Violence against Indigenous women implicates all people who make their home in today’s “Canada.” According to the Native Women’s Association of Canada’s (NWAC) 2010 report, there are over 600 missing and murdered Indigenous women in “Canada.” Of these deaths, nearly half of the murder cases remain unsolved. NWAC’s report also indicates that Indigenous women are five times more likely to be murdered than other women in Canada. Rates of violence against Indigenous women are highest in British Columbia, with 28 per cent of the cases of missing and murdered women occurring here. Along Highway 16 in Northern British Columbia, a 500-mile section between Prince George and Prince Rupert has been dubbed the “Highway of Tears” due to the series of unsolved deaths and disappearances involving Indigenous women that have taken place along the route. It is unknown how many women have been killed or have suspiciously disappeared on the Highway of Tears, but some estimate the number could be as high as 43. Almost all the victims on the Highway of Tears are Indigenous women. More than half of the women were under the age of 25 when they went missing. A formal RCMP and police response to the murders on the Highway of Tears was not instigated until a young white woman went missing. This highlights how systemic racism creates a context of impunity towards violence against Indigenous women.

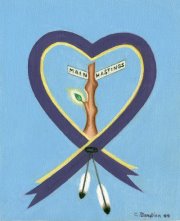

The Memorial March originated 21 years ago in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside. From there, it evolved into an annual event that takes place on or around Valentine’s Day in major centres across “Canada” to call attention to the disproportionately high numbers of missing and murdered Indigenous women from local neighbourhoods. While the statistics vary across these regions, the shared catalyst lies in the disproportionate amount of violence and frequent extreme rights infringements that Indigenous women face across “Canada.” This violence occurs at all levels of colonial society: within university institutions, police, strangers and the family. This march has now come to represent a time for remembering, grieving, honouring and seeking answers for Indigenous communities and their allies.

As visitors on unceded Coast and Straight Salish Territories, we strive to be mindful of local patterns of colonization and resistance and work towards facilitating an organizing process that foregrounds local voices and visions in the planning and implementation of each year’s event. We have learned that this approach necessitates a commitment to long-term relationship-building, which in turn has helped us identify the need for a year-round organizing committee to support this process.

This year, let us walk to honour those who are missing and murdered, and say that today, this violence must stop with us.

Gina Starblanket is Plains Cree and Saulteaux from the Star Blanket Cree Nation on her mother’s side and French and German on her father’s side. She has been part of the organizing committee for the Memorial March in Victoria for the past 3 years and is currently completing a Master’s thesis that emphasizes the need to understand violence against Indigenous women as an issue of Aboriginal, Treaty, and other rights so as to adapt contemporary legal mechanisms to safeguard against their infringement.

Sinéad Charbonneau is mixed-blood, urban, and a member of the Métis Nation. Her family’s traditional territories include areas within the boundaries of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy and the Red River. She has lived most of her life on Lekwungen territories. She has been a part of the organizing group for the Memorial March in Victoria for the past 3 years. She works on a research project about sex workers and their families and is a part of PEERS Victoria and the Vancouver Island Human Rights Coalition.