At 8:45 a.m. on September 24, 1986, Toronto police knocked on the window of Dr. Nikki Colodny’s vehicle and placed her under arrest. Taking just a moment to pack her knitting and her Holly Near cassette tape, Dr. Colodny went quietly to the courthouse where she was charged, alongside her colleagues Dr. Henry Morgentaler and Dr. Robert Scott, for conspiracy to commit a miscarriage.

Originally trained as a psychotherapist and family physician, Colodny joined the Ontario Coalition for Abortion Clinics (OCAC) as an “envelope licker” in the early 1980s, and eventually trained as an abortion provider at Henry Morgentaler’s clinic in Montreal. From 1986 until the landmark Supreme Court decision R v Morgentaler in January 1988, Colodny provided abortions in contravention of Canadian law.

This past winter, Colodny returned to Canada to record two oral history interviews for the University of Ottawa Women’s Archives, and kindly agreed to speak with my third-year Cultural Studies class at Carleton University. In addition to detailing Colodny’s pathway to civil disobedience, these recordings show how far we have come in the 36 years since abortion was decriminalized. I was especially grateful for Colodny’s frank discussion with my students, most of whom were born after 1988 (including myself) and have never experienced criminal restrictions on reproductive health care.

Colodny experienced some trepidation about becoming an abortion provider when the OCAC’s Judy Rebick asked her to do so over dinner in the mid-1980s: “She really thought I should think about it,” Colodny explained, “She told me that it would help build the movement to have a feminist be a provider.”

“I do think that if I knew then [how bad the harassment would get] in those years, that I may not have done it… It’s like, you take a step, and you don’t know what it’ll bring. This undertaking was like that. There was no way to know the level of violence, the doctors being shot and killed, the arson, the in-your-face-people all the time.” Matter-of-factly, however, she concluded that “If I have the skills, and it’s needed, then I should do this. And that’s what I did.”

Colodny had grown up in the United States during the politically tumultuous years of Civil Rights, Black Power, and the U.S. war in Vietnam. “The foment was all around us,” she recalled, “there were demonstrations against the war, I was very much against the war. There were Civil Rights activities, registering voters. I didn’t participate in a lot of that, I was much more counterculture, like, hippie… But I was in solidarity with them.”

Colodny attended Antioch College in 1965, where she “sat around listening to political discussions and missing classes” before eventually dropping out. When her then-boyfriend became eligible for the draft, the couple fled to Canada alongside thousands of other “draft dodgers” who refused state-mandated military service and deployment to Vietnam.

She eventually returned to school, and to the United States, to complete her undergraduate degree in sociology at Temple University in Philadelphia, where she would also earn a master’s degree in counselling psychology. During this time, she began volunteering as a counselor for the local rape crisis center, one of the first in Philadelphia.

In the classroom, my students asked her about what kinds of resources were available for survivors at the time: “Not much,” Colodny replied. “This was ‘72, ‘73, and there were rape kits, but they weren’t everywhere they needed to be. It was mostly peer support. There was nothing built into the system at all…there were some police precincts who were open to training, so that was one of the focuses. But it was the very beginning [of rape crisis centers] in that city so… yeah, it was…” she trailed off briefly, “it made me so angry.”

Working at the rape crisis center was “very hard” and “very painful,” said Colodny. Hearing about “the violence, and the violation,” she remembered feeling “a physical response of wanting to strike back.” “I didn’t do a lot of it,” she clarified, “I was busy with school. But it was meaningful, and I think I helped a little because I had those counselling skills. And I know it helped shape me.”

Similarly, working at a youth diagnostic center in the Philadelphia prison system helped push Colodny to pursue medical school. “If society were equitable,” she explained, “none of the kids should have been there.” They were “just there because of sociology; poverty, disrupted families, poor education, classrooms too large, just structural things that psychotherapy would not do anything for. And I really started thinking I do not want to have a job when I’m done with school, where I administer the state. I refuse to administer the state.”

For Colodny, counselling often meant helping her patients “adjust to a society that is unjust.” Alternatively, “learning to set a kid’s broken bone or catching his failing eyesight before he starts failing in school, all those concrete skills that a physician could have seemed very useful.” Like most women in those days, Colodny had spent her school years discouraged from pursuing math and science, and she credits the feminist movement for empowering her to realize that her reluctance had been shaped by gendered stereotypes.

Laughing, Colodny recalled graduating medical school in 1981 and reciting a modernized version of the Hippocratic oath. Standing next to one of eight women who had been admitted in her cohort, a Black Civil Rights activist and former teacher, “we came to the part about never breaking the law, and she and I just looked at each other, and we shook our heads no, and we didn’t say that part.” Looking back, “I don’t know what I was thinking of,” she reflected, “I just knew I might do some kind of civil disobedience, you know, the Vietnam War, Civil Rights… I wasn’t really thinking of abortion at that time, and I’m sure she was thinking Civil Rights. But I think about that sometimes, it was very,” she paused, “prophetic, or something.”

