I went to Sir John A. Macdonald Junior High in Calgary and grew up at a time when Canadian history was taught from a certain point of view: he is the founding father of the country, he united Upper and Lower Canada, and the nation was forged.

And now, the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario (ETFO) has pushed forward a motion that has triggered deep national hand-wringing. It urges school boards across the province to strip the name of the father of Confederation from public schools and buildings, putting a harsh light on what kind of history we learn.

“We need to look at different histories because they are a powerful form of remembering and this project is about imagining new ways of living that are more equal and just,” Julia Smith of the Graphic History Collective tells rabble.ca in an interview.

The proponents of the motion say Sir John A. Macdonald was the architect of genocide because he created the residential school system, which lasted in Canada until 1996 — and resulted in the death, abuse and continuing cycles of abuse among Indigenous peoples, as witnessed by our Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

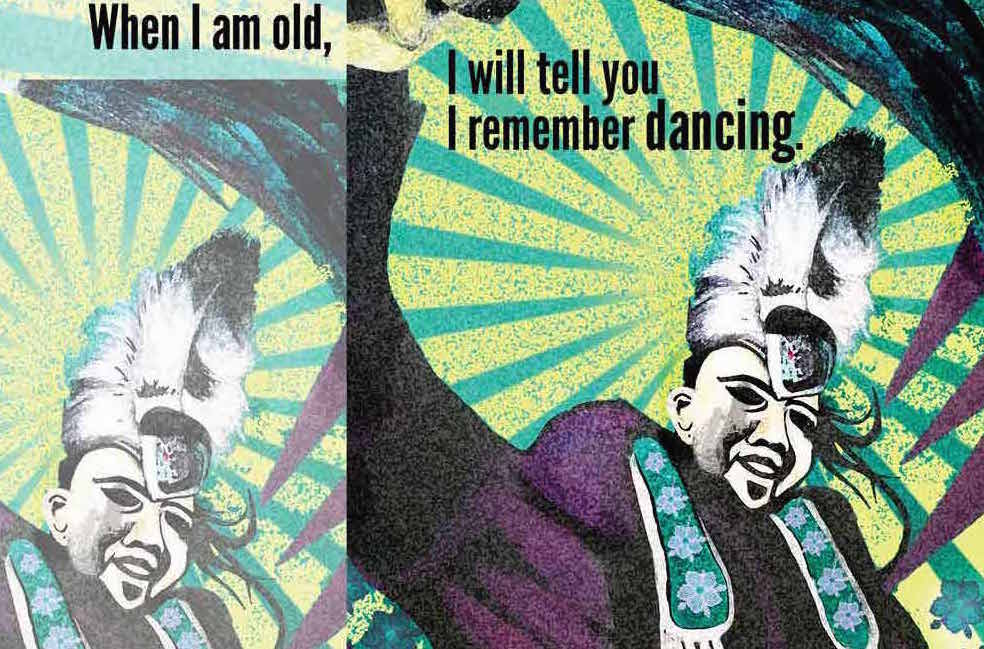

Smith’s collective of artists, activists, writers and researchers, based primarily in Western Canada, seeks to examine Canadian issues and to retell them in a more realistic manner. This year, the collective has embarked on an ongoing poster project: Remember | Resist | Redraw: A Radical History Poster Project.

They decided to pick 2017 as it marked the 150th birthday of Canada as a country.

“It’s not that we shouldn’t celebrate Canada’s 150th but that there is a need for a space to explore these social issues,” said Smith. “We decided that a downloadable poster online was the best way to disseminate this kind of project versus a graphic novel, which we have done in the past.”

The collective grew from an initial project back in 2008 which re-examined Canada’s labour history and resulted in May Day: A Graphic History of Protest.

“Since then the collective has had a lot of writers and artists inquire about how they can get involved so we have continued to do other projects,” said Smith. GHC is nonprofit and relies on donations to cover basic costs such as maintaining its website and designing its comic books.

“With the poster project, we didn’t realize how much interest it would generate; we initially envisioned it as year-long but now, as artists approach us with different topics, we’re going to keep it going.”

The posters tackle diverse topics from the evolution of caregiving work by racialized women in Canada (many of them Filipina) to Indigenous land rights to Sir John A. Macdonald.

“It’s hard for people to see a better world if they don’t see their history in it, so this is a way of highlighting stories that are often marginalized in dominant narratives of Canadian history.”

Smith, who is a postdoctoral fellow studying the history of union organizing, said she’s “excited” by the prospect of turning historical research into something more creative that can connect with the public.

“It’s challenged me as an historian because we work with words and now I see that we can open up our research, using this other tool, to share what we know.”

The poster project has been collaborative. GHC doesn’t impose topics on its artists and writers — instead individuals come to them with ideas.

“We decided to create a space for others to tell their stories and it’s nice we are getting a range of topics.”

One poster highlights the political nature of Pride — with one enthusiastic Canadian posting a picture of the poster up in Toronto’s Kensington Market during Pride Week this past June — and another looks at Métis resistance.

“There is an appetite in this country for this kind of conversation — we are seeing a lot of positive reaction so far,” Smith noted. “We’ve been told people are printing them up for use in their elementary classrooms and university classrooms and talking about them.”

While the project is nonprofit, GHC also advocates for artists’ fees if the works are reproduced, for example in mainstream media such as a magazine or newspaper. Smith says media organizations have ponied up and paid artists.

When asked about the inspiration for the collective’s work, she points to a quote that is on their website and the first poster in the project by queer Canadian activist and sociologist Gary Kinsman:

“[T]o develop our radical imagination, we need to work against the systemic social organization of forgetting, and a necessary antidote to the social organization of forgetting is the resistance of remembering.”

June Chua is a Berlin-based journalist who regularly writes about the arts for rabble.ca.

Poster images courtesy of the Graphic History Collective.

Portion of poster “Twelve Thousand Moons” — Image by Angela Sterritt, Words by Erica Violet Lee.

Portion of John A. Macdonald poster — Poster by Sean Carleton