Please support our coverage of democratic movements and become a supporting member of rabble.ca.

A new study released this week finds Indigenous children in Canada are more than twice as likely to live in poverty than non-Indigenous children.

The report, co-published by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives and Save the Children Canada, deplores the state of Indigenous child poverty and social welfare across the country.

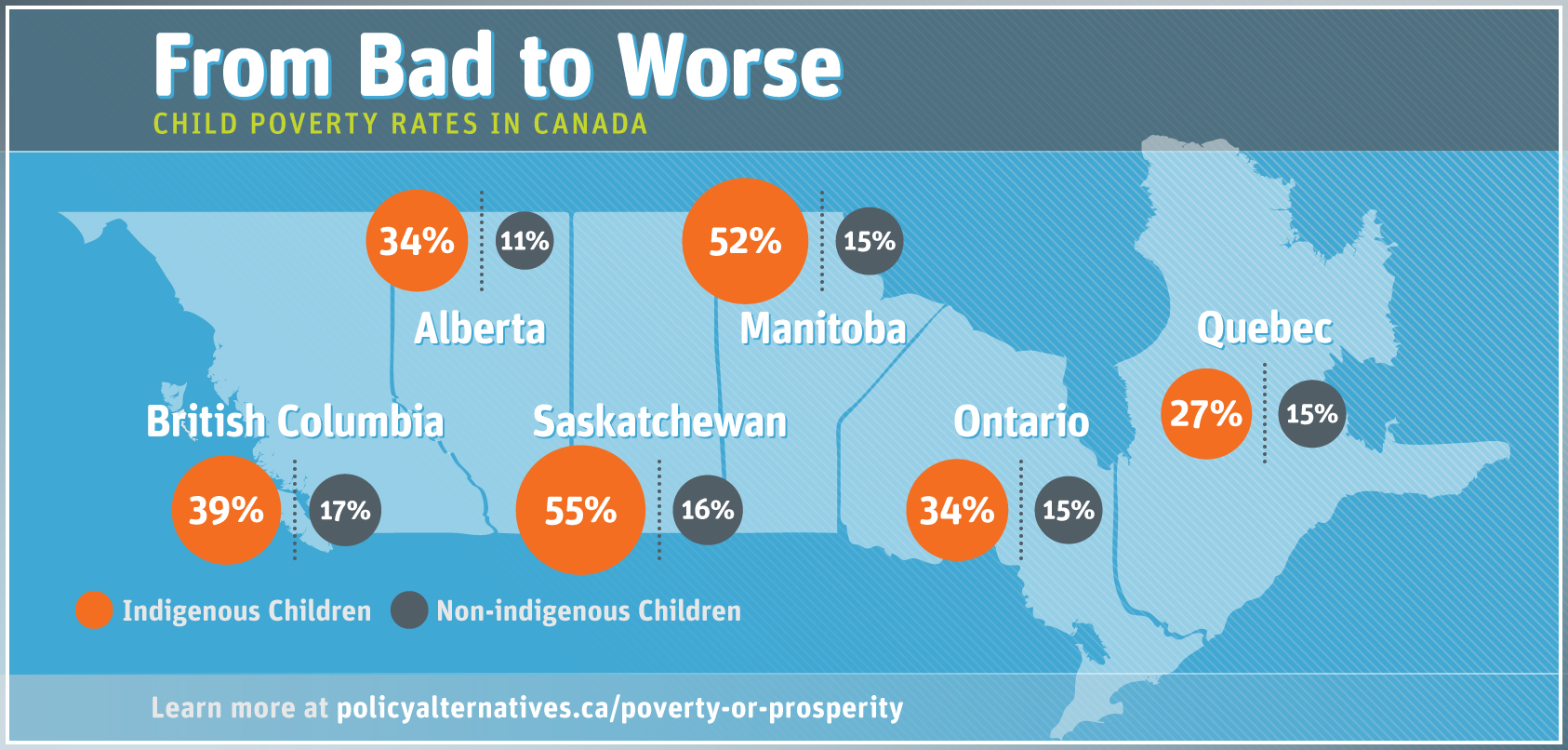

The contrasts in levels of poverty between non-Indigenous and Indigenous children in this country are clear. “The average child poverty rate for all Indigenous children in Canada is 40 per cent, compared to 15 per cent for non-Indigenous children,” says David MacDonald, a Senior Economist with the CCPA and co-author of the study.

This information comes as conditions and social outcomes across reserves are compared to the worst living standards in developing countries. The findings indicate that Indigenous children lag behind in virtually every measure of well being including family income, educational attainment, overcrowding and homelessness, infant mortality, health and suicide.

Aggregating data from the most recent census of 2006, the report delineates three clear tiers of poverty. Status First Nations children have by far the worst poverty rate of any group, at 50 per cent. Métis, Inuit and non-status Indian children have almost half of that at 27 per cent, ranging closer to visible minority children who suffer a 22 per cent poverty rate and immigrant children whose rate is closer to 33 per cent. The poverty rate for children in Canada not from Indigenous, racialized or immigrant backgrounds sits at 12 per cent. The rates are worst across Canada’s prairies, in Manitoba and Saskatchewan, where they are at 62 per cent and 64 per cent respectively.

The difference in poverty levels between status and non-status Indigenous children can, in part, be explained by regional and jurisdictional variations. Non-status children receive social services from provinces, while services for status First Nations and those on reserves falls under the federal government. In most respects, the former fare much better in these findings.

Coupled with these troubling results, and deteriorating conditions across reserves, there is added momentum for the Indigenous population to defend their rights and draw attention to poverty and marginalization.

A report published earlier this year by the McDonald-Laurier Institute warns of potential for a large-scale “uprising” and increasing social friction.

Canada is home to about 1.2 million Indigenous people — a population that is rapidly growing faster than any other demographic group. Significantly, Canada’s performance in addressing child poverty is dire overall — the OECD ranks the country 25th among 30 countries.

“The Indigenous population is the fastest growing in Canada. With adequate and sustained support these people will become an integral part of society and the workforce — particularly as baby boomers retire,” says Daniel Wilson, a former diplomat, Indigenous rights advocate and co-author of the study. “But if we refuse to address the crushing poverty facing Indigenous children, we will ensure the crisis of socioeconomic marginalization and wasted potential will continue.”

Wilson told CBC news that the depth of the poverty is greater than what the data reports: “[First Nations Children] waking up in an overcrowded home that may have asbestos, probably has mould, is likely in need of major repair, that does not have drinking water and they have no school to go to.” (Wilson also contributes a blog to rabble.ca)

Despite the enormous disadvantages faced by Indigenous youth in breaking out of a cycle of poverty, the report indicates that staggering socioeconomic inequality is preventable.

According to the study, $1 billion a year is required from either market income or government transfers to lift all Indigenous children up to the poverty line. Despite this fact, the report indicates that federal transfer payments for social services have increased by merely two per cent since 1996.