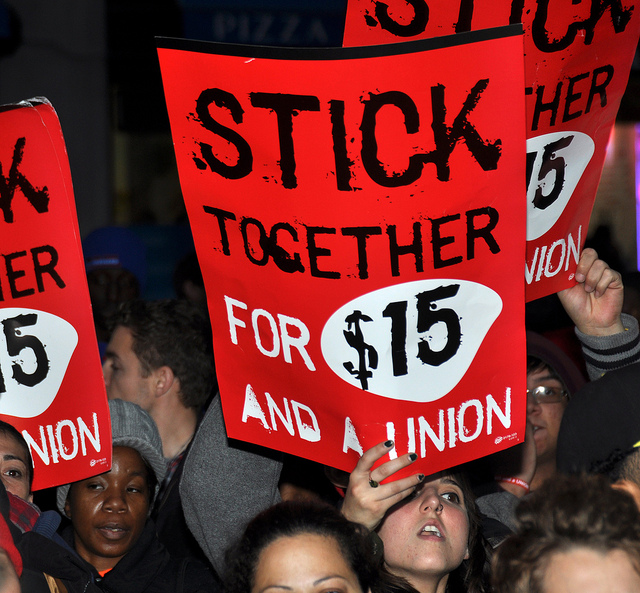

But surely there are politicians and labour leaders out there who in the interim can fight to make life better for workers and actually grow the economy at the same time. The NDP has dipped its toe in these waters with its $15-minimum-wage promise and child-care pledge. But we need much more: a movement, led by unions, for a return to strongly enforced (and enhanced) labour standards, a robust EI program where (once again) 70 per cent qualify for benefits, the elimination of the Temporary Foreign Workers Program, social assistance that lifts people well past the poverty line (or perhaps a Guaranteed Annual Income) and, for good measure, the public shaming of employers who abuse their workers.

Murray Dobbin has been a journalist, broadcaster, author and social activist for 40 years. He writes rabble’s State of the Nation column, which is also found at The Tyee.

Photo: Michael Fleshman/flickr

Like our labour coverage? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.