The call for Occupy May Day emerged out of Oakland, California in mid-February and swiftly gained momentum within the United States and beyond. A people’s movement that took root in encampments across North America last fall — one that was brutally uprooted by coordinated police action — was calling for an American Spring and the day of action it chose was May 1, International Workers Day.

Occupy Wall Street called for a march under the banner: “We are the 99%: Legalize, Unionize, Organize.” Occupy Oakland declared: “The General Strike is back, retooled for an era of deep budget cuts, extreme anti-immigrant racism, and massive predatory financial speculation.” The Occupy May 1st General Strike website has called on “people of the world to take this day away from school and the workplace, so that their absence may make their displeasure with this corrupt system known.”

Across Canada, rumblings are beginning. Just like Occupy movements are finally responding to calls for Decolonization and responsibility to Indigenous nations, relationships are also being made with immigrant rights movements and other anti-racism struggles. Annual May Day demonstrations that have been gaining momentum for years in cities like Toronto and Montreal are now joining forces with Occupy movements.

Chicago and Winnipeg: History of uprisings

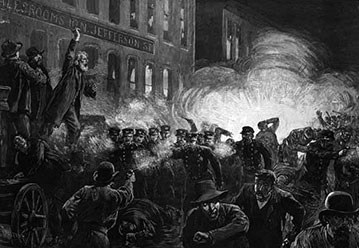

Let’s leap back for a moment. On May 4, 1886, just over 125 years ago, thousands of workers and their families, most of them immigrants from Germany, present day Czech Republic and Slovakia, and other parts of Europe left work and marched through the streets of Chicago to demonstrate for an eight-hour work day.

As James Green, author of Death in the Haymarket notes, this march was not just about workers’ rights. It was a moment of great empowerment for immigrant workers, who were denied the right to vote on the basis of citizenship status; the day became known as “Emancipation Day.” The gathering at Haymarket Square remained peaceful until police arrived demanding the crowd disperse. A bomb explosion led the police to fire on the crowd, killing four unarmed demonstrators. Seven police officers also died, most by friendly fire.

The legacy of Haymarket is one of intense state repression targeted specifically at immigrants in an attempt to break labour organizing. In the immediate aftermath of the Haymarket Massacre, anti-immigrant hysteria was rampant in newspapers. People’s homes were searched without warrants, many were rounded up and eventually eight organizers were indicted — seven of them immigrants — although there was no evidence of their involvement. Albert Parsons, August Spies, George Engel and Adolph Fischer were all hanged. All, except for Parsons, were immigrants. The four become known around the world as the Haymarket Martyrs.

In 1890, in commemoration of this moment, May 1st was declared International Workers’ Day.

Haymarket occurred against the backdrop of displacement and migration across Europe, booming American industrial capitalism, the creation of some of the largest corporations in the U.S. and shifts toward wage freezes advanced by employers wanting to maximize their profits.

In the years preceding Haymarket, workers began to see how imperative it was that they organize themselves as a labour movement. These efforts were led by immigrant workers and community-based groups; often, the organizing was met by extreme levels of police violence, surveillance and infiltration.

The reverberations of Haymarket were felt the world over. This potent mix of migrant displacement and exploitation would incite worker resistance time and again.

Immigrant workers and the Winnipeg General Strike

In Canada some decades later, the Winnipeg General Strike of 1919 shook the country. It demonstrated, yet again, the power of immigrant worker organizing. Threatened by this galvanizing force, the government and the leading media of the day immediately undertook to break workers’ organizing by again targeting immigrants.

In the years preceding the General Strike, anti-immigrant rhetoric dominated the Conspiration Crisis, the Wartime Election Act and the Dominion election of 1917. Dominion security officials were concerned about the possibility of worker unrest and civil disorder in communities with large immigrant populations. Winnipeg was identified as such a community. The government began unrolling racist, anti-immigrant institutional policies, one after the other.

In July 1917, violence erupted between strikers and local police and 23 immigrant strikers were arrested. Most were sent to an internment camp in Cochrane, Ontario and the remainder were charged in Winnipeg courts. But, as Natalia Beszterda notes in her essay documenting immigrant organizing in Winnipeg during those years, “despite these repressive measures, the workers won a limited victory; the construction workers’ union was eventually recognized and working conditions in the industry gradually improved.” In September 1918, the government implemented a series of racist measures intended to stifle migrant-based organizing, including the suppression of foreign language press and the outlawing of a number of socialist and anarchist organizations comprised mostly of immigrants.

The leading Winnipeg newspapers worked in tandem with the Citizens’ Committee of One Thousand — an anti-strike organization created by Winnipeg’s most wealthy and influential manufacturers, bankers and politicians — to whip up anti-immigrant sentiment with the intention of crushing workers’ organizing efforts in the lead up the Winnipeg General Strike. John Dafoe, editor of the Free Press, insisted the best way to undermine the movement was to “clean the aliens out of this community and ship them back to their happy homes in Europe which vomited them forth a decade ago.”

When the Winnipeg General Strike began on May 15 ,1919, the federal government intervened quickly by amending the Immigration Act, ensuring immigrants could be swiftly deported, and by broadening the Criminal Code’s definition of revolution. On June 16, 1919, Royal North West Mounted Police (RNWMP) commanding officers were provided with special authority to execute deportations. The next day, on June 17, four ‘foreigners’ – Michael Charitinoff, Samuel Blumenberg, Moses Almozoff and Oscar Schoppelrie — were amongst the 10 labour leaders arrested in their homes. The four immigrants were incarcerated at Stoney Mountain penitentiary while others were released on bail.

