Change the conversation, support rabble.ca today.

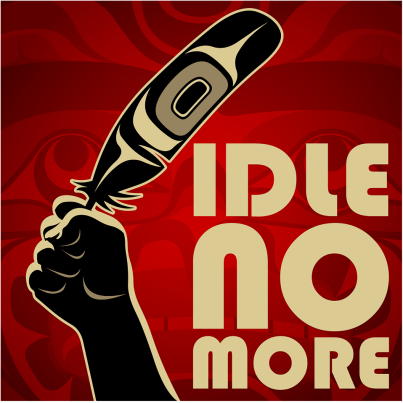

One of the great hazards of journalism is that a writer may come down commandingly on the wrong side of history. The Idle No More movement provides just such an opportunity, for the risk is most pronounced when a marginalized group undertakes to struggle against some social or political orthodoxy. Thankfully, some writers possess a special kind of superhuman resolve which enables them to resist the temptations of prudence and generosity in the face of social change. At least for a while.

Almost inevitably, as the distance between an historic event and the present grows, the journalist will look back with ill-conceived regret at the courageous stance he or she once took against a movement. Perhaps weakened by the passage of time, or crippled by some experience-induced “moral” awakening, these once charmingly cantankerous columnists experience what physicians call “a change of heart”.

No one can know for sure just how long it takes for a journalist to “go soft”. The conservative commentator William F. Buckley Jr. once stood (sorry, wrote) courageously in opposition to the civil rights movement, reserving some of his most heroic denigrating prose for leaders such as Martin Luther King. Two decades later, Ronald Reagan would oppose the creation of Martin Luther King Day because of its economic impact only to sign it in the face of public pressure. But Buckley, still resilient, boldly pointed out the irony of creating a holiday in King’s name given the man’s laziness: “it rankles that we should be asked to take the day off to remember a man whose career was built on leisure.” Yet Buckley, too, would succumb. Fatigued by decades of demeaning the labours of the subjugated, Buckley finally gave in and pronounced his admiration for Martin Luther King. Truly heartbreaking.

If today’s writers have half the tenacity as our friend Buckley, we should see them exhibiting the first signs of quiet approval for Chief Theresa Spence and the Idle No More movement in about ten years. But for the time being we are a truly privileged audience, living in a time when the artful denigration of Indigenous peoples invites us to reflect on those heroes of the past who mocked the words and deeds of blacks, women, and homosexuals. These are truly amazing times.

Consider Terry Glavin’s daring invocation of the macabre as he recoils in horror from the “unspeakably creepy” implications of Chief Spence’s hunger strike. What message could the public possibly get from a woman starving herself to death when so many of her people are also hungry and dying? One can only assume that she and her supporters are oblivious to the symbolism. But Glavin isn’t so stupid. Nor is Christi Blatchford, who valiantly decries the stupidity of fasting as a method of resistance, “There is no end to the stupidity bred by hunger strikes when even friends and family argue that death becomes the person starving.” One can only admire the muscular acumen of those willing to bear witness to the stupidity of sacrifice, or what Blatchford is gutsy enough to brand as “hideous puffery and horse manure.” How unfortunate that those muscles will one day atrophy and yield to the weight of a changing world.

Perhaps it is the stupidity of Indigenous peoples which has engendered such disarray in the Idle No More movement. To that end, Glavin has pointed to Theresa Spence’s “variously contradictory and ambiguous demands” and Andrew Coyne has taken on the movement’s “vast and ill-defined agenda, its vague and shifting demands, its many different self-appointed spokespersons.” Coyne and Glavin follow in the footsteps of those editorial giants who laid bare the imprecise and indefinite nonsense offered up civil rights activists and their leaders. Coyne pushes his intrepid analysis forward, demonstrating that the unclear demands that make Idle No More irrelevant are in fact the product of an internal struggle “between rival factions in the aboriginal community”. Coyne’s perceptive remarks invite us to recall how the disagreement between Malcolm X and Martin Luther King (and the host of other disagreements between black leaders) rendered the plight of blacks incoherent and ultimately irrelevant. Can you even remember what the civil rights movement was about? You can’t because it was so internally diverse.

Still, thanks to the diligence of our reporters, to the stupidity and incoherence of the Idle No More movement we can now add the charge of corruption. As everyone knows, the entire movement has been thoroughly discredited by an objective, non-politically motivated audit conducted by the Federal Governments auditor-of-choice — an audit that exposes Chief Spence’s financial mismanagement of the Attawapiskat reserve. As is clear, the Indigenous rights movement has subsequently unravelled, in much the same way as the Civil Rights movement was disgraced and ultimately discredited in 1960 by the equally objective and non-politically motivated State of Alabama v. ML Kingcase, in which King was charged with inaccurate reporting on his Income Tax. The public was horrified when rumours emerged that the state audit showed King garnering an income of $45,000 in 1958, received on behalf of the Montgomery Improvement Association and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The absurdity of the Civil Rights movement trying to claim legitimacy while one of its leaders mismanage funds was the source of countless equally objective and non-politically motivated editorials.

Sadly, just as those same editorialists would abandon their convictions pertaining to civil rights, with time the follies of Idle No More that are so crystal clear in this moment will lose their grip on our rugged commentators. In a decade or so they will enter a period of moral senility in which their earlier assertions of stupidity, incoherence, and corruption on the part of the Indigenous movement will seem inappropriate, even abhorrent. But for now, absent the ethical burdens of hindsight, we can delight in their mocking disparagement of Indigenous peoples’ expressions of resistance. For Blatchford, it’s those ridiculous “smudging ceremonies, tobacco offerings, the inherent aboriginal love for and superior understanding of the land.” For Glavin, it’s those farcical “trippy references to Mother Earth.” There is little risk to journalists who desire to deprecate new social movements. Likewise, there is little question about who is on the wrong side of history.

Tobold Rollo is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Toronto. He specializes in democratic theory and Canadian politics.