Raising her young son as a single mother, Colodny struggled to balance the grueling schedule required of medical residents. Nevertheless, she completed her residency in 1983 and established her family practice in Toronto. This is around the same time she became involved with the OCAC. As a medical resident, Colodny attended Dr. Morgentaler’s 1983 trial in Toronto, where she heard a large part of the evidence about the law’s infringement on women’s health and rights. “It impacted me a lot,” she said. “I was appalled. As a physician, as a feminist, I was appalled.”

Though Canada had taken steps to “liberalize” its abortion laws in 1969, these reforms had fallen short of decriminalizing the procedure. Abortions could only be performed in an accredited hospital, and only if that hospital had set up its own therapeutic abortion committee. These committees (usually comprised entirely of men) had to determine that the pregnancy presented significant risk to the woman’s life or health.

Canada’s piecemeal regulations often led to arbitrary decisions and delays. According to Colodny, Canada had the “highest mid-trimester abortion rate” due to delays caused by the therapeutic committee system. Moreover, she explained to my class, “The rate of attempts at self-termination were very high here. There were deaths from bleeding and failed abortion because of women trying to do it themselves. There were so many horror stories from gynecologists at that time of women bleeding out in emergency rooms. These were the circumstances under which criticisms of the law occurred.”

In response to these unjust laws, activists and doctors opened civilly disobedient abortion clinics throughout Quebec and Ontario, beginning with Morgentaler’s Montreal clinic in the early 1970s. With encouragement from Rebick and the OCAC, Colodny followed in Morgentaler’s footsteps and began operating out of the Toronto Morgentaler clinic in 1986.

Beyond the few doctors and medical personnel who willingly risked their licenses to provide essential reproductive health care, Colodny stressed “how important the movement itself was to the eventual success of the repeal of that abortion law. Henry Morgentaler was an amazing, committed ally. No question about it. And he was the ice breaker that made many things possible,” but ultimately, said Colodny, “it’s that social movement that was required to defeat the law.”

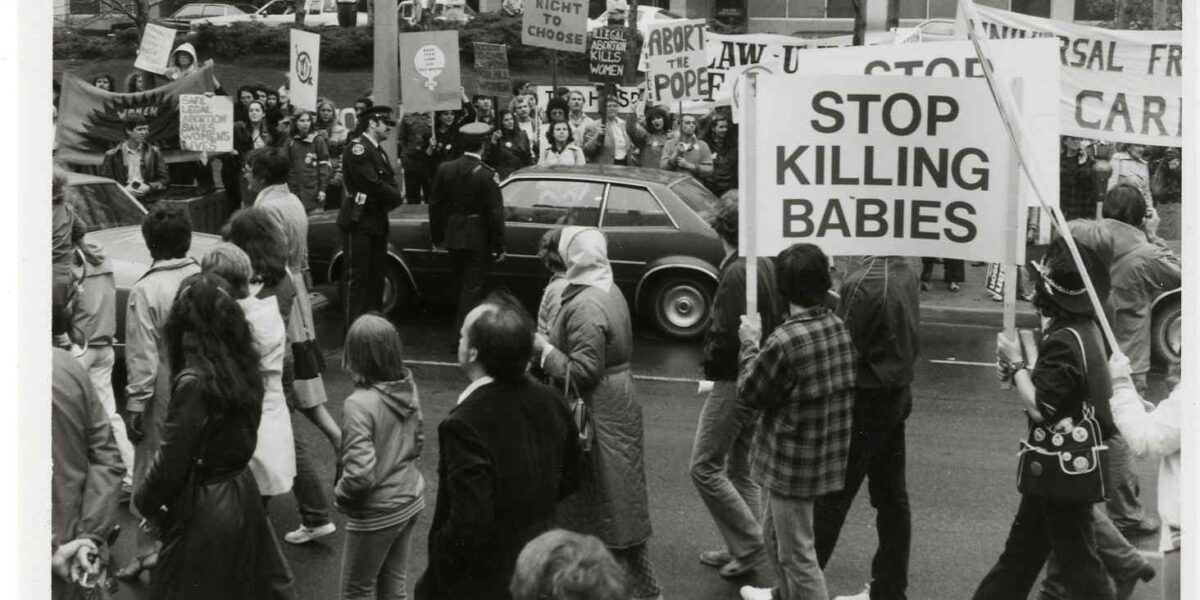

This “movement” included hundreds of pro-choice activists who answered telephones, made referrals, distributed posters, spoke at women’s caucus meetings, marshaled demonstrations, and escorted patients past an ever-present gauntlet of anti-abortion protesters.

“Neither patients nor staff could get into the clinic without walking through them,” Colodny recalled, “they would just hurl threats and insults like, ‘baby killer,’ and ‘we’re gonna get you when you’re not looking’ and ‘we know your son’s school’… It was pretty bad. I didn’t love it.” Though dismissive of their rhetoric, Colodny acknowledged that such tactics were both frightening and insidious: “When you work in a place that has a bomb shelter in the backyard, you know, it affects you. But you try and wall everything off to be there for your patients.” Colodny recalled how anti-abortion protesters once used an acidic substance to burn through the clinic skylight and proceeded to damage medical equipment.

