It’s membership time. Cultivate Canada’s media. Support rabble.ca. Become a member.

“Take up the White Man’s burden –

Have done with childish days –

The lightly proffered laurel,

The easy, ungrudged praise.

Comes now, to search your manhood

Through all the thankless years,

Cold-edged with dear-bought wisdom,

The judgment of your peers!”

-Rudyard Kipling, The White Man’s burden, 1899

The strange case of the Kony 2012 phenomenon is a chance to reflect on the complex relationship between those of us in the so-called First World and those of us in the so-called Third World.

The organization Invisible Children got massive attention for this latest campaign and their intentions may have appeared to many observers as completely benign and admirable at first glance. They were creating global awareness of the atrocities committed by a brutal warlord in eastern Africa and stating that they wanted to see Joseph Kony face justice. It all seemed noble, but on closer inspection and in light of how things turned out, people started questioning the real motives beyond it. One of the results of the campaign was an announcement by the Obama Administration to keep American military advisers in Uganda.

The bizarre naked meltdown of Kony 2012’s main organizer, Jason Russell, in the street in San Diego raised some eyebrows but the most telling incident involving Kony 2012 was when the now famous video was played before an audience in Lira, a town in Uganda where Kony committed some of his worst atrocities. The audience was made up of the very people the Kony 2012 campaign purported to be trying to help yet by the end of the showing the audience became frustrated and lashed out at the members of the organizations, even pelting rocks at them and demanding they leave.

Language and imperialism

What exactly went wrong? Some of the campaign’s critics cite the fact that Joseph Kony is not even present in Uganda anymore and that sending military advisors to Uganada is a completely useless move. A major critique leveled at Kony 2012 by many is the lack of context and the presence of patronizing language. This campaign, many argued, was a new manifestation of the Western Saviour Complex.

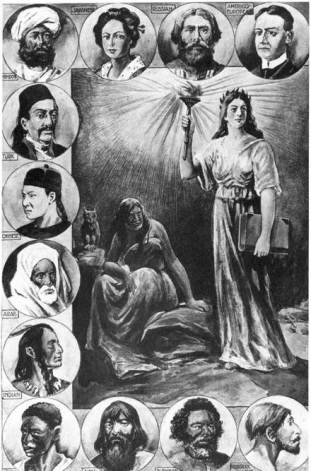

What exactly is the Western Saviour Complex? If I had to come up with a definition for an encyclopedia for it the line would go something like this: the Western Saviour Complex is a deeply embedded notion that any problem in any part of the world can, or even must be solved by Western countries. Historical examples include Columbus bringing Christianity to the “Indians” and America bringing “democracy” to Iraq.

Every colonial project during Europe’s period of colonialism seemed to be justified by some language or another. There were people who spoke out against colonialism in Europe and in the Americas, but ever present was the argument that it was ultimately in the subjected people’s own interest to be governed by outsiders.

Even among liberals one can sometimes sense the language of a perceived natural order involving the Western states playing a role not unlike that of a traditional patriarch. Nowadays these are the voices that claim to be progressive yet they may support international policies that are not so enlightened in the long-run.

In some such opinions Canada’s military presence in Afghanistan is seen as beneficial, or that the ouster of a democratically elected leader in Haiti was necessary for the sake of Haiti’s progress. Others may come from organizations that seem well-meaning at first glance but often carry with them a mentality that view their own selves and their actions as the only solution to people’s complicated problems thousands of miles away. This mentality, whether raw and blatantly obvious or more subtle, is the long-term product of an ideological phenomenon that has its roots in the colonial period of Western Europe.

Let’s start this examination with the role of governments in the international arena. Our first question is: what really guides the actions of most nation-states? The realm of international politics is one where strategy is the most important factor. When nations take actions, whether political, financial or military, they always do so with their strategic interests in mind.

Countries with large economies, and often strong military power to back it up, naturally have the most clout on the global scale. When nation-states like the United States, our struggling global superpower, or rising giants like Russia and China, take actions it is fair to say that the concerns of the respective powers that be in those states are what drive their respective international policies.

In most mainstream media representations, our reasons for moving on that international chessboard are motivated not by the quest for resources or hegemonic influence like other states, but are driven by a desire to do good in the world. This is a Manichean worldview, which is an outlook on the real world as a singular battle of good vs. evil with absolutely nothing in between.

Case study: Iraq

Speaking of a dangerously morally simplistic worldview, let’s discuss a bit on George W. Bush and his legacy. When President Bush II invaded Iraq he cited three major reasons that we are all too familiar with now. The first was to prevent Saddam Hussein, Iraq’s then president, from making ‘Weapons of Mass Destruction.’ That was false.

The second was because the secular Arab nationalist regime of Saddam Hussein was apparently best buddies with Osama bin Laden’s fanatical Wahhabi group Al Qaeda. This one also turned out to be false although it should have been obvious for any one who actually takes time to read up on the very complicated realities of the Middle East.

Finally, the last reason, and the one that Bush and company stuck to until the end, was that the reason for the invasion was for the sake of liberation for the Iraqi people. This line was given to the public repeatedly by the war’s supporters, including the former prime minister of the United Kingdom, Tony Blair, who insisted even after the initial reasons were proven false that removing Saddam Hussein was “the right thing to do.”

It was simply accepted by so many that the war was necessary and was, overall, done in the Iraqi people’s best interest. Liberation from a ruthless dictator, they argued, could only come through war. The Iraqi people could not overcome the tyrant on their own. These arguments seems somewhat strange now in the era of the Arab Spring, when people in the region have successfully (in some cases) removed their dictators themselves.

Can anybody still really believe these arguments for the Iraq War? Do the few supporters left of the 2003 invasion of Iraq by the United States and coalition allies honestly believe that the motivations behind the invasion were based on compassion?

For a clearer answer we have to look past the rhetoric and focus instead on actual actions and results. Look at, for instance, the actions of the United States during the 1991 Gulf War, the first time the United States attacked Iraq. The first President Bush showed an apparent sign of solidarity with Iraq’s people on February 15, 1991, when he told them to “take matters into their own hands and force Saddam Hussein, the dictator, to step aside and then comply with the United Nations’ resolutions and rejoin the family of peace-loving nations.”

After the ceasefire declared on February 24, 1991, and the Iraq government’s brutal repression of the uprising resulting in thousands of Iraqi deaths, President Bush stated on April 2 that he had not “not misled anybody about the intentions of the United States of America.” He went on to say “I don’t think the Shias in the south, those who are unhappy with Saddam Hussein in Baghdad or the Kurds in the north, ever felt that the United States would come to their assistance to overthrow this man. (…) I made clear from the very beginning that it was not an objective of the coalition or the United States to overthrow Saddam Hussein.”

It is especially telling when it is revealed that the initial line of supposed solidarity that went out was really to keep Saddam’s army occupied in Iraq so the United States would run into less opposition from Iraqi troops in Kuwait. The Iraqi people who opposed the government were thus used for strategic purposes and the slaughter was immense in both Iraq’s predominantly Shia South and Kurdish North.

The words are nothing but superficial statements made to justify every action taken by the powerful to convince people that they are always on the side of right in the great simplistic battle of right and wrong.

Actions and actual results speak louder than words ever can. For Iraq, in both 1991 and 2003, the actions belied the words of the western saviours.

Part II of this article will examine the words, actions and results of Canada and other western countries’ interventions in Afghanistan and Libya.

Jesse Zimmerman is a freelance journalist based in Toronto.