Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.

Hildegard De Vuyst recalls the first time a hybrid dance performance based on a traditional Palestinian/Arab dance called dabke was performed back in 2009. It occurred after a four-week workshop with 11 Palestinian performers.

“We did it outdoors in the town of Birzeit and near the mosque. It was lovely,” the Brussels-based choreographer/dramaturge recalls. “And from that workshop, we have performed and altered it over the years.”

Called In the Park, that workshop and performance would become the seeds for Badke, which has its Canadian premiere in Toronto from Feb. 17 to 20 at the Fleck Dance Theatre. The production is a collaboration between KVS (the Brussels City Theatre), Les Ballets C de la B, and the A.M. Qattan Foundation.

“I heard Toronto is such an exciting city with people from all over the world,” De Vuyst says. “We are looking forward to seeing a very diverse audience.”

In the Park cemented De Vuyst’s collaboration with Badke’s co-choreographers, Koen Augustijnen and Rosalba Torres Guerrero. It also helped the trio create a blueprint for the performance as a multidisciplinary dance utilizing dancers of diverse backgrounds in movement.

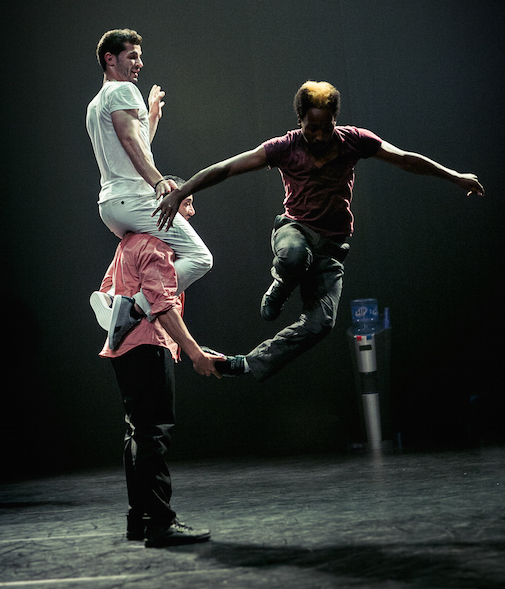

Over the years, De Vuyst has worked with different Palestinian performers which allows the choreographers to also infuse the backgrounds of the various dancers into the work: from circus arts to the Brazilian martial arts dance capoeira.

This time, the production gathers six Palestinian women who live in Israel with six Palestinian male hip-hop dancers from Nablus.

“The show has such a long history now, we completely re-made it in 2015 with a new team.”

Social folk dance

Badke’s foundations lie in dabke, an Arabic social folk dance. It is the only kind of physical expression permitted in public, according to De Vuyst.

“It’s the idea of a collective, a group, ” she explains. “It’s a line dance, shoulder to shoulder, and it’s very connected to the floor. If you’ve ever seen Russian Cossack dancing, it’s similar.”

Transforming the dance meant also playing with its rules. The music itself is the kind of popular music you would hear on buses in Palestine — “flashy Arabic music,” as De Vuyst puts it.

As for the physical aspects of the dance, that has also been played with.

“It’s about everything from the thighs to the feet and from the chest to the hands. So, no hips, pelvis or ass.”

De Vuyst, Augustijnen and Torres Guerrero decided to include the parts of the body that are traditionally ignored or, as De Vuyst puts it: “We called it The Ass Dance section.”

As far as selecting dancers, she points out that it was crucial in every production to include people who were not conventional dancers or had a dance education.

“We call it a bastard dance where one dancer can teach another something different. It transforms the material and regenerates and evolves.”

Badke is described as “politically charged” and about the survival of the Palestinian people. Asked about how this is expressed on stage, De Vuyst provides a couple of details.

“It’s very physical and leads to exhaustion. The dancers are neat and clean at first and then their costumes start to show sweat, the ties go off,” she says. “But they keep going. They don’t give in and at certain times the electricity is cut and the dancers start to sing and continue to dance.”

Badke translates across boundaries she says. When it was performed in Kinshasa, the audience was very receptive and understood the performance at an emotional level.

“They could connect to it strongly because they also experience cuts to electricity and they’ve been through a lot too,” De Vuyst points out. “When there is no electricity, you still have the means to create your own existence.”

De Vuyst feels audiences are craving a bodily emotional connection to dance and that’s why the creators of Badke eschewed what would be seen as typical depictions of life in Palestine.

“We didn’t want to show violence or war. We wanted to show resilience and lust for life,” she emphasizes. “They suffer but they continue to dance because to stop would mean defeat and they cannot let that happen.”

Fleck Dance Theatre at Queen’s Quay West, Toronto

June Chua is a Berlin-based journalist who regularly writes about the arts for rabble.ca.

Photos by Danny Willems.

Like this article? rabble is reader-supported journalism. Chip in to keep stories like these coming.