Other tactics included offering doughnuts to clinic patients to delay their procedures (surgical abortion can only be performed if the patient has an empty stomach) and attempting “citizens’ arrests.” In March 1986, Campaign Life Coalition picketed outside Colodny’s home and disrupted her son’s 8th birthday party. “My son is now 45,” she told my class, “But he wanted me to tell you all that it was scary.”

Throughout the late 1980s, abortion clinics were besieged by constant picketing and attacks; the Morgentaler clinic was firebombed twice, and there were bomb threats made against the bus that Colodny rode to Kitchener-Waterloo while establishing a clinic there. “I still have PTSD from that time honestly,” Colodny confessed, “I wouldn’t say it’s a lot now, but somebody calls my name and, you know, I want my back to the wall.”

Despite these challenges, Colodny also had profound experiences of support from the movement and the local community. One day, she remembered, protesters followed her to a restaurant during her lunch break. They hurled epithets at her while she was trying to eat her food. “I finally stood up and I said this woman is really harassing me. I work at the Morgentaler Clinic down the street, can anybody help me?” In response, ten people stood up and put themselves between her and the protesters. “I just felt protected in such an important way,” she said, “It was like riding the crest of a movement. It was really like riding the crest.”

The bravery of OCAC marshals and clinic escorts encouraged Colodny to continue her activist work. Logistical support from friends and her then-partner, Gabe, helped to balance the competing demands of medicine, motherhood, and political activism. She was also supported by local hospital surgeons who agreed to treat her patients if there were any complications. Their services were never required, but their solidarity eased Colodny’s nerves as a newly trained abortion provider.

Throughout her time in OCAC, Colodny travelled across the country to mentor pro-choice activists in civil disobedience and appeared in the media to combat medical misinformation. Civil disobedience, she emphasized, involved coalition-building above all else. While some activists believed they had to find a willing doctor prior to opening a clinic, Colodny claimed, “that’s backwards,” and “they needed support first because if you don’t have the support then there’s no one to protect the doctor.” The mentorship she provided “was more political than medical.” “Make yourself a hive,” she told potential activists, “And if you have the oomph, if there is the hive that will support a clinic, I will find you a doctor… It was less like training,” she clarified, “and more like political propagandizing and strategy.”

Listening to an OCAC tape from 1983, Colodny still finds it difficult to hear women’s emotional stories about their own attempts at self-abortion, botched illegal abortion, and mistreatment from their doctors. “I can barely listen to it, still, I mean, I know that woman,” she said of the voice on the tape, “And, it’s painful. That should never have happened to a person,” but, she continued, “those stories drew people. And by doing that, it not only helped build the movement, but it helped those people to be able to talk about it… you can’t argue a position if you can’t say ‘abortion.’” Abortion tribunals were especially significant for rallying support, Colodny explained, because “They did a lot to anger people,” and created “a community of people who supported never having that happen again.”

Charges against Colodny in September 1986 were dropped in January 1988 when the Supreme Court determined that Canada’s abortion law violated the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Eventually, Colodny returned to the United States with her long-term partner, Joanna, where she continued to provide patients with reproductive health care.

Despite the myriad social and legal reforms which have increased Canadians’ access to abortion over the past four decades, my students expressed concern about the future of their reproductive rights, given the recent fall of Roe v Wade in the United States. “It seems to me that we are really in turmoil,” said Colodny. Although she is “vastly encouraged” by the swift response of grassroots reproductive justice movements, she also worries about rising fascist sentiment in North America.

“I kind of feel like anything could happen. The sense I have now though, is that North American people really feel strongly not just about the right to choose or not wanting a bad law, but they feel like, it’s women’s bodies. The values of bodily autonomy and self-determination are more the norm now. And that gives me hope.”

Finally, I asked Dr. Colodny if she thinks that civil disobedience still has a role to play in the pro-choice movement. “I do,” Colodny responded. “I’m retired on many levels,” she admits, “and I’m not working, I’m not following it as closely as I used to. I try very hard not to have a kind of knee-jerk response … But I just look at all the doctors across the U.S. and I can’t believe how careful they’re being…But” she qualified, “that’s my history, you know? I can’t believe there haven’t been more examples of civil disobedience by physicians. They’re being so careful that they won’t treat a miscarriage, because they might be liable, or they might end up in jail, or they might be charged… it’s a little bit appalling.”

Of course, Colodny remembers the fraught and frightening period in which abortion providers were regularly shot and sometimes even killed by fringe opponents of abortion rights. But she also fundamentally believes in the power of breaking unjust laws. “I never felt like I was committing a crime,” she said emphatically, “the law was the crime.”

Dr. Colodny’s oral histories and her classroom presentation are now available online via the uOttawa Archives and Special Collections database, where you can learn more about the history of pro-choice activism in Canada.