It is by now a common trope: teenagers don’t vote.

On May 2, 2011, the day of Canada’s last federal election, close to 2 million young people avoided the polls. Remarkably, only 37.4 per cent of Canadians aged 18-24 voted.

Since then, much has been made of these historically low numbers, ones which suggest general detachment from, and passivity towards, the political process. After all, the last election featured the third-lowest voter turnout in Canadian history at 61.1 per cent.

What can explain such a pronounced disintegration of youth interest in politics and the aloofness with which young people are supposedly responding to their rights of citizenship?

Could it be that politicians are simply out of touch? Did the policies of past governments alienate youth by failing to represent them in campaigns? Have young people ceased to consider their vote a civic duty? Indeed, there are no simple answers.

One thing is certain, however: young people have a pronounced stake in the continuing health of Canadian democracy. They represent an important electorate which will carry the nation forward in its uncertain future, and cannot be ignored.

***

It follows that, over the past decade, new forms of mass communication such as social media have fundamentally altered the ways in which human beings interact. Websites like Facebook and Twitter now characterize the modern condition. To quote Marx, albeit incongruously, they have torn down spacial barriers, extended our linkages of communication and striven for the “annihilation of space by time.”

The nature of modern Internet technologies have thus gravitated many young people toward the luminescent glow of laptop screens and mobile phones. Issues formerly demanding social action and political participation have been reduced to an expression of 140 characters. The consequence has been, in many cases, an implicitly engrained apathy among youth; the type of passivity engendered by online anonymity and the prevailing assurance that, at one’s fingertips, lie the material and social comforts to bypass unwanted conversation or a vexata quaestio.

But what of the web’s effects on political agency? Has the allure of instantaneous communication through social media actually numbed users into a state of pure indifference? Have Tweets and status updates minimized substantive discussion of issues and the socio-political concerns of the day? Or, more importantly, have these negative assessments been simply premature?

In so far as one considers the Internet a repository for political debate, discussion and resolve, social media certainly assumes a prominent role. And despite the fact only 1 per cent of Facebook users openly declare their political ideology, social networks have statistically proven viable as a means for mobilizing potential voters and precipitating civic duty.

The central question, however, remains: how can the powers of modern mass communication harness the actualization of political agency, and, to what extent have such efforts been successful?

***

To Sean Devlin, site co-founder and executive director of Shit Harper Did (SHD), the Internet has proven a valuable tool for invigorating youth interest in politics. His team includes a number of Canadian Comedy Award-winners, the now-famous Parliament agitator Brigette DePape, and various other activists with the aim of channeling the next generation of ‘creative activists.’

Since its inception, SHD.ca has taken the internet and social media by storm. By allowing users to interact with Canadian politics in a humorous yet meaningful way, it has granted each one of them a participatory role in a movement that is much bigger than the individual.

SHD was launched in April 2011 as an experiment in online activism. Its aims were to stimulate political agency by transcending the ‘attack ad’ or ‘smearing’ strategies of political parties, and inform followers with a systematic breakdown of Harper’s notable environmental cutbacks, anti-union rhetoric, Conservative Party transgressions, and so on.

With the added experience of community organizers, veteran activists, and campaigners, the movement broadened. In March, the team completed a 14-stop national campus tour, conducting workshops and empowering young people with the virtues of civil disobedience.

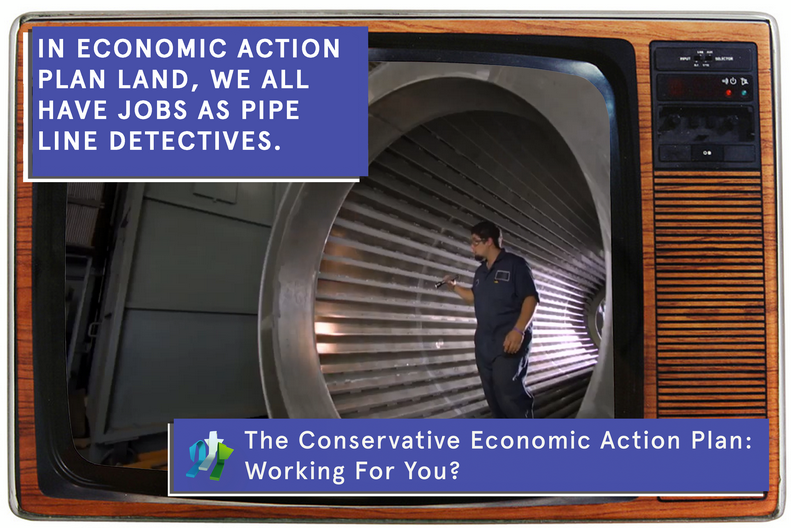

Just two years ago this month, the project was in its infancy. Initiated as a fairly basic webpage with user interaction that included clicking through a laundry list of Harper policies, SHD.ca has been newly relaunched with added multimedia elements including a video series mocking the Conservatives’ inordinate spending on television ads. The SHD team’s humour contrasts with examples of Tory ineptitude to engage viewers and underscore the stark incongruence many young people feel with Conservative policy.

One line from the videos is particularly effective in illustrating the disconnection between Harper’s practices and modern youth (hint: they’re not working): “Every day the Harper Conservatives spend over $215,000 of our tax dollars on advertising that tells us how the awesome the Harper Conservatives are.”

Importantly, SHD communicates with its followers by encouraging conversation about direct action and reiterating the need for change. Described by DePappe as a “shift of culture” in one recent interview, SHD has evolved from a webpage with grassroots ambitions into a catalyst for a shift in both political leadership and the Canadian electoral process. Such discussions, it is hoped, will awaken young people from an undecided and apathetic state of mind to one that is more aware of the intertwined relationship between politics and everyday life.

What is more, by standing in solidarity with youthful protests such as Occupy Wall Street, Idle No More and the Quebec student demonstrations, it too becomes a component of a broader impetus for change borne of historico-political trends working directly against young people.

In what has been called the ‘post-income economy,’ university graduates are suffocated with debt, faced with underemployment and stuck lacking viable outlets for their disparate skills.

Surely, amidst such difficult conditions, movements such as SHD are more necessary than ever. They offer young people a digital camaraderie on which to reply in the fight for our collective futures.

Visit ShitHarperDid and find out how you can develop creative and effective methods of direct action in your own community.

Harrison Samphir is the senior editor at The Uniter, the University of Winnipeg’s weekly urban journal. He hold a B.A. (Hons.) in history from the University of Manitoba. He can be reached at hsamphir[at]gmail[dot]com.

Photo: Part of the national photo-bomb of Harper’s Economic Action Plan ads. (SHD.ca)