On June 21, 1919, ‘Bloody Saturday’, the RNWMP charged into a crowd of strikers, causing 30 casualties. This police aggression also led to the death of Ukrainian immigrant Mike Sokolowski, who died that day on the steps of Winnipeg City Hall. Over 30 demonstrators were arrested, most of them immigrants. All were denied formal deportation proceedings and, instead, appeared before Winnipeg magistrate Hugh John Macdonald. Macdonald ordered them sent to the internment camp at Kapuskasking and, despite the ardent protests of the defense council appointed by the Winnipeg Trades and Labour Council, all were subsequently deported in secrecy.

The Winnipeg General Strike was a deeply inspiring display of working-class solidarity, of solidarity between citizens and those without status. Within hours of the strike being declared, almost 30,000 workers had left their jobs. The almost unanimous strike action by working men and women, with and without immigration status, closed the city’s factories, debilitated its trade and stopped the trains.

Austerity, precarity and racism

The Haymarket Massacre and the Winnipeg General Strike both happened in economic downturns, neither of which can be compared in size or scale to the 2008 financial meltdown. In June 2010, David Cameron, raised the sceptre of austerity, as a prelude to announcing the U.K. budget.

By June 25-26, when the G8-G20 meetings began in Huntsville, Ontario, the phrase had been firmly entrenched in European politics and formed the backdrop of the G20 declaration. As thousands marched on the streets of Toronto in seven days of organized resistance, facing down police brutality, the age of austerity began anew.

Despite repeated assertions that Canada had survived the financial meltdown of 2008, Canadian austerity policies follow the same pattern as those of the United States, the U.K., Greece, Spain and other countries, giving credence to the widely held belief that austerity policies are just as much ideological as they are economic.

These policies involve massive transfers of wealth: from public services to corporations, prison-builds and the military; from the rest of us to those whose policies and institutions lock us up, make us sick and keep us poor. Policies that slash public services are accompanied by a ratcheting up of repression mechanisms, attacks on the right to strike, and on activists and organizers struggling for a decent livelihood — all of which are embedded in anti-immigrant xenophobia.

Austerity budgets from Ontario and federal governments

On the public sector front, Ontario’s proposed 2012 budget intends to cut $17.7 billion over the next three years and freeze wages for public sector workers. Though the federal government has said that only 19, 200 jobs will be lost in the proposed federal 2012 budget, the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives has calculated that nearly 72,000 jobs will be lost by 2014.

Much of this money is being directly transferred to corporate coffers. Though the Ontario budget puts off new corporate tax cuts, those announced just in the last two years have transferred $2.4 billion to corporations annually. Oil and gas corporations receive an annual $1.4 billion in subsidies from the federal government. Just in 2012-13, corporate tax cuts will amount to $13 billion in lost revenue to Canada.

Part of the austerity measures is the omnibus crime bill, Bill C-10, which will see younger offenders put in to jail for longer. This bill will herald increased RCMP profiling of indigenous communities, profiling which has already resulted in the dramatic over-representation of indigenous populations in federal prisons, with 18 per cent of federal prisoners coming from indigenous communities while indigenous communities make up just 3.75 per cent of the general population. A massive prison build is under way of at least 2,500 new prison cells and the bill will cost Ontario an additional $1 billion. Meanwhile, the Conservatives have passed three anti-labour, back-to-work legislation bills since 2011 against strikers, the most recent being Bill C-33 against Air Canada employees.

Austerity policies have been devastating for people of colour and immigrants. Data from 2010 found that unemployment rates for Canadian-born and established immigrants (in Canada for over five years) were at around 5 per cent at the onset of the recession in November 2008. The jobless rate for newcomers, those in Canada for less than five years, was twice as high at 10 per cent.

By March 2011, a gap had emerged with the established immigrants’ unemployment rate 2 to 2.5 per cent above their Canadian-born counterparts. The jobless rate for recent newcomers shot up to almost 15 per cent. The gap was more pronounced in Greater Toronto, where Canadian-born workers had a 5 per cent unemployment rate in March 2011 — almost 4 per cent lower than the rate for established immigrants and 10 per cent below the level for recent newcomers.

Those immigrants that are working find themselves in precarious, temporary jobs. The wage gap between core working age recent immigrants and the Canadian born rose significantly, from $5.04 per hour in 2008, to $6.30 per hour in 2010. A recent February 2012 Metcalf study found that the number of working poor — people working and earning an income below the low-income median — rose by 42 per cent between 2000 and 2005 in the GTA. Three in four of these are new immigrants. No analysis has been done for data past the 2008 recession, but it is likely that the numbers would paint an even more dreadful picture.

With higher rates of unemployment, lower wages and more precarious employment — immigrants of colour are more reliant on public services. The situation is much worse for those without full immigration status, as many are already unable to access full health care and other essential social services.

A recent study of immigrants and asylum seekers found that in 40 per cent of the cases, people were living in overcrowded situations, had experienced precarious housing or were among the hidden homeless — moving between the homes of their friends and acquaintances, without permanent housing of their own.

At the same time, the criminalization and targeting of immigrants and people of colour is dramatically increasing. A recent Toronto Star analysis of Toronto police stop data from 2008 to mid-2011 shows that the number of young black and brown males aged 15 to 24 documented in each of the city’s 72 patrol zones is greater than the actual number of young men of colour living in those areas.

It is little surprise, then, that immigrants and people of colour are over-represented in prisons and have become more so as these austerity policies have been put into effect.

Part II of this article, coming on the eve of May Day next Monday, will look at immigration policy as austerity and the connection between worker rights and immigrant rights.

Dr Abeer Majeed, Syed Hussan & Mary-Elizabeth Dill are researchers, writers and activists involved in migrant justice, health care, labour rights, feminist and Indigenous sovereignty movements in Toronto.